BioCycle September 2014

Central America Coffee Growers Generate Biogas

Latin America produces around 70 percent of the world’s coffee. Coffee processing, and in particular the practice of wet method extraction common in Central America, is energy intensive and demands a significant amount of water. The wastewater generated from coffee processing is rich in organic matter and is often discharged untreated into local water sources used by the rural population for drinking water. Aside from water pollution, untreated coffee wastewater also generates methane emissions. To address the situation, UTZ Certified — a program and label for sustainable farming of coffee, cocoa and tea — implemented the Energy from Coffee Wastewater project at a range of differently sized farms in Guatemala, Honduras and Nicaragua (19 pilot sites in total). AD technologies tested included a plastic tubular digester and a prefabricated plastic modular tank. Methane generated was used to run pulping machines, household kitchen stoves and lamps, etc.

UTZ Certified’s “Energy From Coffee Wastewater” project uses AD technology to generate biogas from coffee production wastewater for use in machinery and houselholds in Latin America.

Results achieved during the pilot are summarized in an Executive Summary. (Costs mentioned are approximate and intended as a guide.) For a small-scale wet mill processing between 3,000 to 15,000 lbs of green coffee/ harvest, water used during processing was reduced by an average of 60 to 70 percent. Biogas generated per producer per harvest was 321 m3 and was used for the stove, replacing firewood for four to five months. Average annual operational costs per harvest for the small-scale wet mill are $15/ton of green coffee. Construction costs were $1,000.

California Passes First Statewide Bag Ban

In late August, the California State Senate passed SB 270 to ban single-use plastic grocery bags. Environmental groups and local government advocates overcame fierce lobbying by single-use bag manufacturers to reach this point. The California State Assembly passed the bill the day before the Senate vote. The bill now advances to the Governor’s desk for a signature, according to Californians Against Waste (CAW), a Sacramento-based nonprofit that advocates on behalf of composting and recycling. Governor Brown has until the end of September 30th to take action. “The State Legislature spent a great deal of time debating the merits of this issue over the last several months,” stated Mark Murray, CAW’s Executive Director. “In the end, it was the reports of overwhelming success of this policy at the local level that overcame the political attacks and misinformation from out-of-state plastic bag makers.” The bill was supported by a diverse group of stakeholders, including grocers, retailers, food workers, waste haulers, local governments, and several in-state bag companies.

SB 270 prohibits grocery stores, drugstores and convenience stores from distributing single-use plastic bags, going into effect first in large grocery stores in July 2015. Stores can sell paper, durable reusable bags, and compostable bags with a minimum charge of 10 cents each. The 10-cent charge is to encourage consumers to bring their own reusable bags. The bill also seeks to protect and create green jobs by creating standards and incentives for plastic bag manufacturers to transition to making reusable bags.

Currently, 124 cities and counties in California have adopted a local bag ordinance, covering 35 percent of the population, according to CAW. SB 270 provides a uniform, statewide solution to the rest of the state, modeled after the local ordinances already in place and successfully implemented. “For nearly 10 million Californians, life without plastic grocery bags has been a reality in their communities for at least a year,” added Murray.

Filter Socks And Coastal Resiliency

In June, Filtrexx, manufacturer of socks that are filled with various media for preventing storm water runoff and erosion, sponsored a Student Design Competition at the 14th Annual Meeting of the American Ecological Engineering Society, hosted by Clemson University in Charleston, South Carolina. The theme for both the conference and the competition was “Engineering Resiliency for Coastal Communities.” Filtrexx’s involvement began when Dr. Dan Hitchcock, Associate Professor in Coastal Water Resources, Ecological Engineering, and Vegetative Treatment Systems at Clemson, paid a visit to the beach house of Rod Tyler, founder of Filtrexx. Over the past few years, the coastal property in front of Tyler’s house had been subject to severe erosion as a result of increased storm activity and coastal runoff. Tyler had been experimenting with use of Filtrexx socks to stabilize the sand dunes and prevent erosion. The experiments turned out to be wildly successful, and Hitchcock was sold. The result was a competition for university students from across the country attending the Ecological Engineering conference to try to recreate Tyler’s success with the socks.

