New report evaluates why handful of bans and laws that restrict food waste disposal are promising models — and suggests how to strengthen them to increase food recovery and rescue.

Emily Broad Leib, Christina Rice and Jill Mahoney

BioCycle November 2016

Approximately 40 percent of food produced in the U.S. is wasted annually. At a time when millions of Americans are food insecure and thousands of farmers struggle to stay afloat, the negative consequences of wasting food extend far beyond the environmental impacts and loss of resources that could have been otherwise allocated. There are great opportunities for food waste reduction at the federal level, but much can be done by states and localities, whose involvement in finding solutions to food waste and food recovery is vital. In recent years, states and localities have taken many steps to reduce food waste and enhance food recovery by providing state tax incentives to food donors, allocating funding to support food recovery and diversion infrastructure, reevaluating how schools handle food waste, and passing laws that ban organic waste from landfills.

Approximately 40 percent of food produced in the U.S. is wasted annually. At a time when millions of Americans are food insecure and thousands of farmers struggle to stay afloat, the negative consequences of wasting food extend far beyond the environmental impacts and loss of resources that could have been otherwise allocated. There are great opportunities for food waste reduction at the federal level, but much can be done by states and localities, whose involvement in finding solutions to food waste and food recovery is vital. In recent years, states and localities have taken many steps to reduce food waste and enhance food recovery by providing state tax incentives to food donors, allocating funding to support food recovery and diversion infrastructure, reevaluating how schools handle food waste, and passing laws that ban organic waste from landfills.

This article is excerpted from a newly released toolkit from the Harvard Law School Food Law and Policy Clinic (FLPC) titled, “Keeping Food Out of the Landfill: Policy Ideas for States and Localities,” which provides comprehensive information on eight different policy areas that states and localities can consider as they ramp up efforts to reduce food waste. Organic waste (organics) bans and waste recycling laws are one of eight solutions described in the toolkit (see Sidebar for other seven) to keep food waste out of the landfill. In addition to describing existing state and municipal organics bans and waste recycling laws, FLPC discusses why these laws provide promising models for other states and localities, and how they could be implemented and strengthened to increase diversion of food waste from landfills.

Bans & Recycling Laws

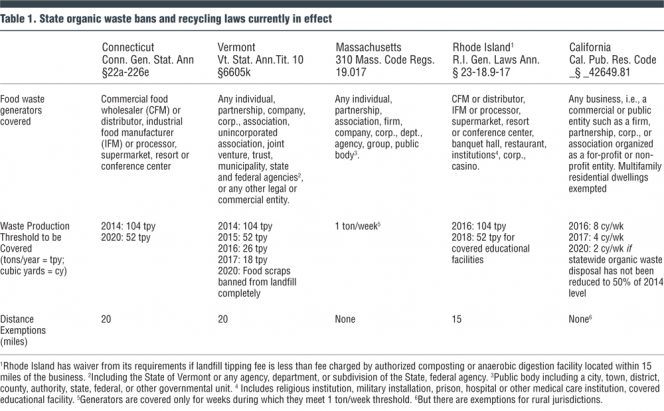

In recent years, five states have implemented state-level waste bans. Some organics bans prohibit certain entities from disposing of organics, including food scraps, in landfills. Other states, and some localities, have implemented mandatory organic waste recycling laws, which require certain producers of organic waste to recycle the organics through specific methods, such as composting.

Organics bans and waste recycling laws are outcome-oriented, rather than process-oriented, which allows businesses or residents to choose how they will prevent food waste or keep food out of the landfill. Both types of laws require “food waste generators” — the businesses, institutions, households, and other entities that create food waste — to reduce their food waste and make sure it is not being sent to a landfill. They both can help encourage food businesses to use their excess food as a resource by diverting it to higher uses. For example, after Vermont implemented an organics ban, the Vermont Food Bank saw food donations increase by 60 percent the following year.

