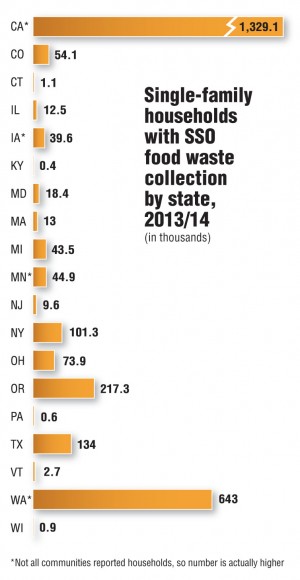

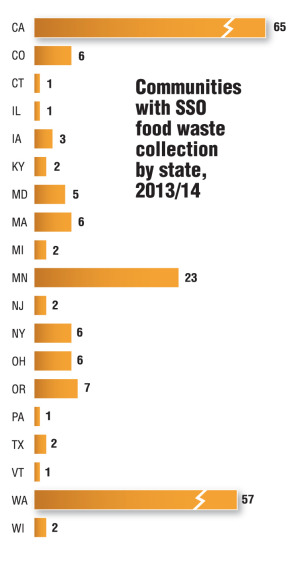

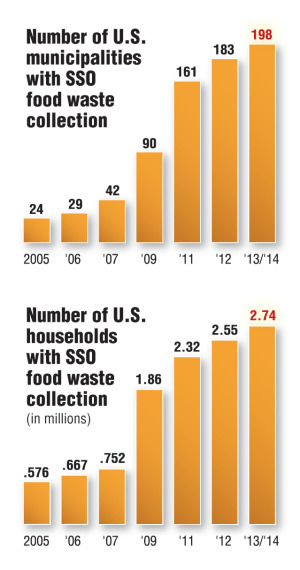

BioCycle identified 198 communities with curbside collection of food scraps, representing 2.74 million households spread out over 19 states. Part II

Rhodes Yepsen

BioCycle January 2015

Interest in residential food waste collection is huge throughout the U.S. That interest is tempered, however, by the economics, logistics and politics in many communities, which can make implementation difficult. In the first part of BioCycle’s Nationwide Survey Report (“Taking States’ Pulse On Residential Food Waste Collection,” October 2014), many of these drivers and barriers were addressed on a state-by-state basis. Part II offers a glimpse into communities that are implementing curbside collection of food scraps.

Number of U.S. municipalities with SSO food waste collection

Number of U.S. households with SSO food waste collection

In all, based on results of a survey conducted in Fall 2014, BioCycle identified 198 communities with curbside collection of food scraps, representing 2.74 million households spread out over 19 states. While this shows steady growth of about 10 percent, the enthusiasm for food scraps collection outstrips the progress shown in that data. Dozens of municipalities have formalized drop-off programs for residential food scraps, and entrepreneurs offer curbside subscription services in communities across the country, some of which have grown quite large (up to 4,000 households!).

New programs in the Midwest and Northeast are tending to use smaller curbside carts to target food waste and soiled paper. This is different from the West, where food scraps are mostly added to existing yard trimmings carts. While both systems are effective, collecting food scraps separately from yard trimmings provides opportunities for hauling and processing efficiencies, especially when yard debris is seasonal. Another difference is that pay as you throw (PAYT) pricing schemes that are widespread in the West are less common in the East, where waste and recycling services are typically paid through property taxes or a fixed fee. While this initially seems like a barrier to incentivizing participation, communities without PAYT are showing extremely high food scraps capture rates.

Several programs in large eastern cities are still in the pilot phase, working on best practices for a given situation. Once proven effective, hopefully there will be a groundswell of activity that matches the growth seen in the West.