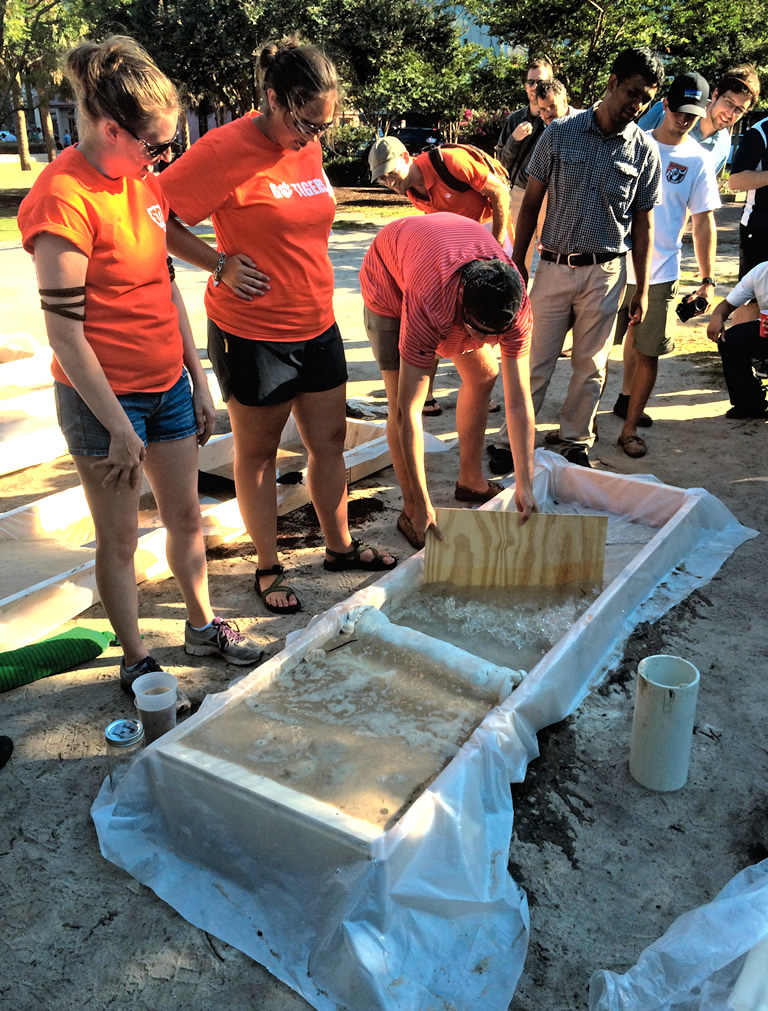

Filtrexx’s Student Design Competition at the 14th Annual Meeting of the American Ecological Engineering Society.

A simulated coastal environment was created in a 4-foot by 8-foot box lined with plastic and filled with 4 inches of water and sand. Eight teams were given Filtrexx socks and a choice of sand, compost and shredded hardwood mulch to either use alone or blend as filter media. They were asked to create a system using the Filtrexx Soxx that would prevent coastal erosion and treat urban storm water runoff for particulates and contaminants. Waves and sediment runoff were simulated for the competition. The designs were judged on their ability to: Minimize sand movement from the “shoreline” in the design box; Optimize permeability and filtration capacity of media for particulate pollutants; and Practicality.

The winning teams, comprised of students form Auburn University, the University of Maryland, Syracuse University, and the State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry, utilized sand as the primary filter media in the socks, the same media Tyler chose at his beach house. “The competition was tricky because when you go to the Filtrexx website, you see examples of socks that use compost to stop sediment,” explains Tyler. “But compost is lighter than sand, so on a beach, this is a bad design principle. By using sand in the sock, you are using Mother Nature against herself. The contained sand is able to dissipate the wave’s energy, thus keeping the sand behind the sock from eroding. Adding some compost to the sand helps increase establishment of vegetation.” When asked about the experience of judging a design competition, Tyler notes, “It was almost like a reality television show. I have never seen such a dynamic, totally engaged group of students working together to solve a problem. Students were running around and realizing they made mistakes, forcing them to shift gears and try something else. It was exactly what we wanted to get out of the competition, so it was really cool.”

