Dan Emerson

BioCycle January 2016

Composting can be a challenge in urban areas, where residents often lack space and options for diverting and recycling food waste. But participating in a program has become easier in the city of Boston, where entrepreneur Andy Brooks has built Bootstrap Compost based in Malden, Massachusetts, into a growing business.

Composting can be a challenge in urban areas, where residents often lack space and options for diverting and recycling food waste. But participating in a program has become easier in the city of Boston, where entrepreneur Andy Brooks has built Bootstrap Compost based in Malden, Massachusetts, into a growing business.

Bootstrap uses two cargo vans and bicycles (seasonally) to collect and transport kitchen scraps from houses, apartments, dorms, co-ops, condos, cafes, offices, and restaurants. Pre and postconsumer vegetative food scraps (no meat or dairy) as well as soiled paper are accepted. Before starting the business on January 1, 2011, Brooks had a longstanding interest in recycling, “although I wasn’t too familiar with it. I started to hear about other mom and pop operations in the area and it occurred to me that Boston would be the perfect environment for a recycling business. It aligns with the progressive nature of the city, which has loads of young people trying to do the best they can do. Composting seemed like an immediate way to make sure your practices are aligned with your belief systems.”

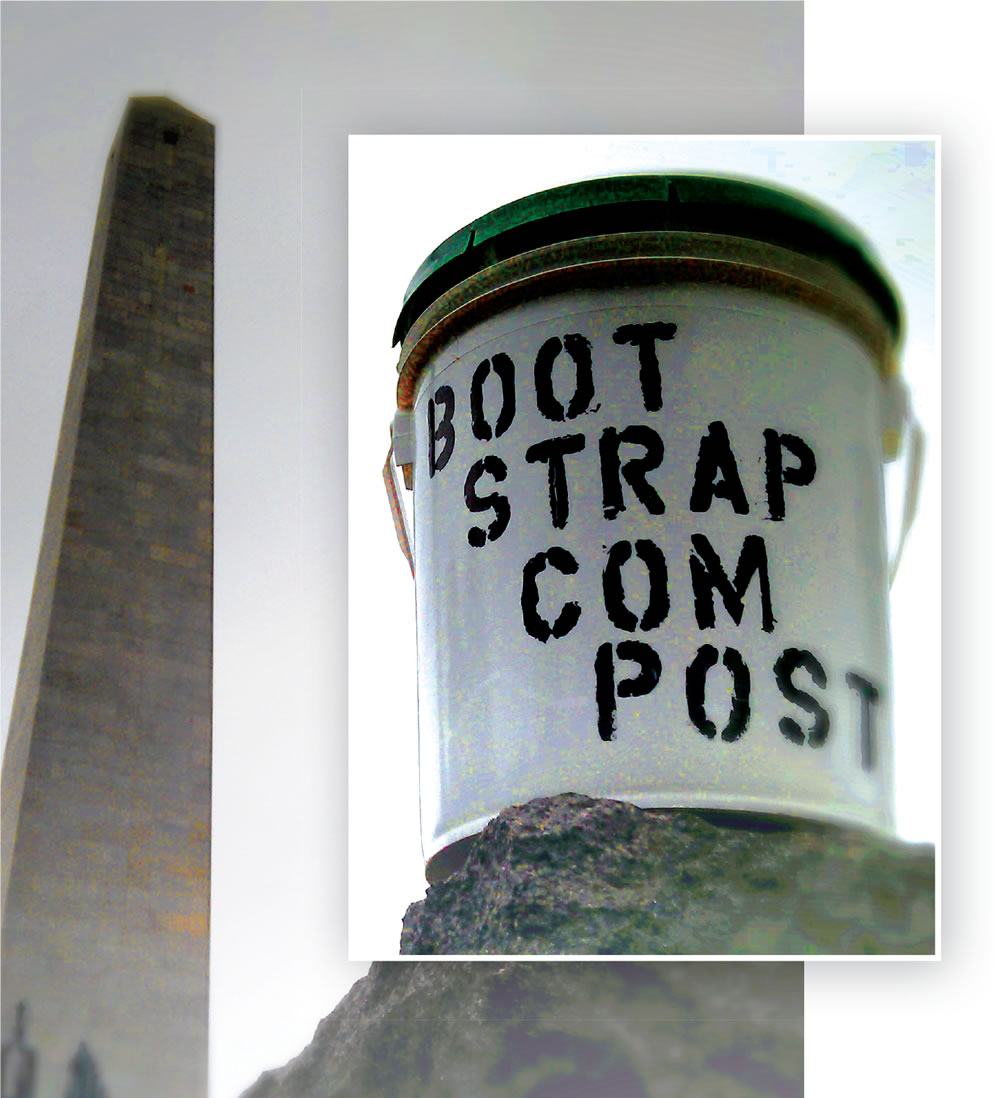

Residential customers collect their food waste in 5-gallon buckets lined with certified compostable plastic bags. The fee is $8/week or $10 for every other week service. Photo courtesy of Bootstrap Compost

