BioCycle July 2013, Vol. 54, No. 7, p. 6

Massachusetts Formally Proposes Commercial Food Waste Ban

The long-anticipated ban on disposal of commercial food waste — along with funding to support anaerobic digestion (AD) — was formally announced on July 10 by officials in the Massachusetts’ Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs (EEA). “Banning commercial food waste and supporting development of AD facilities across the Commonwealth is critical to achieving our aggressive waste disposal reduction goals,” said EEA Secretary Rick Sullivan. “These policies and programs will continue the Patrick Administration’s commitment to growing the clean energy sector in Massachusetts, creating jobs and reducing emissions.” The Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (MassDEP) has proposed a commercial food waste ban (in public comment period now), to take effect by July 1, 2014, that would require any entity that disposes of at least one ton of organic waste per week to donate or repurpose the useable food. Any remaining food waste would be required to be shipped to an AD facility, a composting operation or an animal feed operation. Residential food waste is not included in the ban.

To tap the energy in organic waste, the Patrick Administration has made $3 million in low-interest loans available to private companies building AD facilities. The loans will be administered by BCD Capital through MassDEP’s Recycling Loan Fund, with monies provided by the Department of Energy Resources (DOER). DOER is also making $1 million available in grants for AD to public entities through MassDEP’s Sustainable Materials Recovery Grant Program. MassDEP and DOER have awarded the first AD grant of $100,000 to the Massachusetts Water Resources Agency (MWRA) for its wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) on Deer Island in Boston Harbor. A pilot project will introduce food waste into one of the 12 digester tanks at the WWTP facility to evaluate the effects of codigestion on operations and biogas production. (This DOER funding comes from compliance payments made by electric retail suppliers that have insufficient Renewable Energy Certificates to meet their compliance obligations under the Renewable Portfolio Standard programs.) To ensure that there will be sufficient facilities in Massachusetts to handle the waste resulting from the ban, MassDEP is working with the Massachusetts Division of Capital Asset Management and Maintenance to conduct feasibility studies to build AD facilities on state-owned land. Learn more:

Implementation Realities Of Organics Ban In Massachusetts

The Massachusetts Waste Conundrum

Massachusetts Sets The Table For An Organics Ban

2011 MSW Facts And Figures

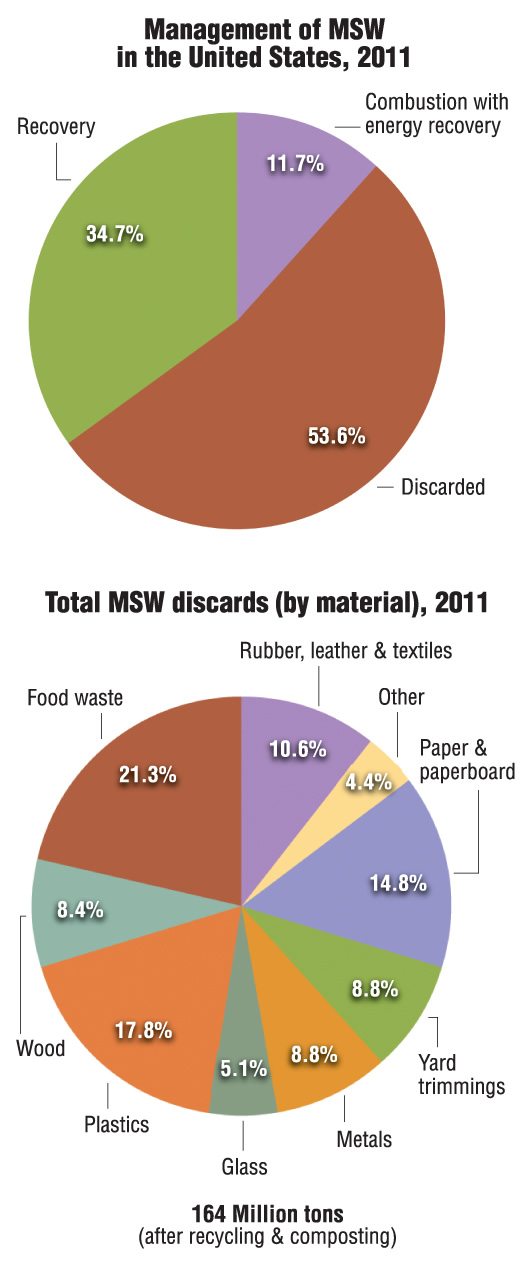

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s annual report, “Municipal Solid Waste Generation, Recycling, and Disposal in the United States: Facts and Figures for 2011,” was released recently. Americans generated about 250 million tons of MSW — 4.40 lbs/person/day. About 66 million tons of the MSW generated were recycled and 20 million tons were composted, equivalent to a 34.7 percent recycling rate. About 163 million tons of MSW were discarded in landfills (53.6%) and 29 million tons were combusted (11.7%). Food waste represents 14.5 percent by weight of all MSW generated but represents the largest (by weight) category of MSW discarded (21.3%). Plastics are the next largest category disposed (17.8%), followed by paper and paperboard (14.8%). Overall, EPA’s data shows little change from the 2010 “Facts and Figures” report, where total MSW generation was 250.5 million tons, 65 million tons were recycled and 20 million tons were composted.