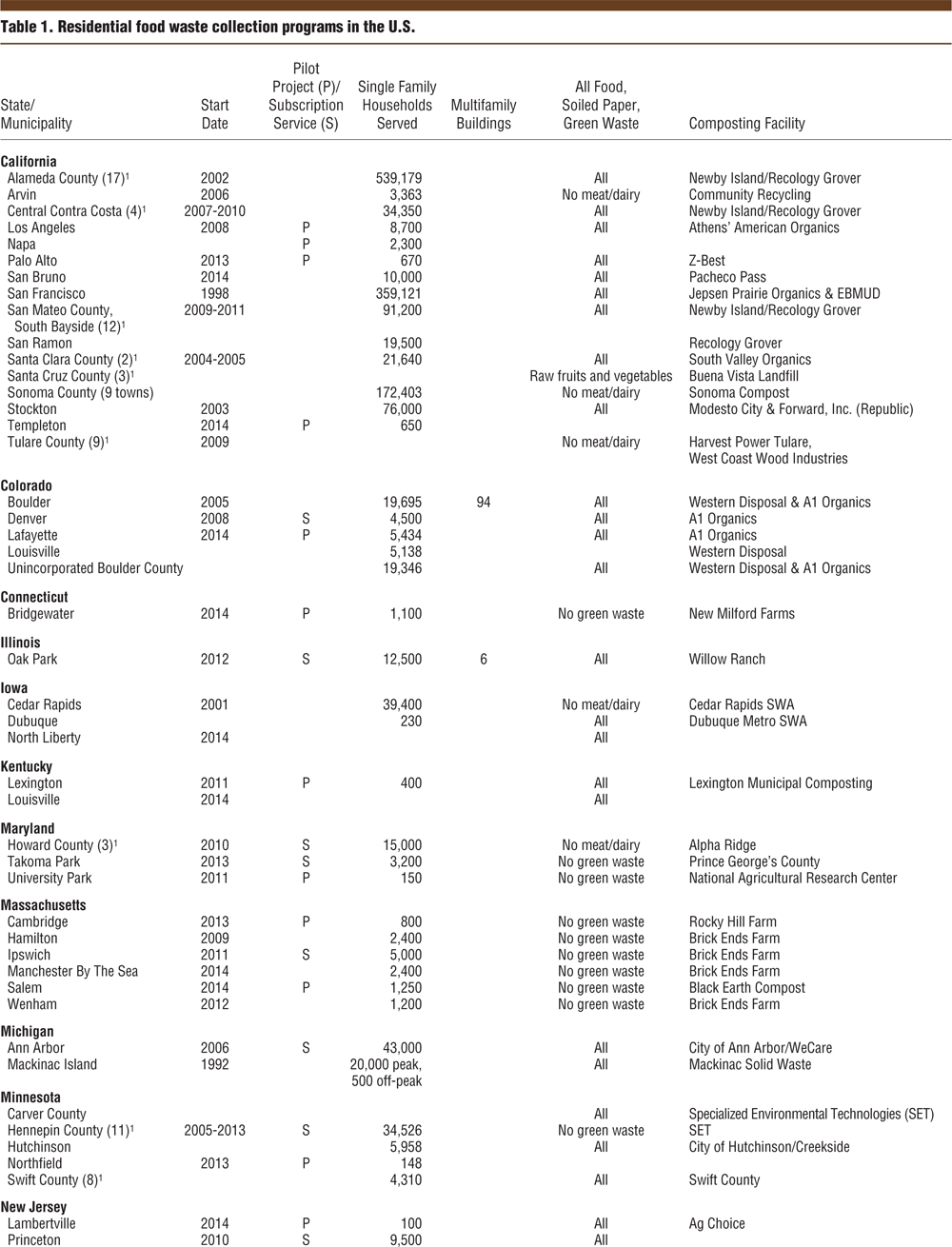

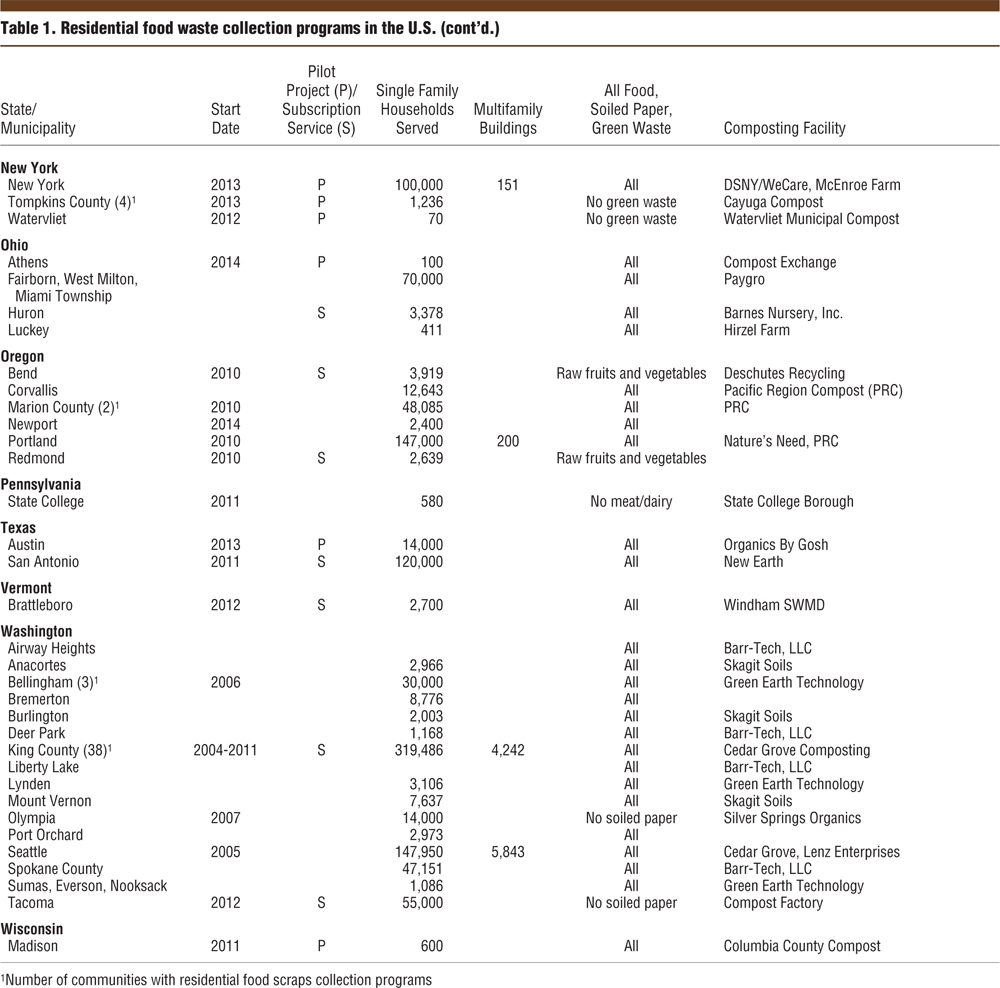

Table 1 provides a state-by-state listing of residential food waste collection programs in the U.S. and the composting facilities where organics are processed.

California

Alameda County: All 420,000 single-family households in Alameda County’s 17 communities have access to curbside residential food scraps collection, with PAYT pricing. Most communities started allowing food scraps in the yard trimmings cart in 2002. StopWaste.org, which oversees Alameda County’s waste reduction, tracks the success of curbside programs by looking at how much “good stuff” (recyclables and organics) are still in the garbage, with a goal of less than 10 percent by 2020. The weighted average of “good stuff” remaining in the garbage for residential programs in 2013 was 31.6 percent.

Alameda County’s Mandatory Recycling Ordinance requires all multifamily buildings (5+ units) to have separate service for paper, OCC, bottles and cans (Phase 1) and for food scraps and compostable paper (Phase 2). So far 12 of 17 communities are complying with Phase 2 (which took effect July 2014, with enforcement to begin January 2015), but 5 of the 12 are on Compliance Schedule Waivers, whereby multifamily organics have been delayed for a specified period of time.

Central Contra Costa: Four jurisdictions in the Central Contra Costa Solid Waste Authority (CCCSWA) allow food scraps in the yard trimmings cart, representing about 62,500 households. In 2015, CCCSWA will expand food scraps collection to the unincorporated areas and the towns of Danville, Blackhawk, Alamo and Diablo. All food scraps are permitted, collected weekly and composted at either Newby Island or Recology Grover.

Los Angeles: The City of Los Angeles continues to offer a limited food scraps collection pilot, started in 2008, to 8,700 households. In July 2014, the nonprofit Global Green USA and hauler/composter Athens Services introduced food scraps collection to a large multifamily building in the Lincoln Heights neighborhood.