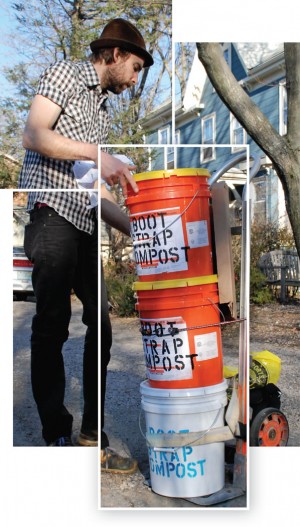

Brooks began by posting fliers about the service and developing a collection route in his Jamaica Plain neighborhood, six miles south of downtown. Bootstrap initially used only bicycles equipped with trailers for collection. Before long, an article in the local Jamaica Plain Gazette led to a Boston Globe feature and “we were off and running,” notes Brooks. Currently, Bootstrap has about 1,500 residential customers, and about 70 commercial accounts. Residential customers collect their food waste in 5-gallon buckets lined with certified compostable plastic bags made by BioBag. The fee is $8/week or $10 for once every two weeks collection. Restaurant and cafe customers use 64-gallon totes with compostable liners. Office buildings and other corporate accounts use metal trash cans. Pick up frequency “depends on how much they are generating,” he adds. Commercial accounts pay weekly fees of $18 to $25, depending on quantity.

Brooks recently moved the business into a 2,800 square foot, leased warehouse, roughly double the size of his previous facility. He has a business partner, Igor Kharitonenkov, who was one of the company’s first customers. Bootstrap uses two cargo vans to pick up food scraps and deliver them for composting to Rocky Hill Farm in Saugus, Massachusetts, about seven miles away. “Over the past five years our use of bicycles has gone from 100 percent to roughly 5 percent — essentially in summer only in the Jamaica Plain neighborhood,” notes Brooks. “We have a substation in Jamaica Plain where the cyclists load and unload and reload the buckets.” The company also provides food waste collection at large events — road races, outdoor fairs, festivals and concerts — and smaller events in the Boston area.

Brooks explains that his primary operational challenge is “ensuring our customers get what they need. If somebody needs an extra bucket or extra collection we can make that happen. We call it ‘premium service.’ Keeping up with customer service is a massive undertaking and component of what we do.”

The state of Massachusetts’ food waste disposal ban took effect in October 2014, covering businesses and institutions that generate at least 1 ton/week of food waste. “This impacts large generators, so it doesn’t directly affect our market,” notes Brooks. “But the ban has had the effect of elevating the consciousness of composting in the community. Municipalities in this area are moving forward with composting.”

Composting Connection

Rocky Hill Farm receives food waste from Bootstrap and other area haulers. It began full-scale food waste composting in 2005, when it started handling source separated organics from Stop & Shop grocery stores in the Boston region. However, composting has been done on the farm since 1983, according to Vice President of Operations Joe Buzun, whose great grandfather started a hog farm on the 50-acre site in 1929.

When the company started in 2011, collection was done exclusively by bicycle and a cargo trailer in the Jamaica Plain neighborhood of Boston. Photo courtesy of Bootstrap Compost

While it no longer receives separated organics from Stop & Shop, Rocky Hill Farm still handles food scraps from various food chains, colleges, a specialty food retailer, and the city of Cambridge (the city had been doing its own residential food scraps collection in some areas of Cambridge, but recently turned the route over to local hauler Save That Stuff). Rocky Hill receives and composts about 75 to 90 tons/week of food and packaging waste, delivered by a handful of local waste haulers. Its tipping fee has stayed the same since 2008 — $60/ton.

Rocky Hill Farm composts food waste, cardboard and leaves; wood chips are sometimes added to the mix as an additional carbon source. In 2008, it upgraded, and expedited, its composting operation by switching from a windrow method to using a “homemade” rotary drum; a second drum digester was added in 2013. The horizontal drums rotate slowly, powered by a 5-horsepower electric motor, and “allow us to process more material, faster,” explains Buzun. The drums each have a capacity of 150 cubic yards, and typically each process about 60 yards of organic material at one time. After about three days in the drums, the material is placed in outdoor aerated static piles, each about 60 to 70 feet long, 8-feet wide and 6-feet high. The windrows are aerated using a perforated PVC pipe system, for about two to three weeks. When finished, the compost is screened to half-inch in size with a trommel screener. Using the rotating drum and aerated static piles, it only takes about five weeks from the initial tip until the compost is ready for screening.

Composting outdoors in the New England winter has posed some challenges, such as frozen conveyors. “When it rains, we’ve learned to keep the mix dryer to compensate for that,” notes Buzun. Adding insulation to the rotary drums has improved their winter-time performance.

Rocky Hill Farm produces about 125 cubic yards per week of finished compost. Most is sold in bulk to area farmers.

Bootstrap Compost’s residential subscribers receive “shares” of finished compost — two 8-pound bags a year — as part of the service. The compost comes from several different sources, including Rocky Hill Farm. “When new customers sign up, they can elect to receive a share or have their share donated to a community garden or school,” explains Brooks. “Right before the holiday, we wrapped up our big winter giveaway, returning 3,500 pounds of compost to our customers. And about half of our subscribers donate their shares.”

Dan Emerson is a Contributing Editor to BioCycle.