Vermont’s law is the most comprehensive as it is integrated into an overall shift in the state’s solid waste management requirements. Waste bans in other states share many structural similarities with the Vermont law. However, each differs in important details, which in turn has a significant impact on the reach of these laws, and therefore on the amount of food waste diverted from landfills. Areas of difference include:

Types of Generators Covered. As of 2020, Vermont’s law will cover anyone who generates any amount of food waste, including residents. In contrast, the three other states’ bans cover only certain commercial, industrial and institutional entities, with variation among them.

Quantity Threshold. How much waste an otherwise qualifying generator must produce in order to be covered by the law also varies. The laws in Connecticut and Rhode Island only cover generators producing 104 tons of food waste or more per year (although Connecticut’s threshold will decrease to 52 tons/year in 2020), while Massachusetts covers generators that produce one ton/week or more. Vermont’s law began by covering entities generating 104 tons/year but will phase in smaller generators over time, until generators of any amount of food waste are covered in 2020.

Exemptions. Similar variations exist among the laws with regard to exemptions for otherwise-covered generators, for example, based on proximity to a composting facility. While the Massachusetts law does not provide any exemptions for generators based on proximity to a composting facility, Connecticut and Rhode Island cover only generators located within 20 and 15 miles, respectively, of a processing facility that can accept food waste. Currently, Vermont’s law only covers generators located within 20 miles of a certified facility, but in 2020, it becomes a total ban on food scraps in landfills, with no exceptions for distance from a facility.

Unlike the four New England states with organics bans, California’s law takes the form of a mandatory organics recycling law. As of April 2016, businesses in California that generate at least 8 cubic yards (cy)/week of organic waste are required to recycle the organics on-site or subscribe to organics recycling services. The law will phase in businesses that produce at least 4 cy/week in 2017, and if disposal of organics in the state has not been reduced to 50 percent of the disposal level in 2014, the law will phase in businesses that generate at least 2 cy/week in 2020. California’s law does not exempt businesses based on distance from a facility, although it does allow for some exemptions for rural jurisdictions.

At the local level, a number of municipal laws exist that seek to divert food from landfills. Some of these local laws function similarly to the state laws described above. For example, New York City’s organics recycling mandate, which went into effect in July 2016, requires food service establishments in a hotel with 150 or more rooms, food service vendors in arenas or stadiums with seating capacity of at least 15,000 people, food manufacturers with a floor area of at least 25,000 sq. ft., and food wholesalers with a floor area of at least 20,000 sq. ft. to source separate their organic material and either arrange for the transportation of the organics, including food waste, to an appropriate processing facility, or to process the food waste on-site.

Other states and municipalities are actively considering waste bans. New Jersey, for example, has pending legislation that would require restaurants, supermarkets, hospitals, and other food establishments that produce 104 tons/year of food waste and are within 25 miles of an authorized food recycling facility to ship all food scraps to that facility.

Strengthening Bans And Recycling Laws

For states and localities looking to implement an organics ban, the existing state and local laws in other areas may serve as a good starting place. FLPC, in its toolkit, analyzed these laws and identified areas where improvements could keep more food and food scraps out of landfills. Implementing some of the recommendations may be a gradual process, with certain elements phased in over time.

Phase Out Distance Exemptions

Three of the four state-level organics bans currently exempt entities located more than a certain distance, generally 20 miles, from a composting or processing facility. In practice, these exemptions make it so that entities in vast areas of a state do not have to comply with landfill diversion requirements. For example, much of central and eastern Connecticut remains exempt from the requirements of the state’s organics ban because there is no approved facility in those parts of the state.

While it may make sense to include exemptions based on proximity from a processing facility at the outset, phasing out such exemptions over time ensures that many more entities must comply with the law’s requirements, leading to increased food waste diversion from landfills over time. Including language in the enacting legislation or regulations showing that the exemptions will be phased out over time can encourage development of new processing facilities to meet future need.

States might model themselves after Vermont by including a proximity-based exemption at the outset — 20 miles under Vermont’s law — while also setting a date by which all covered generators would be required to comply, regardless of distance (in Vermont, 2020). These states should simultaneously work to encourage development of new facilities through changes to permitting requirements and increased technical support and funding.