Palo Alto & Santa Clara County: In Santa Clara County, the communities of Gilroy and Morgan Hill have been collecting residential food scraps since 2004 and 2005 (respectively). Palo Alto, also in the county, piloted a wet/dry residential program in 2013 for about 670 single-family households and 80 multi-unit households. For the pilot, food scraps had to be bagged (in Biodegradable Products Institute (BPI) certified compostable bags) and placed in the yard trimmings cart. The collected material was then sorted at a MRF, with food scraps composted a Z-Best in Gilroy. The pilot was very successful, but the city has decided against the two-cart system for several reasons (e.g., devaluing of the recyclables), and instead plans to roll out a three-cart system in July 2015 to all 18,000 single-family homes (pending City Council approval). Sunnyvale, another town in Santa Clara County, plans to launch a food scraps collection pilot for 500 households in February 2015.

San Mateo County: San Mateo County has 13 communities with residential food scraps collection, 12 in South Bayside Waste Management Authority’s (WMA) district, plus San Bruno. San Carlos was the first to come online in 2009, with the rest of South Bayside WMA following in 2011 and San Bruno in 2014. All communities have PAYT, and many have a wide range of cart sizes (20-96 gallons). South Bayside WMA collected 66,500 tons of organics in 2014 (Jan.-Nov.) from roughly 93,000 single-family homes, plus another 20,000 tons from commercial and multifamily buildings. Multifamily buildings in the WMA can subscribe for organics collection like other commercial properties; households in those buildings receive a kitchen pail, outreach material, etc., just like single-family properties. Organics from the WMA are composted at either Recology Grover or Newby Island, and San Bruno’s at Pacheco Pass.

San Francisco: The City of San Francisco began piloting residential food scraps collection in 1997, which evolved into the Fantastic Three in 1999 (trash, single-stream recycling, and food scraps mixed with yard trimmings). In 2001, organics service was offered to the city’s 7,900 apartment buildings (six or more units), and in 2009 the program became mandatory for all households. A recent rate change helped push the straggler apartment buildings to add organics collection service, and the city conducted a few pilot projects in 2014 to assess tactics for increasing participation in apartment buildings. About 160,000 tons of organics (residential and commercial) are collected annually and composted at Recology’s Jepsen Prairie Organics.

