A new Pacific Northwest initiative aims to build biological carbon storage to stabilize the world’s heating climate. Recycling carbon from organic residues back to soils is a crucial link.

Patrick Mazza

BioCycle March 2012, Vol. 53, No. 3, p. 45

The Northwest Biocarbon Initiative (NBI) draws together regional climate and conservation groups to advance practices that build carbon in soils and vegetation. A vital thrust is developing economic models that transform organics into carbon-building soil amendments. NBI is led by Climate Solutions, a Northwest advocacy group whose mission is to advance practical global warming solutions.

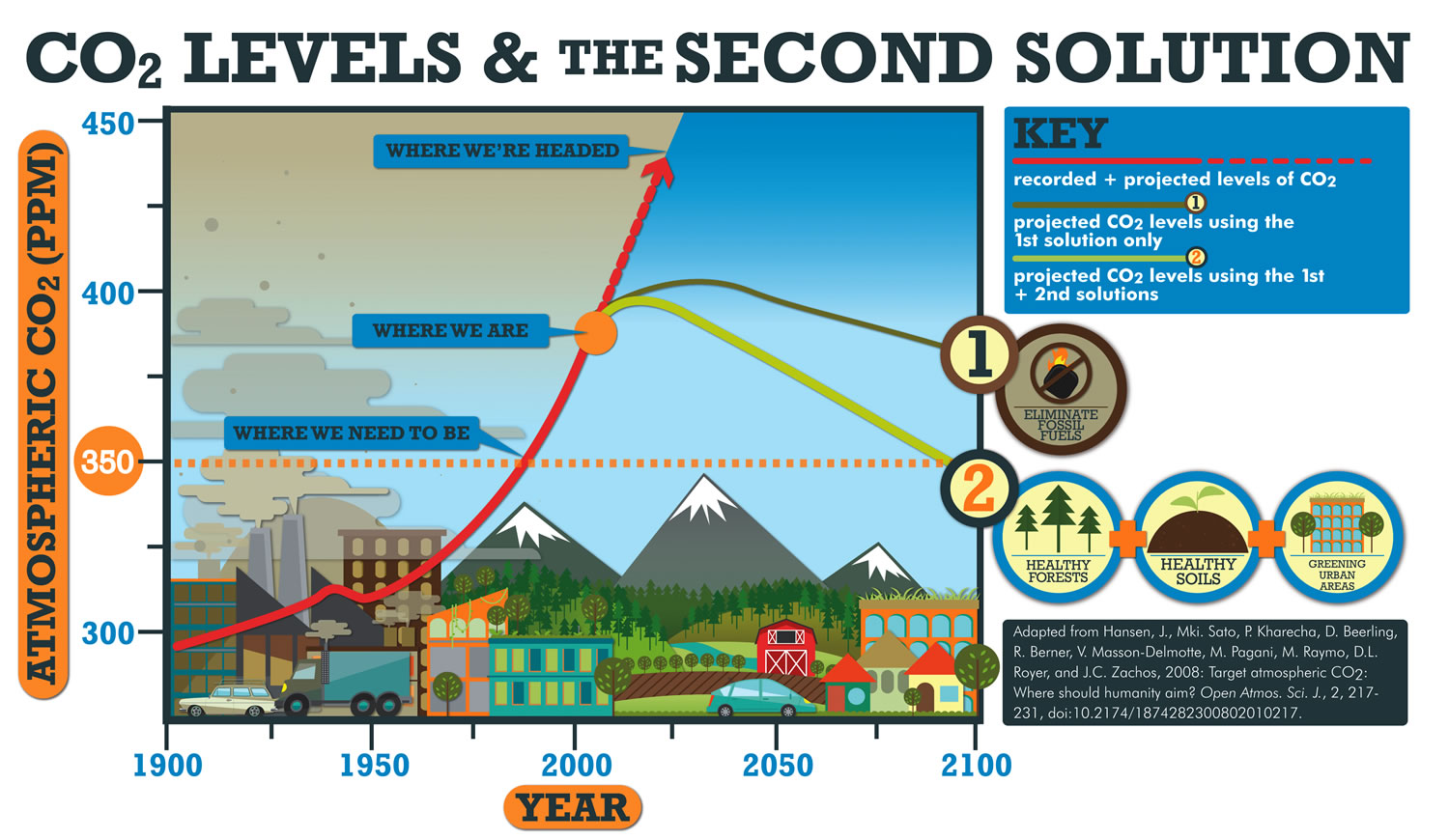

Since 1998, Climate Solutions has focused on replacing fossil fuels with clean energy used efficiently. But a 2008 article by one of the world’s leading climatologists spurred a broader approach. James Hansen of NASA wrote that while reducing carbon emissions is vital, that alone will not halt dangerous climate change. A second solution is needed — active efforts to soak carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere (see Figure). Hansen’s message sounded a clarion call for the climate movement and moved Climate Solutions to develop NBI. The initiative aims to make the Northwest a model for best biocarbon practices.

