Federal initiatives and local pilot projects are part of an outreach campaign to reduce food waste in U.S. households.

Marsha W. Johnston

BioCycle November 2013

Despite heavy media coverage on TV and in such mainstream publications such as the Washington Post and BloombergBusinessWeek, consumer food waste is not very high on the public radar. “It is an emerging issue,” says Viki Sonntag, behavioral economist and founder of Ecopraxis, and lead researcher on the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Food: Too Good To Waste Toolkit. “People are just becoming aware of its significance and how it aligns with other issues, like climate change and water use.”

Despite heavy media coverage on TV and in such mainstream publications such as the Washington Post and BloombergBusinessWeek, consumer food waste is not very high on the public radar. “It is an emerging issue,” says Viki Sonntag, behavioral economist and founder of Ecopraxis, and lead researcher on the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Food: Too Good To Waste Toolkit. “People are just becoming aware of its significance and how it aligns with other issues, like climate change and water use.”

The U.S. EPA Food: Too Good To Waste pilot projects have households — such as this family participating in the King County, Washington pilot — measure how much food goes

to waste.

Dana Gunders, staff scientist with the Natural Resources Defense Council, was one of the first to put food waste on the public’s radar. Her report, “Wasted: How America Is Losing Up to 40 Percent of Its Food from Farm to Fork to Landfill,” concluded that 40 percent of food in the United States goes uneaten — the equivalent of more than 20 pounds of food per person every month. “Overall, from my perspective, there is a huge amount of momentum on the topic…I feel really optimistic,” notes Gunders, who was a keynote speaker at BioCycle’s West Coast Conference in April 2013. “I think the public has clearly shown they care about this issue…[with] the amount of press that has continued to cover it. Everyone, from established food businesses, to entrepreneurs, to venture capitalists, to nonprofits, is grappling with how to interact and contribute to helping [address] the issue.”

Globally, the depth of the problem is daunting. A new report from the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), “Food Wastage Footprint: Impacts on

Natural Resources,” states that 1.4 billion tons of food per year are wasted, “causing not only major economic losses but also wreaking significant harm on the natural resources that humanity relies upon to feed itself.” The FAO study is the first to analyze the impact on the climate, water and land use, and biodiversity. Among its key findings: Each year, food that is produced but not eaten guzzles up a volume of water equivalent to the annual flow of Russia’s Volga River and is responsible for adding 3.6 billion tons of greenhouse gases to the planet’s atmosphere. Direct economic consequences to producers of food waste (excluding fish and seafood) cost $750 billion annually. Similarly, 1.4 billion hectares (3.5 billion acres) of land — 28 percent of the world’s agricultural area — is used annually to produce food that is lost or wasted.

Gunders is frequently asked which of the multitude of potential food waste topics need to be researched. “We need better information on what households contribute,” she says. “The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) combines household and food service [waste stream information], which renders the information not that helpful.” Elise Golan, Director of the Sustainable Development Office of the USDA’s Chief Economist, acknowledges that the USDA does not have the statistics to allow her to say whether household food waste is the largest contributor. That situation, she says, is due in part to the fact that its food availability statistics, which date back to 1900 for some commodities, were compiled to keep track of food flow, not waste.

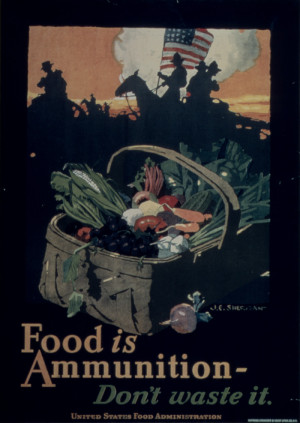

But overall, she adds, the agency has been harping on the topic for a very long time. “The USDA has been urging us to reduce food waste since WWI,” notes Golan. “It has always been on some people’s radar screen, but I think there is an enormous swell of interest in this topic today.” According to USDA, a family of four can save approximately $2,275 a year by making simple changes in how they shop and store food.

Food: Too Good To Waste

In 2011, the U.S. EPA laid the groundwork for an initiative to address household food waste. The agency had been focusing on reduction of food waste in the commercial and institutional sectors via programs such as the Food Recovery Challenge. “We realized that no one was doing anything focused on prevention on the consumer side,” says Ashley Zanolli, who works in the agency’s Region 10 office in Seattle. EPA Regions 9 & 10 convened the West Coast Climate and Materials Management Forum, an EPA-led partnership of western cities and states that develop and share ways to integrate lifecycle materials management policies and practices into climate actions, to address the issue. “It wasn’t just the EPA sitting in a room trying to figure out what local governments would need to reduce household waste, but a collaborative effort across all levels of government,” explains Zanolli, who serves as coleader of the Forum and leads this project.