Colorado

Boulder: Boulder has had citywide food scraps collection for all single-family households since 2009. Trash is collected weekly, and recycling and organics are collected every other week (EOW), with organics processed at Western Disposal and A1 Organics. Tip fees at the landfill are less than half the cost of composting tip fees, but the landfills are further away, and the City of Boulder is committed to diverting organics and recycling. A major programmatic change in Fall 2014 was to allow meat, bones and dairy — when introducing the program in 2009, the city elected not to include these materials due to concerns about the potential impact these items might have on the foraging behavior of wildlife (particularly bears). The city has monitored wildlife, including looking at surrounding communities that allow meat and dairy, and decided to allow them to increase diversion. Residents were sent a letter and given door-hangers about bear-resistant trash and organics carts. The city already allowed food-soiled paper, along with BPI-certified compostable bags and food service products.

Boulder County: Residential food scraps collection is established in the city of Louisville, as well as unincorporated Boulder County to the south of the city of Boulder. Lafayette started collecting residential food scraps in 2014 as well. A recent report conducted for Boulder County on composting capacity highlights the dynamics of facilities in the area, potential tonnages, etc., and shows there is ample capacity in the area for future growth.

Denver: The Denver Compost program was launched as a pilot in 2007 for food scraps and yard trimmings collection, and became a fee-based service in 2010. A $2 million loan in 2013 from the City’s Department of Environmental Health helped purchase organics collection trucks (they had been leasing one) and carts, to enable the program to slowly expand. The city added a collection route in January 2014, with service currently available to 4,500 homes. Two more routes are being added in January 2015 (each route can service between 2,100-2,500 homes). Trash and recycling are paid through taxes, but the subscription fee for organics is $9.75/month. Households receive a 95-gallon cart, a kitchen pail and a sample of compostable bags, with all food scraps and soiled paper collected by the city weekly, and composted at A-1 Organics. The 10-year plan is to have 8 collection routes.

Connecticut

Bridgewater: The town of Bridgewater started a pilot program in April 2014, offered to all 1,100 households in the town. About 140 households have signed up for the service, which collects food scraps and soiled paper, and currently has no cost to residents. Participants received a kitchen container, roll of compostable bags and a curbside cart, along with a brochure on how to participate. An average of 9.65 pounds (lbs)/household/week are collected, with under one percent contamination. The organics are collected by All American Waste and composted at New Milford Farm, less than 6 miles away, which has tip fees that are $20 to $30/ton less than disposal. “We are still in the process of transitioning the program over to be permanent,” says Eric Fredricksen of All American Waste. “We see a lot of value in this and we are working to grow our routes.” Trash and recycling in Bridgewater is subscription based, so Fredricksen is trying to develop operational efficiencies for the new food scraps service, while keeping the existing customer base happy.

Illinois

Oak Park: The City of Oak Park piloted residential food scraps collection in 2012, and expanded citywide in 2013 as a subscription service. About 740 households are currently participating, in addition to 6 multifamily buildings (another 40 or so units), and an estimated 10 lbs/household/week of food scraps and soiled paper are diverted to Willow Ranch for composting. Oak Park has PAYT pricing; organics service is an additional $14/month, and is weekly excepting for December to March, when it becomes EOW.

Iowa

Cedar Rapids: The City of Cedar Rapids continues to allow its 39,400 households to place vegetative food scraps in their 35-gallon yard trimmings cart, a service started in 2001. The next step may be to allow baked goods. The Solid Waste Agency has been working with local grocers and institutions to allow more organics into the composting operation.

Dubuque: The City of Dubuque initiated Iowa’s first curbside program dedicated to food scraps collection several years ago, and within three years participation from about 230 households reached the maximum capacity allowed in its composting facility’s permit from the Iowa Department of Natural Resources (2 tons/week). In April 2013, Dubuque contracted with Full Circle Organics for processing, and expanded service to all city customers. Residents may use their current yard trimmings container, subscribe for a dedicated 13-gallon cart ($1/month and includes a kitchen container) or even use a yard trimmings bag with an attached yellow City sticker, and can divert all food scraps (with the assistance of BPI-certified compostable bags) along with grass clippings, leaves, and other yard debris. However, service still remains seasonal (April-November).

North Liberty: The town of North Liberty, a suburb of Iowa City, introduced residential food scraps collection in September 2014. Residents received a curbside cart (with a refundable deposit) for weekly collection of all food scraps and soiled paper, which are composted at the landfill. Yard trimmings are collected separately in bags imprinted with “Johnson County Refuse,” available for $1.65 each at several local stores. The food scraps program is intended to inform Iowa City’s own plans for collection, which may start up sometime in 2015.

Kentucky

Lexington: The City of Lexington began piloting food waste collection in 2011, allowing some residents to place food scraps in their yard trimmings cart. Participants received a kitchen pail and can place all food scraps and soiled paper in the yard trimmings cart, collected weekly and taken to Lexington Municipal Composting. Lexington’s program is a partnership between the Division of Waste Management and the local nonprofit Bluegrass PRIDE, which specializes in community education and outreach, whereby the city contracts with them to work on education for residents, door-to-door visits, presentations, etc.