Scientific Basis

Polar ice core data verifies that atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations remained under 300 parts per million (ppm) for at least 800,000 years. With mass fossil fuel burning since the dawn of the industrial revolution in the 1700s, levels have risen to 392 ppm, and are increasing about 2 ppm annually. A few years ago scientists thought that holding below 450 ppm would avert the most severe climate change impacts. That level was picked because it provides good odds of holding global temperature increases below 2° Celsius, seen as the point where dangerous climate change takes off. But Hansen and other researchers now conclude the threshold to danger was crossed when CO2 accumulation moved beyond 350 ppm at the end of the 1980s.

These scientists build their case on paleoclimate data — how the planet looked in past eras when CO2 concentrations and temperatures were comparable to today’s. One such time is the Eemian, the warm period before the last ice age. It commenced 130,000 years ago and lasted 15,000 more. Using data from ice cores and ocean sediments, Hansen and fellow researchers conclude temperatures then never climbed over 1°C above today’s. That rise, however, was enough to raise oceans 4 to 6 meters over present levels. A 2°C rise would melt ice caps and flood coastal regions where millions now live. “The paleoclimate record reveals a more sensitive climate than thought, even as of a few years ago,” Hansen says. “Limiting human-caused warming to 2°C is not sufficient. It would be a prescription for disaster.”

Hansen and fellow scientists put it bluntly in 2008: “If humanity wishes to preserve a planet similar to that on which civilization developed and to which life on Earth is adapted, paleoclimate evidence and ongoing climate change suggest that CO2 will need to be reduced from its current 385 ppm to at most 350 ppm.”

Regional Response

Biocarbon as a climate solution is not new. It is at the core of carbon offsetting programs that pay to build carbon storage in farm soils and forests. Offsetting fossil fuel emissions is intended to zero out climate impacts. The emerging cap-and-trade system in California will rely heavily on offset markets to meet carbon reduction targets.

Properly structured offsets slow growth of atmospheric carbon. But because they balance current emissions, offsets do not reduce excess carbon accumulated since mass fossil fuel burning began. Reaching 350 ppm requires new policies, tools and business models. New systems must complement rapid displacement of fossil fuel emissions by low-carbon energy and improved efficiency. NBI promotes policies, tools and models that help soak accumulated atmospheric carbon into vegetation and soils.

Climate Solutions brings to this undertaking an unusual background as a group that has long worked on global issues from a regional standpoint. It is a pioneer in efforts to limit carbon emissions and advance clean energy technologies through state and local policies. The group had a hand in creating climate programs such as the Western Climate Initiative and the U.S. Conference of Mayors Climate Commitment, and has helped pass carbon caps and renewable energy standards in Northwest states.

When the 350 ppm challenge emerged, the idea of building regional biocarbon innovation clusters came to the foreground. Climate Solutions cofounder Rhys Roth took lessons learned in previous work to conceptualize a regional biocarbon initiative. That attracted Steve Whitney of Bullitt Foundation, a prime Northwest environmental funder. Whitney heads a program to build market and policy tools supporting ecological services such as water and biodiversity. Practices that enhance the capacity of ecosystems to deliver abundant clean water and wildlife also tend to build biocarbon storage. But climate benefits are often left off the table in advocacy for ecological services and land conservation. Whitney sees biocarbon as a way to broaden the dialogue. “If you don’t shine a spotlight on it, it doesn’t exist,” he says.

The Initiative Forms

Early discussions uncovered a sense that the Northwest is fertile ground for a biocarbon initiative. The region’s forests hold some of Earth’s densest carbon storage. Northwest farms are among the most productive. Advanced conservation programs operate across public and private lands. Cities and states lead in growth management, green infrastructure, recycling and composting. Northwest ecological entrepreneurs are building a new bioeconomy.

The region is also thick with advocacy groups and public agencies advancing all these developments. Could a new initiative add value? Whitney supported Climate Solutions to find out. Over the first six months of 2010, Climate Solutions interviewed around 50 regional leaders spanning farming, forestry, municipalities and entrepreneurs, including advocates, scientists, policymakers and business leaders. Their conclusion was almost uniformly that a region-wide initiative could create a whole greater than the sum of the parts. Research also validated the initial impression that the Northwest has the natural and institutional resources to mount a globally significant biocarbon initiative.