The resulting initiative was a residential pilot program, Food: Too Good To Waste, which was modeled after the United Kingdom’s Love Food Hate Waste program. “Food: Too Good To Waste” is focused only on source reduction, since preventing food waste in the first place is the best thing you can do environmentally, and for your bottom line,” she says. “We are really trying to move up the food recovery hierarchy to source reduction.”

In 2012, several five-week Food: Too Good To Waste (FTGTW) pilot projects took place in King County Washington, San Benito County, California and Boulder County, Colorado. Sonntag, who began researching sustainable consumption in The Netherlands 10 years ago, was involved in the pilots. She says people consistently “way underestimate” the amount of food that goes to waste in their household. Consequently, the Food: Too Good To Waste planners knew that measuring that waste would be key. “When we began the program, we had a measurement tool to track what was being wasted by volume and weight,” Sonntag explains. “Measuring waste in itself was so powerful in raising awareness..It turns out that the biggest hurdle [to reducing waste] is a lack of awareness of how much food is going to waste, is probably the strongest motivator to reduce waste, once you become aware.”

Zanolli adds that once a consumer’s awareness has been raised, it starts to affect automatic behaviors, such as rote/routine grocery shopping trips. “One of the most novel findings of the pilot was waste aversion,” she notes. “The sense of loss and negative emotion one feels over losing the utility of something, has more impact on behavior than the joy people feel about saving money.” (See below, “The Psychology of Stopping Food Waste”)

The individual households that participated for the full 5 weeks averaged a 25 percent reduction in their food waste. The pilots focused on families with young children and young adults, aged 18 to 30, since research prior to the pilot indicated that they tend to waste the most. Sonntag says one of the most significant demographic barriers to reducing food waste is a dynamic lifestyle. “These are people who don’t even know where they are going to eat for the evening, particularly young adults,” she explains, adding that another challenging demographic is people with a lot of money. “They just buy too much. We all probably buy too much. We have to focus first on buying what we plan to use. Don’t buy more vegetables than you’re going to eat in the following week. If berries are a bargain for 6 pints, take them home and do a little freezing!”

Tool Kit, National Rollout

From the FTGTW pilot projects, tools aimed at enabling other communities to launch their own programs were developed. These include: A research report, implementation guide, shopping list template, produce storage guide (because the pilots found a lack of knowledge among consumers), and posters that tell the story of why food waste is important. The entire toolkit and implementation approach rely on Community-Based Social Marketing (CBSM). Tools were developed for each of the five key waste prevention strategies. For example, making a list with meals in mind is a tool that prompts a strategy to check what a consumer already has before going to the store and only buy what is needed. The tool kit includes an “Eat Me First” refrigerator box that encourages eating up what is about to go past its prime.

Sonntag notes that the tools need to be easily adapted to different communities, since they are using a CBSM approach to program implementation. (CBSM focuses on changing peoples’ behaviors and actions, typically related to sustainability, using a variety of tools such as prompts, incentives, commitments, social norms, and vivid communication.) “We are focusing now on specific tools but also on how to reach enough people in the community to say, `Oh this is an issue that makes a difference,” she says. “We are trying to create a social norm that says food waste is not aligned with our community values. We know that people receiving a message one-on-one are more likely to change behavior, and that certain people in the community are influencers. Part of our effort is to identify communities within communities that will help spread the message.”

In anticipation of launching a national Food: Too Good to Waste consumer program in 2014 in conjunction with the USDA, the EPA is evaluating how to scale up the tools to be part of its Sustainable Food Management focus area. “We are working with communities and business partners around the U.S. to further refine our tools and technical assistance model for Food: Too Good to Waste to help consumers reduce wasted food,” says Zanolli. This includes disseminating the tools to consumers via existing partnership programs with businesses, such as EPA’s Food Recovery Challenge and the U.S. Food Waste Challenge, she adds. Organizations such as the Food Marketing Institute and Grocery Manufacturers Association have also expressed interest in using the toolkit for consumer outreach.

EPA supported pilots in other communities, including Palo Alto, California, and Honolulu, Hawaii, that are using the FTGTW tools and outreach model. And King County, Washington has expanded on tools used in its 2012 pilot program. In partnership with Chef Jackie Freeman and local grocery store PCC Natural Markets, King County has created short online videos that combine food shopping lessons and food waste prevention strategies, as well as an expanded 2013 advertising and media outreach strategy to launch the campaign and drive video views. “Our consultants pitched to the media and TV stations, and our online ads are featured in several locations,” says Karen May, program manager in King County’s solid waste division. “We really wanted to put some energy into a media launch to get the message more prominently exposed.”

King County also launched an enhanced FTGTW website in September that features more online resources and highlights the connections to climate change. “We are interested in keeping food out of the landfill to extend its life, but we are just as interested in climate change, which is the impetus behind this program,” explains May, who notes that both Seattle and King County provide curbside collection of food scraps.

Marsha Johnston is a Washington, DC-based freelance writer and communications consultant, specializing in sustainable development and conservation.