Louisville: Louisville Metro began piloting wet/dry collection in 2014 for the businesses and residences it services in the Central Business District. The impetus for the program is an 11 percent recycling rate in the District, and Metro expects this rate to jump up drastically. A brown cart is for “wet” food scraps and soiled paper, and is serviced 2 to 6 times per week depending on the building’s/businesses’ need. An orange cart is for all nonorganic “dry” waste and recyclables. Case studies from several District hotels shows over 65 percent waste diversion, and a cost reduction in waste service bills of around 30 percent.

Maryland

Howard County: After a mini-pilot in 2010, Howard County began adding full collection routes to its residential food scraps program. Currently three routes, with a total of about 15,000 households, are eligible for the opt-in program, of which about 5,900 have signed up. All curbside materials are collected weekly, and services are paid for through an enterprise fund (i.e., a line item on property taxes). Residents choose between a 12-, 35- or 65-gallon cart and can include vegetative food scraps, soiled paper and yard trimmings, composted at the county’s Alpha Ridge pilot-scale composting operation, which is utilizing an ECS aeration system and covers. Before adding more routes to the program, increased composting capacity will be needed (either at Alpha Ridge, or another local processor).

Takoma Park: The City of Takoma Park started a residential pilot for food scraps collection in 2013, offered to 365 households. In 2014 the program became available to all 3,200 households in the city; about 1,300 are currently signed up. Compost Crew, a subscription collection service, continues to pick up from about 500 of these households, although the city plans to absorb them into its program in 2015. There is no fee to participate, and households receive a 5-gallon bucket and sample roll of compostable bags. Setouts are averaging 11 lbs/household/week (no yard trimmings), processed at the Prince George’s County composting facility, which has been pilot testing a GORE® cover system.

University Park: The town of University Park began piloting curbside food scraps collection for 50 households in 2011, funded in part by a $15,000 grant, and added another 100+ households in 2013 (the town has 900 households). Residents were given a kitchen pail, compostable bags and a 5-gallon bucket. The food scraps are collected weekly by the town and composted at the National Agricultural Research Center in Beltsville.

Massachusetts

Cambridge: The City of Cambridge has a long-standing drop-off program for residential food scraps, and in 2013 launched a curbside pilot for up to 800 homes. “Our city is committed to organics collection,” says Randi Mail, the city’s Recycling Director. “I waited for years to run this pilot until we were ready.” Participating households get a 13-gallon curbside cart, a vented kitchen pail and a one-year supply of compostable bags. While there is no cost to participate, two online forms are required, an interest form (for the building), and an acknowledgement form (per household), to show they understand the program and received kitchen pails, compostable bags, etc. Buildings up to 12 units can be in the pilot program. The pilot is averaging 6.65 lbs/household/ week, which is less than some neighboring communities with pilots, but based on a prepilot waste audit, this is an 85 to 95 percent capture rate (higher if considering weight loss from the vented pail). Organics are collected weekly and composted at Rocky Hill Farm.

Hamilton/Wenham: The town of Hamilton tested residential food scraps collection in 2009 before expanding the program in 2012 to all 3,600 households in its jurisdiction (including the sister city of Wenham). Food scraps and soiled paper are collected in 13-gallon carts, picked up weekly by a split-body truck with recycling on the other side; organics are composted at Brick Ends Farm. Residents are allowed one 35-gallon trash container collected EOW for free. Overflow bags may be purchased for $1.75, and can be placed out weekly (which cuts down on hauling efficiencies, because the trash truck still runs each week). Since implementing the program, Hamilton’s solid waste tonnage has decreased by 27 percent, and Wenham’s by 18 percent.

Ipswich: Ipswich piloted residential food scraps collection in 2011, and after one year moved to a subscription program, offered to all 5,000 households with curbside trash collection (432 are currently subscribed). The cost to households is $1.30/week, and includes a 12-gallon curbside cart, plus free compost. All food scraps and soiled paper are permitted (yard trimmings can be placed in kraft paper bags), collected weekly and composted at Brick Ends Farm. Trash collection is paid through taxes, but limited to 35 gallons, providing an incentive to sign up for the food scraps program (the cost for organics is less than a weekly overflow bag of trash).

Manchester By The Sea: The town of Manchester By The Sea rolled out curbside residential food waste collection starting in April 2014 to all of its 2,400 single-family households (everyone received a cart, no sign-up needed). The town decided to skip a pilot phase based on the success of the source separated organics (SSO) programs in nearby towns like Hamilton. An enthusiastic committee of 15 residents and a volunteer group of 50 people put together a marketing program and Boy Scouts distributed the 12-gallon organics carts to houses. All organics and soiled paper are permitted, but no yard trimmings (there is a drop-off program for yard debris), collected weekly in a split body truck and composted at Brick Ends Farm. The town is working towards EOW trash collection. Composting tip fees are 45 percent less than the incinerator in Middlebury. A Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (MassDEP) grant offset costs for carts and marketing materials.

