The Kilby family in northeastern Maryland operates a dairy farm, ice cream and milk processing plant, ice cream parlor — and an anaerobic digester.

Stephanie Lansing and Nora Goldstein

BioCycle September 2014

The covered lagoon digester has a capacity of 680,000 gallons. It treats dairy manure in addition to food wastes, such as chicken and meatball fat and ice cream waste.

Kilby Inc., a 600-cow dairy operation located in Colora, Maryland, has the only operational commercial anaerobic digestion (AD) system in the state. In 2009, Kilby Inc. (the dairy farm and milk production business) began construction of a covered lagoon digester, which started operating in March 2011. The digester input consists of flushed cow manure (98% by volume) and food waste (2%), including cranberry waste, chicken fat, meatball fat and ice cream waste. The food waste substrates are added to the digester twice a week. The digester has a capacity of 680,000 gallons and is estimated to produce 50 percent of the farm’s total electricity requirement, powering the milking parlor and ice cream factory. “The digester was actually part of a marketing concept for our milk products,” explains Bill Kilby. “We had been making ice cream and wanted to start processing milk and wanted to have a digester to take those waste streams. Our intention wasn’t to make electricity per se.”

The Kilby family had been dairying in the region for over 100 years. In addition to Kilby, Inc., they own Kilby Cream, a retail ice cream business. Milk is packaged in recycled glass bottles. Electricity produced by the digester’s engine generator helps power the milk processing facility; water can be preheated with heat recovered from the engine. Waste from the milk processing and production facilities is added to the digester.

While the Kilbys evaluated commercially available AD systems, they ultimately decided to design and build the digester themselves, working with the Cecil County (Maryland) Soil Conservation District and the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS). “We ultimately worked with NRCS on two feasibility studies — one before we reached out to digester system companies and one after we decided to proceed on our own,” recalls Kilby. “We had a lot of assistance from the Conservation District and NRCS, as well as the University of Maryland.”

Digested effluent comes down the alleys (1) and washes out sand and manure to a sand lane (2). Sand is scraped out to dry and reused as bedding, and the liquid flows to a settling pond (3) before it is pumped into the digester (top of page). Effluent from the digester flows down to the holding pond (4), and is then pumped back up to the barns to flush the alleys.

Digester Operations

The dairy has a closed loop manure management system. Manure flow is as follows: Digester effluent flushes the manure from the stalls, with some sand, into a sand bedding recovery system. The sand is captured, dried and reused, which greatly increases the sustainability of the farming system (no off-farm bedding materials need to be continually purchased in the form of straw or wood chips). After the sand is trapped, the liquid manure continues to a holding lagoon, where some solids settling occurs before the manure proceeds to the digester. Food wastes are added; retention time in the digester average 10 days. Then the effluent is used to flush the dairy stalls again, and the cycle continues.

The AD system has a single stage biological-chemical hydrogen sulfide scrubber and a 100 kW electricity generation system (EGS) to produce electricity from the biogas. None of the power is put on the grid. “We would have had to pay $28,000 to get hooked into the power line,” notes Kilby.“As it is, we are paying 8 cents/kWh here for electricity. There wasn’t enough money in it to get involved with electricity sales.”

The main technical challenge to digester operations has been the EGS unit and its associated downtime. To increase income from the digestion system, the Kilby Farm would like to upgrade the biogas and compress it, and use the renewable CNG in its vehicle fleet. “We offer home delivery of our sustainable-certified milk, as well as delivery of our ice cream to the Eastern Shore of Maryland for sale in high-end ice cream parlors in St. Michaels among other places,” he adds. “The price of delivery continues to increase. Reducing this cost through use of the biogas is a better long-term investment in relationship to the relatively cheap price of electricity and the complications associated with the biogas engine.”

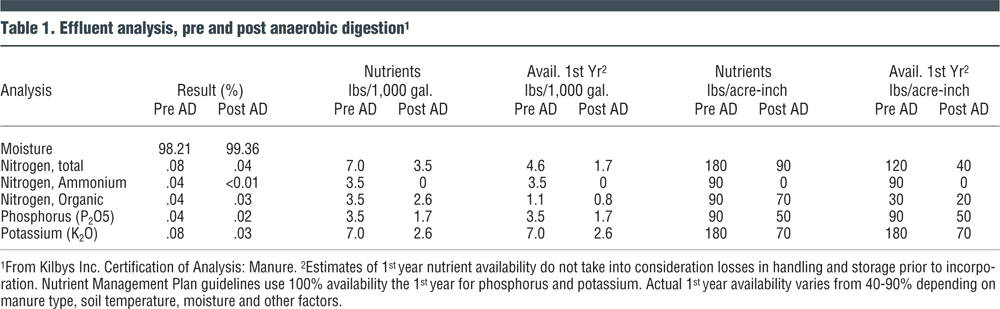

The unique installation of the Kilby farm digestion system has resulted in large reductions in nutrients associated with the dairy operations. By the time effluent has been processed — from sand separation through the digester into the flush recycling pond — the nutrient values have been reduced by half and solids by one percent (Table 1). In addition to the digester, Kilby Inc. has experimented with several innovative nutrient management strategies — most requiring an anaerobic digestion effluent in order to reduce nutrients. These include: 1) Pilot nitrogen and phosphorus separation machine for the digester effluent; 2) Constructed wetland for further nutrient removal from storm water runoff; 3) Strawberries and tomatoes grown hydroponically in a greenhouse using digester effluent after UV and sand treatment; 4) Alternative crop growth for uptake of excess nutrients in digester effluent; and 5) Increased riparian forest area to decrease nutrients leaving the farm and proceeding to the Chesapeake Bay watershed. Water quality studies conducted on the Kilby farm have shown a significant decrease in nutrients as the tributaries move through their fields. The Kilbys are currently participating in a field trial to demonstrate the effect of intensive cropping for the reduction of soil phosphorus.

“A number of our nutrient conservation practices have been based on work from the University of Florida and University of Georgia,” explains Kilby. “We need to encourage our land grant colleges to continue funding more applied research to help with our energy-nutrient opportunities.”

The Kilby family’s stewardship of their farm and related enterprises that have reduced its environmental impact has not gone unrecognized. They were awarded 2011 Cooperator of the Year by the Cecil Soil Conservation District in recognition of their efforts.

Stephanie Lansing is an Assistant Professor of Ecological Engineering in the Environmental Science and Technology Department at the University of Maryland. This article is based on a case history she wrote on the Kilby’s anaerobic digestion system.