During the initial scoping, Climate Solutions and Bullitt Foundation pulled together an advisory group representing key Northwest conservation groups. Based on the favorable interviews, and with additional support from Wilburforce Foundation, the broader group decided in summer 2010 to launch the Northwest Biocarbon Initiative. With Climate Solutions in the lead, the group now includes the two foundations, American Farmland Trust, Conservation Northwest, Ecotrust, Oregon Environmental Council, Pacific Forest Trust, The Climate Trust and Washington Environmental Council.

NBI is now placing primary focus on communications and networking to promote the “second solution” to climate change. A high priority is creating connective tissue to build community among the region’s diverse biocarbon innovators. The aim is to increase common awareness of the range of activities and identify opportunities for alliances. Over the coming year, NBI will build a regional network of science-policy advisors and innovation partners. Communications in the biocarbon community and to the general public will be facilitated through electronic communications and public events. A website at www.nwbiocarbon.org and a Facebook page at http://www.facebook.com/pages/Northwest-Biocarbon-Initiative/ 278488142169800 link to a regular blog, resources and videos featuring Northwest biocarbon innovators.

The Organics-Biocarbon Connection

One theme NBI will focus on is the vital role organics play in biocarbon accumulation. Soil amendments including manures, compost, biosolids and biochar dramatically increase soil carbon sequestration. This is confirmed by researchers from Washington State University’s (WSU) Climate-Friendly Farming program, one of the region’s key institutional biocarbon resources. For example, one Northwest dryland farming location where municipal biosolids have been applied for 14 years has accumulated carbon at rates as high as 1.4 metric tons CO2-equivalent (MTCO2e) /acre/year. That compares to a 0.1 rate for conservation tillage at a similar location.

Chad Kruger, who directs Climate-Friendly Farming at WSU, says conservation tillage practices such as no-till are vital for preserving soil carbon, but organic amendments are critical for adding carbon. “Increased inputs are far more important than tillage in dictating the carbon balance in soils,” he explains. WSU researchers work with the VanderHaak dairy biodigester in Lynden, Washington. They calculate that codigestion of manures and food waste results in a net reduction of 15.24 MTCO2e annually per cow. Biodigestion “can, in fact, turn a dairy from a net source to net sink for (greenhouse gas) emissions,” researchers write. Kruger notes that installing biodigesters at Washington’s largest 135 dairies could meet 20 to 25 percent of Washington agriculture demand for nitrogen and phosphorous.

Biochar made by pyrolysis of organic matter also has high potential. Jeff Schahczenski, an agriculture expert at the Butte, Montana-based National Center for Appropriate Technology, notes, “… most research to date demonstrates that biochar applied to soil releases carbon back into the environment at a very slow rate that is in excess of several hundreds if not thousands of years.” A WSU study of five different Washington soils found that biochars on all soil types did increase soil C, and the C appears stable.

Targeting Policy And Resources

To stabilize the climate, biocarbon practices will have to be brought to scale. Farmers must move to conservation tillage that minimizes soil disruptions. Forestry must shift from clearcutting every few decades to long-rotation harvest in smaller patches. Municipalities must transition water management from hard pipes and plants to green infrastructure such as wetlands, and more effectively sort organic residues from waste streams. New business models must profitably cycle organic residues from municipalities and industry to farm, forest and urban soils. Scientific research and technology development must be brought to bear in all these sectors.

These advances will require new resources and public policy changes at local, state and federal levels. Making these changes happen is the ultimate aim of NBI. A primary goal targets the eventual return of climate legislation to the U.S. Congress. A portion of revenues from either a carbon tax or carbon auctions should go to support biocarbon practices that reduce atmospheric CO2. This would be distinct from a carbon offsetting system. NBI’s communications and organizing work lays the groundwork for the needed political alliances. The need to deploy a full range of climate change solutions has never been clearer. The world’s nations must phase out fossil fuels, and we must make a new alliance with the biosphere to absorb and store carbon. The Northwest Biocarbon Initiative is building the human and natural alliances that bring biocarbon solutions to scale and pull the planet back from the danger line. In a region that s already fertile turf for biocarbon innovation, the work is growing literally from the ground up.

Patrick Mazza is Research Director for Climate Solutions, Patrick@climatesolutions.org, www.climatesolutions.org