Salem: Starting in April 2014, the City of Salem offers food scraps collection for up to 1,250 households. So far 950 have subscribed. “There is no fee for residents to participate, but the process for signing up includes several steps,” explains Julie Rose, Business Manager for Salem. “First, they complete a survey online and are sent an email explaining the rules and how to get a cart. They then come downtown and must sign a copy of the rules before getting the cart.” This approach has been successful, with about 80 percent participation (weekly set out rate) and an average of 10.5 lbs/week/household of just food scraps and soiled paper (no yard trimmings). The program was funded by two grants from MassDEP (for technical assistance and curbside carts). Black Earth Compost collects and processes the material. The pilot period is two years with the possibility of a third year extension. “We recently put our recycling and solid waste contracts out to bid, which resulted in a huge savings, some of which could be allocated to fund a citywide program in the future,” says Rose.

Michigan

Ann Arbor: The City of Ann Arbor began collecting residential food scraps in 2006, with about 11,000 “subscribers” out of 43,000 households. Residents must purchase the cart ($25 for 32-, 64- or 96-gallons), and the service is covered by taxes for garbage service. A recent change allows all food scraps, not just vegetative, mixed with yard trimmings, and participants are given a kitchen pail, which they may line with compostable bags. The organics are collected by the city seasonally (April-December), and processed at a municipal site operated by WeCare Organics.

Mackinac Island: The historic tourist destination of Mackinac Island continues to collect residential food scraps by horse-drawn trailers, as it has since 1992. Organics are collected in compostable bags (residents are charged per bag for trash and food scraps), and composted with yard trimmings and manure at the municipal facility on the island.

Minnesota

Hennepin County: Communities in Hennepin County began offering residential food scraps collection in 2005 (Wayzata) and new programs continue to come online each year. The majority of programs keep food scraps separate from yard trimmings, largely due to the Emerald Ash borer — the Minnesota Department of Agriculture has Hennepin County under quarantine, meaning yard trimmings must be processed (ground) before moving outside of the area, where two of the composting facilities are located. In addition to small, dedicated carts, several other methods are used for separate food waste collection. For instance, a popular service in the area is cocollection with trash (food scraps go in a thick compostable bag, placed in the trash cart). In other communities, food scraps are cocollected with yard trimmings (scraps placed in compostable bag, placed in yard trimmings cart).

In February 2014, the Hennepin County Board approved a requirement for Minneapolis to collect food scraps citywide starting in 2015 (it has had several small pilots), and a requirement that county staff provide a schedule for the rest of the communities in Hennepin County (there are 47 in all). The city of Minneapolis has 106,000 households with 1 to 8 units (about 60 percent of the population); the timeline for rollout is 25 percent of households in 2015, with the remaining 75 percent in 2016, staggered to allow for purchasing of carts, trucks and hiring staff. The program will be opt-in, where all residents pay for the service but must sign up to receive a cart dedicated to food scraps (yard trimmings will continue to be collected separately in residents’ own cart or compostable bags).

Hutchinson: The City of Hutchinson serves about 6,000 households, which are provided with 8 compostable bags per month at no cost to keep participation rates high, and contamination low. All food scraps and soiled paper are allowed, collected weekly and composted at Creekside, the city’s facility. Residents are given the option of EOW trash collection, which saves them about $20/month, and has helped the city divert 75 percent of its municipal waste (organics are about 50 percent, with recycling making up the remaining 25 percent).

New Jersey

Lambertville: In May 2014, the City of Lambertville started a food scraps collection pilot for 100 homes, funded in part by a $10,000 grant. Participants pay $65/year and receive a curbside cart, kitchen pail, compostable bags and an informational brochure. All food scraps and soiled paper (no yard trimmings) are collected weekly by the city, averaging 10 to 11 lbs/household/week, and composted at Ag Choice. Several residents have reported decreasing from 3 bags of garbage per week to just one bag.

Princeton: Princeton piloted a food waste collection subscription service starting in 2010, and now offers it as service to all of its 9,500 households. Subscriptions are $65/year for weekly collection of all food scraps, soiled paper and yard trimmings, and participants receive a 32-gallon cart, kitchen collector and a supply of BPI-certified compostable bags to line the kitchen collector.

New York

New York City: New York City (NYC) began piloting residential food scraps collection for 30,000 households in 2013, and expanded to about 100,000 households in 2014, plus 151 apartment buildings (representing an additional 16,959 units). (See summary of the pilot’s first year in the accompanying article, “New York City Pilot Organics Collection Program.”) The pilot officially goes through July 2015. A waste characterization study from 2013 shows that 31 percent of NYC’s waste stream consists of compostable organics. Besides the benefits of diverting those materials from disposal, implementing a cart-based collection system for food scraps is expected to deter the city’s rodent problem (currently most bagged trash is placed at the curb without a container). Residents also have the option of taking food scraps to a network of drop-off sites throughout the five boroughs, where organics are collected and then processed in the city (see “Greenmarkets Facilitate Food Scraps Diversion In NYC,” February 2014).

