Christine Datz-Romero of the Lower East Side Ecology Center became a New Yorker in 1980. A need for soil to beautify a recycling drop-off site in 1990 led to offering food scraps drop-off and composting. Part IV

BioCycle July 2014

The Lower East Side Ecology Center based in lower Manhattan has been at the forefront of recycling and composting in New York City since the mid-1980s, starting with recycling services and then segueing into composting. As part of BioCycle’s series on community composting in New York City, we interviewed the organization’s cofounder and executive director, Christine Datz-Romero, to shed light on the Center’s beginnings and eventual diversification. Datz-Romero also shared her vision for the future of community composting.

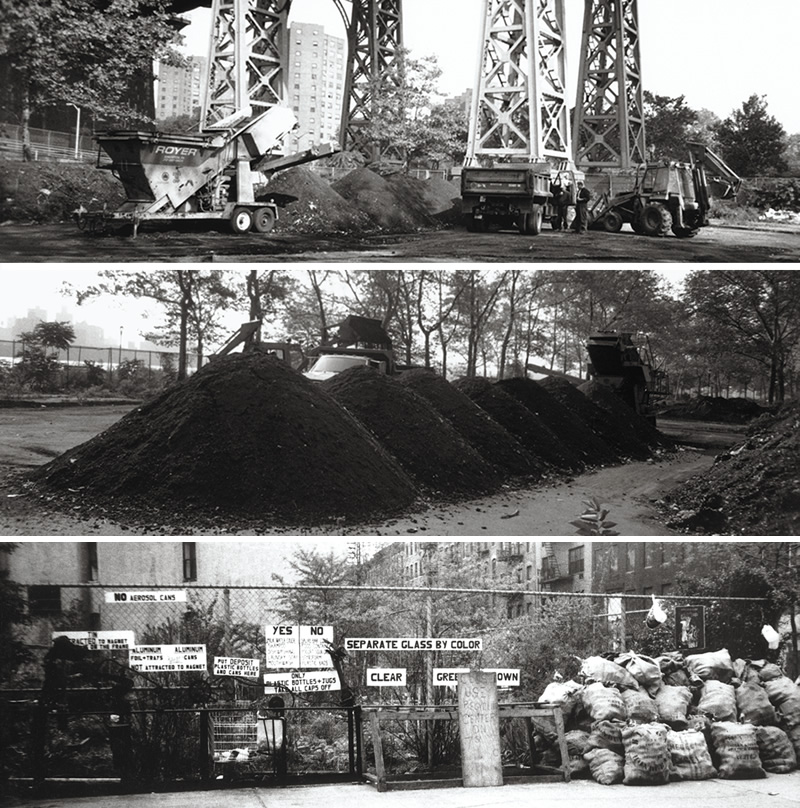

Lower East Side Ecology Center’s original composting site at East River Park in 1998 (top and middle) and its largest recycling drop-off location at 6th Street and Avenue B (bottom).

BioCycle: How was the Lower East Side Ecology Center started?

Datz-Romero: Our founding is, like anything, a personal story. When I moved to New York City from Germany in 1980, I marveled at how dirty and wasteful the city was. It was a culture shock. I was determined to find a group that would accept my recyclables, in particular, newspaper. That group turned out to be the Village Green Recycling Team. I found them by chance, walking around the Village, and immediately began lugging my newspaper, metal and glass to them regularly.

Soon, what started out as a personal interest in finding a place to recycle, quickly grew into something more. I became a volunteer for Village Green Recycling Team, and really enjoyed being part of their initiative. In 1985, I decided to quit my job in a German language bookstore and devote myself full-time to bringing recycling to my neighborhood, the Lower East Side in Manhattan.

My husband, Clyde, and I started a not-for-profit, Outstanding Renewal Enterprises, Inc. (ORE), and were independent contractors for the Environmental Action Coalition (EAC), an organization that coordinated recycling for several New York City (NYC) apartment buildings. EAC worked with superintendents to collect newspaper. We would pick up the bundled newspaper, often times having to climb stairs.