Phase In Additional Categories Of Generators

State and local food waste bans can divert larger quantities of material by taking an inclusive approach in defining the types and sizes of generators required to comply with the laws. States looking to implement or improve organics bans should eliminate distinctions based on generator categories, and gradually phase in smaller generators, like individual households, over time. To facilitate compliance by these smaller entities, laws that cover residential and small generators could emulate Vermont by requiring trash haulers and collection facilities that offer trash services to also offer services for organics, including food scraps, by the time residential and/or small generators are phased in.

Eliminate Exemptions Based On Cost Of Composting

Across the U.S., composting can be more cost-effective than landfill disposal because composting facilities often charge a lower tipping fee. Tipping fees at U.S. composting sites average only $36/ton, while the average landfill tipping fee in the U.S. was $44/ton in 2014. However, this may not be the case in all states or regions of the country, and this pricing may change over time.

Rhode Island’s organics ban offers a waiver from the requirements of the law if the tipping fee for the landfill is less than the fee charged by an authorized composting or anaerobic digestion (AD) facility located within 15 miles of the business. It is not clear whether this waiver is having a substantial effect in Rhode Island — the tipping fee at Rhode Island’s only commercial composting site is $30/ton, while the Central Landfill in Johnston, Rhode Island charges a tipping fee of $75/ton. However, the availability of this waiver has the potential to undermine the effectiveness of organics ban laws, particularly if used in a state or locality where privately owned landfills seek to compete with composting facilities. As a result, states and localities should try to avoid exemptions based on the cost of composting relative to landfill costs. States should instead focus on making waste diversion a cost-saving option.

Encourage Multiple Diversion Methods

While generators could find ways to prevent waste or donate surplus to people in need, many of the state and local waste bans focus on composting and AD. Furthermore, waste recycling programs focus almost completely on composting. State and local waste bans or mandatory recycling laws should incorporate the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Food Recovery Hierarchy. This way, even when many of the provisions of the law specifically require or encourage composting, it is clear to covered businesses or residents that there are other steps they can — and should — take to reduce and divert their food waste before relying on composting.

Vermont’s law provides a strong example of how to include language in a waste ban, stating: “It is the policy of the State that food residuals collected under the requirements of this chapter shall be managed according to the following order of priority uses: (1) reduction of the amount generated at the source; (2) diversion for food consumption by humans; (3) diversion for agricultural use, including consumption by animals; (4) composting, land application, and digestion; and (5) energy recovery.”

Several cities in California, including San Francisco and Folsom, provide examples of incorporating such language in the mandatory recycling context. They have implemented educational campaigns that urge residents and businesses to follow the EPA hierarchy, and emphasize the importance of reducing food waste at the source and donating food before resorting to composting.

States and localities can also emphasize the importance of diverting food higher up the hierarchy by incorporating a similar policy into their educational and guidance materials. At the very least, these laws should clarify that food donation is allowed and is a higher priority for wholesome surplus food than composting alternatives. States and localities can also use complementary policy mechanisms, like a tax incentive, to promote food donations.

Optimizing Impact

In addition to FLPC’s recommendations on how to strengthen organics bans and waste recycling laws, its toolkit also includes the following recommendations on steps state and local agencies can take to optimize the impact of bans or laws:

• Provide guidance and education to covered generators

• Facilitate connections between generators and recipients of surplus food

• Provide funding to support the creation of composting and anaerobic digestion

• Encourage small farms to become organics processing sites

• Offer curbside composting programs

• Utilize financial incentives to divert waste

For more details on these recommendations, download the toolkit at http://www.chlpi.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Food-Waste-Toolkit_Oct-2016_smaller.pdf.

Emily Broad Leib is Director, and Christina Rice is a Clinical Fellow at the Harvard Law School Food Law and Policy Clinic (FLPC). Jill Mahoney is a J.D./M.P.H. Candidate at the University of Arizona and Extern at the Harvard Law School FLPC.