View the EPA fact sheet

Vermont Releases Waste Characterization Study

The Vermont Department of Environmental Conservation (VT DEC) released the findings in May 2013 of a waste composition study of municipal solid waste (MSW) generated within the state. It was conducted at four transfer stations in August and November 2012 (2 each time). The study focused on MSW and Construction and Demolition waste (C&D) from the residential and industrial/commercial/institutional (ICI) sectors delivered to Vermont transfer stations. The data will help guide VT DEC as it begins to implement Act 148, a law passed in 2012 that institutes phased-in landfill disposal bans on recyclables, leaves and yard trimmings and food residuals and requires collection of these materials at the same location where trash is collected. The time periods for sorting were chosen to avoid high yard trimmings generation seasons that could distort the relative magnitude of the various materials sorted. MSW was sorted into 55 primary categories with plastics sorted into a total of 46 subcategories. C&D wastes were visually divided into 8 major categories and 40 subcategories. Aggregate, statewide residential and ICI waste composition is presented in the final report, assuming that the four facilities where sorting occurred are representative of the state as a whole.

The composition of the residential MSW is as follows (percentage by weight): Organics-28%; Paper-22%; Special wastes-21%; Plastic-11%; C&D 10%. Metal, glass and electronics comprise the remaining 8%. Composition of the ICI MSW is as follows (percentage, by weight): Paper-28%; Special wastes-22%; Organics-18%; C&D-15%; Plastic 12%. Metal, glass and electronics comprise the remaining 4%. The special waste category includes textiles/leather, diapers/sanitary products, carpet/padding, batteries, rubber, tires and furniture/bulky items.

View the full report

Connecticut Modifies Organics Diversion Rule

Modifications to Connecticut’s source separated organics diversion rule were signed into law in June. Public Act 13-285, “An Act Concerning Recycling and Jobs,” inserted substitution language in the original rule passed in 2011 that specifies dates for compliance. A primary motivation was to assure developers and operators of composting and anaerobic digestion projects that source separated organic materials would be available for processing if they opened and/or expanded facilities in Connecticut. “On and after January 1, 2014, each commercial food wholesaler or distributor, industrial food manufacturer or processor, supermarket, resort or conference center that is located not more than 20 miles from an authorized source separated organic material composting facility that generates an average projected volume of not less than 104 tons/year of source separated organic material” has to source separate these materials and ensure they are recycled at “any authorized” source separated composting facility with capacity. “On and after January 1, 2020,” all generators listed in the categories above that are located not more than 20 miles from an authorized facility must comply — regardless of how much organic waste they produce. Although the Act’s language doesn’t include anaerobic digesters, they are eligible to receive these source separated organics from the specified generator categories.

Is $300 Billion Recycling Sector Threatened By A Hostile Takeover?

For decades, notes Neil Seldman, president of the Institute for Local Self-Reliance (ILSR), the U.S. recycling movement has fought garbage incinerators that threatened to smother it in its infancy. “Recycling is now a $300 billion industry in large part because of the success of a broad grassroots movement in halting the construction of hundreds of new incinerators,” he explains. But, according to a policy review by ILSR, a “revived incineration industry” is again threatening the recycling industry. “And ironically, this threat is being enabled by the application of new environmental strategy intended to increase reuse and recycling: Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR),” says Seldman. “In British Columbia, for example, the EPR program has embraced the construction of three new incinerators.” EPR requires manufacturers and distributors to take direct responsibility for proper disposal of their products and packaging. “EPR is an important concept,” he continues, “but by putting control of the waste stream in the hands of global corporations it undermines the local network of decision-makers and entrepreneurs that is the reason there is a significant recycling industry. Corporations are driven to lower costs, not to maximize recycling. And this has led, in a growing number of cases, for them to propose incinerators despite their potential impact on local recycling networks.”

ILSR proposes that EPR policies must be subjected to a local economic impact analysis so officials and the public can understand likely outcomes. The policy review identifies positive EPR regulations such as the Illinois e-scrap system that encourages repair and reuse; and poorly designed EPR laws such as the Pennsylvania e-scrap system that actually raises the cost to local governments for handling this material. The report is available at www.ilsr.org/epr-recycling-sector-takeover.

USDA Launches Food Waste Challenge

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), in collaboration with the U.S. EPA, launched the U.S. Food Waste Challenge in June, calling on potential partners across the food chain — including producer groups, processors, manufacturers, retailers, communities and other government agencies — to join in to reduce, recover and recycle food waste. To join the Challenge, participants list the activities they will undertake to help reduce, recover or recycle food waste in their operations in the United States. The Challenge includes a goal of 400 partners by 2015 and 1,000 by 2020. More information about USDA’s initiative is available at www.usda.gov/oce/foodwaste/.