We’d transport the bundles in our step van to Recoverable Resources/Borough Bronx 2000 Inc. (R2B2), which was a buyback center funded by the New York City Department of Sanitation (DSNY). Depending on the market, we would sometimes leave R2B2 feeling very rich, and other times, very poor. Our focus was on amassing newspaper, which had a relatively high value. Glass, by contrast, was about a penny a pound, which made it very difficult, comparatively, to efficiently collect and sell at buyback centers.

BioCycle: Were the EAC buildings your only source of recyclable materials?

Datz-Romero: EAC buildings kept us afloat in terms of revenue generation. We made about $200 per week. However, we really wanted to grow recycling opportunities in our own neighborhood, so we simultaneously set up drop-off sites in front of community gardens on the Lower East Side. Separate containers were set out for newspaper, and metal, glass and plastics. People could deposit materials at any time of day. The EAC routes were run twice a week, and the rest of the week was dedicated to the maintenance and development of ORE’s drop-offs.

BioCycle: What did these drop-off sites look like? Were they staffed?

Datz-Romero: The drop-off sites were not staffed, but we checked them several times a day. The set-up was focused on the commodity and proper source separation. For the collection, we asked a local artist to weld a frame, from which we could hang burlap bags acquired from a local coffee roaster, Porto Rico Importing Co. The frame had a magnet welded on it, so people were able to separate tin from aluminum cans, which had a much higher value. This encouraged people dropping off recyclables to keep the two metals separate without requiring a staff person to instruct them. Glass was sorted by color. We hung a string with a plastic jug attached so that people would know to tie their jug onto the string and not put it in a bag, as those would have taken too much space. For the most part, people separated the materials according to this system. Occasionally, the glass would have to be resorted, but in general, our sites were really well-respected by the community.

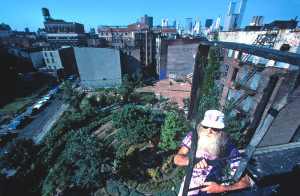

Composting undertaken at 7th Street drop-off center in 1995 to help beautify the 15,000 sq. ft. lot.

The largest and most popular of ORE’s drop-off sites was located at 6th Street and Avenue B. It was always overcrowded, especially on the weekend. So in 1990, we began looking for more space. Eventually, the Department of Citywide Administrative Services (DCAS) rented us a 15,000 square foot lot on 7th Street between Avenues B and C for $150/month. We were thrilled to have this new space.

With a physical location, we needed to find a name. The first choice was the Lower East Side Recycling Center, but we quickly learned that the name “recycling center” triggers specific regulatory requirements, including being located in areas zoned for manufacturing. It was critical, however, that the operation remain in a residential area, where people could easily drop off their materials. So, we settled on Lower East Side Ecology Center.

BioCycle: Why was creating a garden, and eventually a composting operation, at the site so important to your operation?

Datz-Romero: Our aim was to show our neighbors that recycling was desirable and would directly benefit our local community. The best way to do that was to connect ORE’s recycling operation to something that our neighborhood valued: a thriving green open space. At the time, the Lower East Side was a hot bed of community gardens. In the 1970s, many buildings were burned and abandoned and subsequently demolished, creating a lot of empty lots. These lots became eyesores, filling up with illegally dumped garbage. Eventually, the people who lived in the community, including the famous guerrilla gardener Adam Purple (see box), joined together and took responsibility for these lots to create gardens. That is why we have such a great neighborhood today.

Our goal was to beautify the lot, but we weren’t part of GreenThumb, the community garden network managed by the NYC Department of Parks and Recreation. We needed access to necessary resources, particularly soil. So we decided to just make our own soil by collecting kitchen scraps for composting.

Neighbors brought their kitchen scraps to our site on 7th Street. The scraps were mixed with locally-sourced wood chips, manure and wood shavings in a three-bin system, after which the partially-composted material was moved to open piles. We quickly realized that our need for compost significantly outweighed the volume of food scraps being dropped off. At the same time, the composting initiative was having a powerful impact: The Lower East Side Ecology Center (LESEC) was creating soil amendment out of waste that transformed a rubble field into a green oasis, creating tangible impacts that neighbors could really connect to and appreciate.

BioCycle: How did the Center’s role change when New York City initiated curbside recycling service?