Penn State Researcher Tackles Endocrine Disruptors

Endocrine disruptors are excreted by humans from use of pharmaceuticals and personal care products, as well as plastic water bottles. Many of them cause hormone disruption by mimicking estrogen. Conventional wastewater treatment systems were not designed to remove them, so many slip through the system into the water supply when a treatment plant discharges effluent. “Endocrine disruptors are chemicals that disrupt hormone function,” explains Rachel Brennan, Associate Professor of Environmental Engineering and Director of the Advanced Ecological Engineering Systems Lab, or Eco-Machine, at Penn State University, adding that even at very low concentrations, they can cause a variety of effects on aquatic life. “For example, in some streams they are causing feminization — now they’re calling it gender bending — of aquatic species.” Although no one has determined what concentration of endocrine disruptors in water is enough to cause fish feminization, a June 2014 study of small-mouthed male bass in the Chesapeake Bay found a more widespread occurrence of males that had eggs. At one site in Pennsylvania, 100 percent of the fish had become “intersex.”

Some expensive methods to remove endocrine disruptors from wastewater exist, but they are unattainable for most of the world. For the last several years, Brennan and her team have been perfecting use of an economical, unusual agent — the mycelia of white rot fungi — that will destroy the main female hormone in wastewater. Preliminary data demonstrates that the fungi, particularly the Trametes versicolor, or “Turkey Tail” mushroom, can break down 17-beta-estradiol in wastewater, reducing the water’s overall estrogenicity, according to Brennan. She wants to encourage the synergistic activity of mycelia and native bacteria to treat endocrine disruptors as well as other pollutants at the university’s wastewater treatment plant and its Eco-Machine.

“Eco-Machines are designed to treat wastewater to the same standards as conventional wastewater treatment plants, but without as much energy and chemical input,” she explains. “It takes the wastewater in and goes through a series of tanks, but instead of a lot of forced aeration and chemical flocculants, the Eco-Machine uses successively higher forms of life to clean the water, so it behaves like a giant ecosystem. It’s already been shown in the literature that certain fungal mycelia can break down endocrine-disrupting compounds, but nobody’s tried to apply them in wastewater treatment plants or Eco-Machines.”

Brennan and her graduate students secured a three-year, $300,000 grant from the National Science Foundation (NSF) to continue their research. They will conduct a series of batch experiments and continuous-flow bioreactors in the lab, before deploying the technique at the Eco-Machine. “Although the Eco-Machine at Penn State has been treating wastewater continuously since August 2011, we have not yet focused on the removal of endocrine disruptors in that system, due to analytical costs,” she explains. “With this grant, we will be able to investigate the potential of the Eco-Machine to sustainably purify wastewater for communities at low cost.”

Organics Ban Expanded In Vancouver, BC

In late July, the Vancouver City Council (British Columbia) voted to include privately-serviced multiunit residential buildings, institutional, commercial, and industrial (ICI) generators in the city’s plan to divert all organic material from the landfill and transfer stations as of January 1, 2015. For two years, Vancouver has had a diversion program in place for single-family units and some municipally-serviced, multiunit buildings, but in total, that amounted to only one-third of the city’s organic waste. Vancouver has set a goal to reduce waste sent to landfills by 50 percent of 2008 levels by 2020.To meet this goal, the regional government feels that they must include the ICI sector in their organics ban. Although the ban is set to take effect on January 1, 2015, penalties for noncompliance will be phased in, starting with the largest generators first, in July 2015. The penalty will be 50 percent of the tipping fee for garbage loads.