Tompkins County: Households in Tompkins County are getting options for managing their food scraps. The county launched a curbside pilot for 442 units in 2013, and expanded service up to 1,236 units in 2014, spread out over four jurisdictions (Town of Ithaca, Town of Ulysses, Village of Trumansburg, and City of Ithaca). It also added five drop-off sites around the county in 2014 for households that don’t have service through the curbside pilot. Curbside participants were given a 13-gallon cart, a kitchen pail, compostable bags and outreach materials (letter, brochure, magnet, and decal). “Based on the successes and failures of other programs, we sought to maximize participation and minimize contamination by providing free supplies,” says Leo Riley, Tompkins County Assistant Solid Waste Manager. “Having conducted extensive research, it was determined that compostable liners offered residents the added incentive for a clean program to collect food scraps for recycling.” Residents place a “Fork ‘em Over” replacement sticker on their cart when they need more bags. The program averages 11 lbs/household/week of food scraps (no yard trimmings), taken to Cayuga Compost.

Ohio

Several communities offer residential food scraps collection in Ohio. Waste Management allows yard trimmings customers in Fairborn, West Milton and Miami Township to include food scraps. Huron began offering SSO in 2009, adding food waste to the yard trimmings subscription, and extending service year round. Luckey replaced its poorly performing recycling program with an organics program that also targets recyclable paper (bottles and cans are still collected monthly). And most recently, a pilot program in Athens was conducted from May-September 2014 by The Compost Exchange to test the feasibility of organics collection (the city is considering it for 2015).

Oregon

Bend/Redmond: The communities of Bend and Redmond began offering yard trimmings plus raw fruits and vegetables collection in 2010 as a subscription service. In Bend, 3,919 households subscribe to weekly organics collection, and diverted 1,636 tons in 2013, which were composted at Deschutes Recycling. In Redmond, 2,639 households subscribe for weekly organics collection and in 2013 diverted 1,722 tons.

Marion County: The cities of Salem and Kaizer have been collecting residential food scraps since 2010, with service offered to about 48,000 single-family households. The communities have weekly collection of trash and organics, and biweekly recycling collection. A PAYT pricing structure allows residents to reduce their trash cart to 20-gallons. All organics are permitted in the green cart, including food-soiled paper (napkins, pizza boxes, etc.), but compostable bags and compostable paper packaging are not, as specified by the processor, Pacific Region Compost.

Newport: In July 2014 the town of Newport rolled out a residential food scraps and yard trimmings program to 2,400 households. The service adds $6.59 per month to a customer’s bill for weekly collection of the 65-gallon organics cart (trash and recycling are also collected weekly), with the possibility to opt-out. With an aggressive PAYT pricing structure, residents have the ability to offset the cost by downsizing their trash container. Thompson’s Sanitary Service provides collection.

Portland: The City of Portland piloted residential food scraps collection in 2010 and went citywide to all 147,000 single-family households (up to four units) in 2011. The city implemented less-than-weekly trash collection with the rollout of the organics program, and is now targeting multifamily buildings, about 200 of which are on the program so far. In 2013, 76,000 tons of residential organics were collected, roughly 10 percent of which are food scraps, and composted at Nature’s Need and Pacific Region Compost. The city does Spring mailings to people in multifamily buildings, reaching about 18,000 units/year, and in 2015 will expand this to reach 50,000 units. “From our vantage point, EOW garbage collection has been very successful,” reports Arianne Sperry in the city’s Solid Waste & Recycling office. “Since the food scraps collection program started three years ago, Portland residents have reduced garbage going to landfill by 36 percent. No other single program change could make such a significant difference.” The EOW trash collection was also key to Portland’s high participation rate in the food scraps program — a field study showed that almost 80 percent of Portland households are placing food scraps in the green cart.

Pennsylvania

State College: Residential food waste collection was tested in State College in 2010 and expanded borough-wide in April 2013 to 3,400 households (opt-out). All food scraps and uncoated soiled paper are now permitted in the program, along with BPI-certified compostable bags and yard trimmings. Residents can choose from a 35-, 65- or 96-gallon organics carts, all the same cost (bundled with trash and recycling), and also receive a kitchen container.

Texas

Austin: The City of Austin launched its curbside pilot for food scraps collection at the end of 2012, and added about 6,500 households in February 2014. All food scraps, soiled paper and yard trimmings are permitted, collected weekly and composted at Organics By Gosh. Austin’s aggressive PAYT pricing gives residents the chance to save money when diverting more to composting and recycling. For instance, downsizing from a 96-gallon cart to a 32-gallon cart provides an annual savings of $226.80.