Datz-Romero: DSNY began rolling out its curbside recycling program between 1991 and 1993. The program was implemented very slowly, district by district, and the Lower East Side was one of the last communities to be looped in. However, our operation was impacted earlier. As curbside service expanded throughout all five boroughs, buyback centers were no longer necessary. R2B2 closed in 1991, and we had to make special arrangements with DSNY to bring paper, metal, glass and plastic to the MRF in Harlem. By that time, LESEC wasn’t being paid for these materials, but we felt we could not close the drop-off sites until our program participants had curbside service, which wasn’t until 1993.

During this transition, we needed to reorient our focus so that our work would continue to be meaningful. And what would be meaningful? Composting!

BioCycle: Is this when LESEC began its food scraps drop-off at the Union Square Greenmarket?

Datz-Romero: Yes. If LESEC was going to focus on organics and composting, we needed to figure out how to capture greater volumes. One lesson learned by operating our drop-off site at 6th Street and Avenue B is that site visibility is critical to growing participation. The 7th Street site was further east and in a less trafficked area, creating concern about the ability to sufficiently grow participation. We wanted to set up our first food scrap drop-off site in a place where we would interact with a lot of people. The Union Square Greenmarket was a logical choice, particularly because the Village Green Recycling Team had previously offered a Saturday newspaper drop-off there.

In 1994, after successfully pitching the idea to Barry Benepe, Greenmarket’s founder, we opened a drop-off at the Union Square Greenmarket.

BioCycle: How was the drop-off program received by the public/Greenmarket shoppers?

Datz-Romero: I still remember standing at the table that first Saturday, trying to hand out one-gallon buckets, which I had imagined people would eagerly take home to collect their food scraps. Instead the most common reaction was, “Wait, you’re doing what?”

By the end of that day, all of the buckets were given out, but people did not show up the next week with their bins full of kitchen scraps. Nobody came back that first weekend.

But, the program slowly caught on and people brought their materials in neatly tied plastic bags. As kitchen scraps came in, we spent a lot of time figuring out how to balance the needs of our operation with those of the participants and the other farmers at the Greenmarket. How the food scraps were accepted, for example, evolved over time. We had 28-gallon square bins next to our table, and people would drop off kitchen scraps in plastic bags. At first, they could drop the entire plastic bag full of scraps into the bin. Then, once the bin was full, we would empty all the bags ourselves. This initial system was an attempt to minimize the risk of odors, as many of the farmers were concerned that our drop-off site would impact their sales.

It actually took quite some time before we switched to a system of asking people to empty their bags directly into the bin themselves, because staff was not able to handle the volume of bags in the bins. Leachate was not a concern given the and the fact

that most residents dropping off food scraps had kept them in their freezer until they dropped them off.

BioCycle: Was everything collected composted at the Center’s original lot on 7th Street?

Datz-Romero: Yes, but that 15,000 square foot lot didn’t last. Eventually a neighborhood organization raised the money to develop a senior citizen home on part of our site, and by 1996 we knew we had to find a new space to grow the composting operation. LESEC approached the NYC Department of Parks and Recreation about moving to East River Park. We have been there since 1998.

BioCycle: Please describe the composting operation in East River Park?

Datz-Romero: In 1998, Empire State Development Corporation (ESDC) provided LESEC with funding to develop an in-vessel system at our new composting site, and connected us with Jim McNelly from Nature Tech, who designed the system. Jim scaled down a system he had developed using 20-foot sea shipping containers to create a modular in-vessel system using 16 one-cubic-yard plastic bins. After the initial composting in the enclosed system, it was decided to use vermicomposting to cure the materials.

LESEC installed modular in-vessel system using 16 one-cubic yard plastic bins at East River Park in 1998.

Our composting site is a New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (NYSDEC) registered facility. Currently, LESEC composts about 5 tons/week of materials at its roughly half-acre site. Over the past 16 years, the operation has moved several times within East River Park — a testament to its viability. We had to make adaptations out of necessity and availability of on-site resources. For example, when electricity wasn’t available, we switched to a passive aeration system as the bins can be used with either a passive or active aeration system. Overall, we have been impressed with our composting system and its design, and in particular, its ability to collect and manage leachate, which would otherwise be a significant source of odors.

The vermicomposting piece, on the other hand, was not such a success story, mostly because of poor vector control. The semifinished compost used to feed the worms became a food source for local wildlife. In the end, we settled on an open windrow system to cure materials coming out of the in-vessel system but increasing the retention time in the bins before curing to ensure the compost would no longer be attractive to vectors. The windrows are turned weekly to insure vector control.

BioCycle: At what point did LESEC begin its commercial organics composting initiative?

Datz-Romero: ESDC was really interested in having LESEC service New York City businesses. At that time, not a single waste hauler offered collection of source separated organics, and ESDC wanted to help businesses increase recycling. Additionally, a lot of local chefs and restaurant owners who frequented the Greenmarket were interested in composting the organics generated at their businesses.

Given this interest, we saw an opportunity to grow our operation. LESEC purchased a truck with money raised from donations and a low-interest loan from the Institute for Local Self-Reliance. To legally collect commercially-generated waste, we secured a license from the Business Integrity Commission (BIC), the agency that regulates the private waste hauling industry in NYC (see box). Soon, we started collecting from several restaurants and health food stores. Most of these businesses set out their organics in black trash bags, making collection challenging. We had to arrive before the trash and recycling haulers to ensure the separated organics were not thrown on the truck along with other garbage. When we picked up the bags it wasn’t always clear which were source separated organics and which were trash. To avoid potential mix-ups, businesses then kept the materials in their basements, which in turn made collection very time consuming. There also were contamination challenges.

LESEC charged businesses to collect their materials, but we had to stay within the rate caps established by BIC and were competing with haulers that would collect materials curbside in trucks that could hold 20 tons. In the end, this was a money-losing proposition. LESEC maintained the BIC license and we ran the commercial collection service from 1999 until 2004.

BioCycle: There appears to be a growing interest in NYC, and beyond, in starting similar small-scale organics carting operations. Do you have any advice for these groups?

Datz-Romero: My hope is that groups emerging today focus on building business plans that acknowledge each individual piece of the collection and composting process and examine all costs. I see a lot of small-scale operations that are really focused on the collection end, but pay less attention to the processing piece. I also see a lot of operations that are very dependent on volunteers. While these operations are important and exciting, I don’t believe it is sustainable as a business model. It assumes you will always have volunteers. And there are significant costs associated with managing volunteers, and burnout is a real issue.

In addition, there are other costs that need to be better articulated for small-scale haulers and composters. Many of the community-based composters in NYC, including us, have built composting operations on “free,” often city-owned, property. If we had to pay market rent, we could never have done any of this. The scale makes it difficult to sustain sufficient income to cover operating costs without making up for the shortfalls with volunteers, free real estate or some other form of subsidy. I don’t see how you can manage growing volumes of organics in the long run without creating job opportunities for people. I would love to see new groups develop innovative models for collecting and composting organics locally with these constraints and costs in mind.

BioCycle: Because you accept kitchen scraps free of charge, compost sales are an important source of revenue. Are you able to sell all of the compost that you produce?

Datz-Romero: Yes. We sell compost and potting soil at the Union Square Greenmarket, and at our E-waste warehouse in Brooklyn, as well as in other retail settings. We use a rotating drum screener that is loaded with a shovel. Screened compost is put into 30-gallon barrels, which are brought to the Greenmarket where our staff bags materials into one and five pound bags. The larger 20-pound bags we also sell are bagged at the composting facility. The compost is tested annually and meets NYSDEC’s criteria for unrestricted use.

Our challenge is that the demand for compost is a very seasonal business. Everyone wants compost in the springtime, and it can be really tough to meet the surge in demand. Since our operation is outdoors, we are at the mercy of the weather. If we have a wet spring, the compost piles can become too saturated to be screened. We try to screen and bag as much material ahead of time as possible, but storing bags results in another set of issues. Our bag is clear, and if left in the sun, algae begin to grow on it. When that happens, our product is still good, but people won’t buy it. Additionally, if bags of compost are stacked outside and not moved, rats and other vectors will move in and start ripping everything apart.