San Antonio: The City of San Antonio piloted residential food scraps collection in 2011, and expanded to a subscription-based program in 2013, offered to 120,000 households for $3/month. Participants receive either a 48- or 96-gallon cart, with weekly collection of food scraps and yard trimmings. Currently about 19,000 households are subscribed, with 4,829 tons collected in FY 2014, composted at New Earth Soils & Compost. Starting in Fall 2015 through 2017, the program will go citywide to all 344,000 households, and transition from subscription into an embedded/opt-out part of the trash and recycling service. Also at that time the city will move to a PAYT tiered rate structure.

Vermont

Brattleboro: The town of Brattleboro piloted food scraps collection for 150 homes in 2012, and made the program permanent in 2013. Currently, 900 households are on the program, with weekly collection of organics and recyclables in a side loading split-body truck with three compartments (containers; recyclable paper/cardboard; food scraps and soiled paper). Trash is expensive, at a fee of $100/ton plus collection, compared to $45/ton to tip at the Windham Solid Waste Management District’s composting facility. The program currently averages 10 to 12 lbs/household/week of food scraps (only minimal yard trimmings), with very low contamination. A 2014 survey showed that 75 percent of participants use BPI-certified compostable bags, and many freeze or refrigerate food scraps to control odors before setting them out on collection day. As part of the statewide organics disposal ban (Act 148), Vermont also mandates that all residential trash programs utilize PAYT starting July 2015. Brattleboro expects this will encourage another 1,000 homes to join the organics program.

Washington

King County: King County began offering residential food scraps collection to its 38 jurisdictions in 2004 (Seattle operates separately), completing the rollout in 2011. It reaches about 319,500 single-family homes, and 59 percent are in subscription-based programs: currently about 225,500 households are signed up for food scraps and yard trimmings collection. More than half of the communities collect organics EOW, and most have EOW recycling, while only Renton has EOW trash. Households subscribed divert about 27.4 lbs/week, of which about 2.1 lbs/week is food and food soiled paper. While disposal of yard trimmings in residential trash is prohibited, many multifamily buildings contract directly for removal of yard debris, and don’t have an organics cart for food scraps. The city of Bellevue embedded food and yard trimmings in its new contract for multifamily buildings (one 96-gallon cart per building, more at an extra cost), and the county expects other cities to follow suit as new contracts come up for bid. Currently, about 4,242 multifamily buildings in the county have food scraps collection.

Seattle: The City of Seattle introduced curbside yard trimmings collection in 1989, included vegetative food waste in 2005, and then expanded to all food waste in 2009. This service is required for the 147,950 single-family households, unless exempted for backyard composting (6,183 households), as well as for the 5,843 multifamily buildings (five or more units), representing 149,618 units (only 25 buildings were exempted due to space constraints). In 2013, the city diverted 134,761 tons of organics, including 6,290 self haul tons, that were processed at Lenz Enterprises (see “Composter Brings On Residential Food Scraps Stream,” December 2014) and Cedar Grove Composting (the latter until the Pacific Clean facility comes on line). In 2014, Seattle passed a law requiring all organics (including food-soiled paper) from all sectors to be diverted to composting beginning January 1, 2015. Starting July 1, 2015, a fine of $1 per violation may be assessed against single-family customers with more than 10 percent organics (visually) in their carts or cans; a $50 fine can be assessed against multifamily and commercial customers after two warnings.

Tacoma: The City of Tacoma rolled out its “brown bucket” food scraps and yard trimmings program to single-family households and duplexes in 2012, and in 2013 went to EOW trash collection, with aggressive PAYT pricing. About 49,000 of the city’s 55,000 households subscribe to the organics service, and received a curbside cart (first one is free, additional cart is $3/month), which is picked up EOW (alternating with trash), a kitchen container and a brochure. All food scraps and yard trimmings are permitted, but no soiled paper or compostable bags, as requested by the processing facility, Compost Factory. In the first year of the program Tacoma captured an estimated 16 percent of available food scraps, and an informal lid lifting of the organics carts in 2013 showed that about 30 percent of setouts included food. A comprehensive waste characterization is planned for 2015 to better gauge how much food remains in the trash.

Wisconsin

Fitchburg: The City of Fitchburg piloted food scraps collection for 400 households in 2012 through December 2013; future collection requires local processing capacity.

Madison: The City of Madison’s pilot for residential food scraps, started in 2011, continues to serve about 600 homes. Starting in 2013 the organics collected in Madison are sent to the low-solids anaerobic digestion (AD) facility at University of Wisconsin, Oshkosh, followed by composting. Madison tentatively plans to expand the pilot to 1,600 homes in the Spring/Summer 2015, with construction of its own AD facility anticipated for 2016 and citywide SSO rollout in 2017.

Rhodes Yepsen, Marketing Manager for Novamont North America, was formerly an editor at BioCycle. Since 2007, he has conducted the BioCycle nationwide survey, “Residential Food Waste Collection in the U.S.” He currently sits on the Board of Directors at the US Composting Council and the Biodegradable Products Institute.