This article series focuses on the past, present and future of urban community composting of food scraps and other organics diversion in New York City. The series is being written in collaboration with the New York City Department of Sanitation’s Bureau of Waste Prevention, Reuse and Recycling, as well as sister agencies.

BioCycle: What led LESEC to start selling potting soil?

Datz-Romero: We found that a lot of Greenmarket shoppers wanted to buy material from us to transplant their houseplants, but they couldn’t use ‘straight’ compost for that purpose. So we developed a product that includes compost, coconut coir and perlite, and we mineralize it with green sand and black rock phosphate.

Making the potting mix is very labor intensive, but we can charge a relatively high price for it because of the product quality and unique retail opportunity offered by the Union Square Greenmarket. There’s a lovely organic vegetable and herb vendor at the market. After people buy their organic seedlings, they generally come over to us to buy potting soil. It’s a wonderful, mutually beneficial set-up. Our customers are also willing to pay a premium because they realize that purchasing our products supports the program overall.

BioCycle: When did LESEC become a part of DSNY’s NYC Compost Project?

Datz-Romero: Initially, in the 1990s, we had a subcontract through Green Guerillas to develop a demonstration site and signage for the NYC Compost Project, which DSNY created to build public understanding and support for local composting initiatives from the ground up (see “Community Composting In New York City,” November 2013). Then, in 2006, we officially became the Manhattan-based outreach arm of the NYC Compost Project. Becoming part of the project was hugely validating for us. We felt that all of the work we had done in the field of composting was being recognized in a significant way. We are very proud to be a part of the NYC Compost Project and to represent the borough of Manhattan. The NYC Compost Project is a very good program that has helped a lot of New Yorkers, from backyard composters to community organizers, better understand composting and improve community-based operations.

BioCycle: Given your experience with recycling, you would expect a very similar outcome with organics. Do you see the fate of community-based composting in NYC being similar to the story of community-based recycling?

Datz-Romero: DSNY’s curbside recycling program taught us that participation and performance in the program differs radically across NYC’s neighborhoods. Some communities have very high participation, while others do not. We are a city of many different neighborhoods, with many different housing stocks, from high-density dwellings to single family homes. Our recycling literacy is not where we want it to be. Many people don’t even know how to sort newspaper from metal, glass and plastic. When I take my recycling downstairs in my 30-unit apartment building, I spend an extra 10 minutes resorting my neighbors’ materials.

My hope and my vision for rolling out organic waste collection is that we learn from what we’ve seen with curbside recycling: One model will not fit every neighborhood. Curbside organics collection may be viable in communities that have predominantly single-family homes. In denser neighborhoods, where there is no mechanism to effectively monitor who puts what where, we need to be more creative.

I believe that the role of community composters, in addition to raising awareness and building public support for composting, is to create new and innovative models for collecting organic waste. I am really excited to work with my fellow community-based composters to design programs that are most efficient at collecting organics. I think there is a lot of experimenting that we can do.

BioCycle: Can you provide an example of what you consider an innovative model for collecting residential organics?

Datz-Romero: Our Commuter Composting initiative — food scrap drop-off locations at several mass transit stops — is a strong testament to our ability to help build innovative organics collection infrastructure. When we first set up food scrap drop-offs at NYC’s Greenmarkets, we were intentionally seeking to collect residential food waste at a time and place that was a part of people’s daily routine. Commuter Composting is taking that concept a step further. By linking organic waste collection to NYC’s public transportation infrastructure, a critical part of most New Yorkers’ daily lives, we are making our services even more visible and accessible.

Perhaps, most importantly, I believe that all of NYC’s initiatives to divert organics from the waste stream, whether it’s curbside collection or Commuter Composting, should start by focusing on quality rather than quantity. We should not move on to the next neighborhood or next phase of any program without really understanding what contributes to making a program successful or not. We need to fully understand what works and what doesn’t.

Adam Purple, one of the Lower East Side’s most prominent community gardeners, transformed rubble-filled lots into thriving gardens. Photo by Harvey Wang

I think there is still a lot of opportunity for community-based composters, and I really don’t agree that we are going to disappear because curbside collection is being rolled out. We are already playing a significant role in creating programs that are tailored to NYC’s diverse communities, and I hope we will be called upon to do more.