New York City’s Sanitation Department is making headway in its commitment to expand organics collection to serve all New York City residents by the end of 2018.

Nora Goldstein

BioCycle January 2017

NYC Will Have Largest Organic Waste Curbside Collection Program in Nation

“DSNY’s Expansion of Food Scraps and Yard Waste Collection in Queens Makes Program Available to More Than 961,000 Residents”

So read the headline of a November 14, 2016 press release from the New York City Department of Sanitation (DSNY) that announced DSNY’s expansion of food scraps and yard trimmings collection to residents in Queens’ Community Board 11. With this last rollout of 2016, approximately 11 percent of New York City (NYC) residents (more than 961,000 people) now have curbside service available, making the program the largest in the nation in terms of the number of residents with access, according to DSNY.

Residents are encouraged to use compostable bags for their food scraps (top) to help keep the bin clean, but are allowed to use clear plastic liners for convenience (bottom).

DSNY collects about 10,500 tons/day of refuse from New York City households and institutions, and about 2,000 tons/day of recyclables. Waste collection from the commercial sector is performed by private haulers licensed through the NYC Business Integrity Commission. Organics — including yard trimmings, food scraps and food-soiled paper — make up about one-third of the waste collected by DSNY.

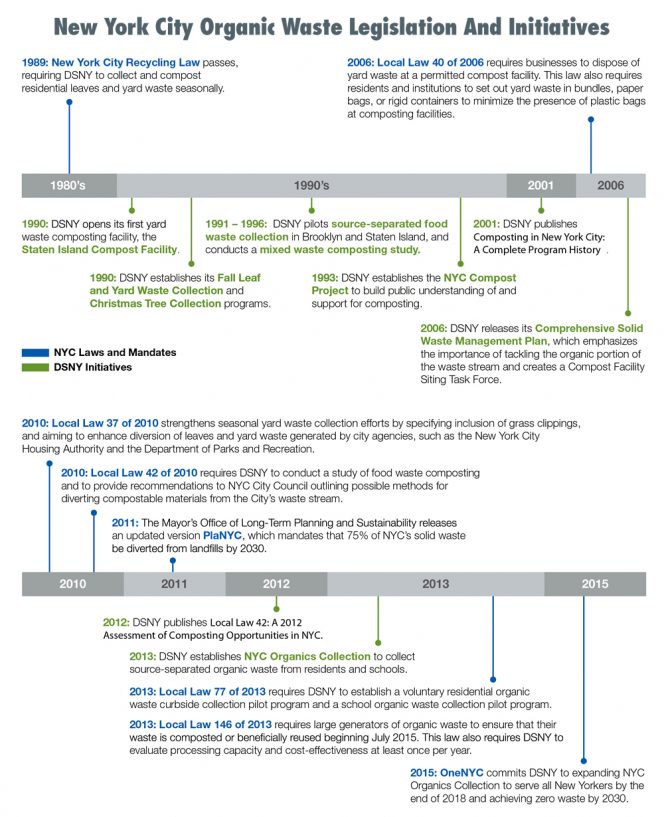

The current effort to divert source separated organics started in 2013, when Local Law 77 was passed by the New York City Council. The law required DSNY to establish a voluntary residential organic waste curbside collection pilot program and a school organic waste collection pilot program serving a minimum of 100,000 NYC households and 400 schools. Then, in 2015, Mayor Bill de Blasio released OneNYC (One New York: The Plan for a Strong and Just City) that committed DSNY to expand its organics collection to serve all New York City residents by the end of 2018, and achieve zero waste to landfills by 2030.

NYC is made up of 59 Districts and has a population of over 8.5 million people. DSNY operations divide the Districts into sections, and each section is divided into specific routes that collect from all demographics — single-family homes to large apartment buildings, and a population that speaks a diverse variety of languages. Each route is designed to meet productivity requirements (e.g. a citywide average of 10.7 tons/truck for refuse routes) as defined by NYC’s contract with the sanitation workers union, Teamsters Local 831. To date, part or all of 10 Districts receive residential curbside food scraps collection. While DSNY is mandated to provide the organics collection service, residential participation is voluntary. The Department of Education requires participation by schools chosen to be in the organics program, however, these schools do not receive fines for nonparticipation.

Residential Rollout

To roll out a residential neighborhood for curbside collection— like in the Queens 11 District in early December — all eligible households receive a starter kit that includes an indoor kitchen container, instruction brochure, and either their own 13-gallon outdoor brown bin with a locking lid or a 21-gallon bin to share for the building (if there are between three and nine units).

Large apartment buildings (with 10 or more units) and households in mixed-use buildings along commercial strips require a different roll out strategy. “Each building operates like its own mini city and requires commitment from the building management to set up an organics program that the residents can participate in,” explains Andrew Hoyles, DSNY’s senior manager for organics outreach. “For these buildings, DSNY established an enrollment program to join curbside organics collection.” DSNY and its nonprofit outreach partners recruit building by building to get the commitments of building management and staff to properly maintain organics bins and educate tenants on how to participate. As of late 2016, 635 apartment buildings with nearly 42,000 households are participating in organics collection.

DSNY Commissioner Kathryn Garcia (at podium) during a press event to announce expansion of NYC’s residential food scraps collection in a Brooklyn neighborhood. As part of the event, DSNY compost is applied to a street tree to demonstrate program benefits.

One of the biggest challenges in this program has been to develop the infrastructure to separate the bags from the organics. “We ultimately prefer all bags and bin liners to be compostable, but until we get to scale, we are allowing clear plastic liners for the bins, and we are seeing that the conventional shopping bag is more commonly used than the compostable bags available for sale, since they are ubiquitous and ‘free’,” she adds. That behavior could change when a law passed by NYC requiring a 5 cent charge on carryout bags takes effect on February 19.

Leaves and yard trimmings can be set out in brown paper lawn and leaf bags, or loose in an unlined container. Residents can also use the brown organics bin for leaf and lawn waste. Any branches thicker than a half-inch are collected by the Parks Department. “DSNY discontinued its seasonal leaf collection service in 2007, but we were able to bring it back this fall,” notes Louise Bruce, Senior Program Manager, NYC Organics at DSNY.

A DSNY field team manages the program’s rollout in each district, which includes a private vendor who hands out the bins, and nonprofit partners who conduct outreach during bin deliveries. “People are receptive,” says Kamil Krawczyk, senior manager for field operations, who leads the bin delivery team. “They want to know what it is for, and how to participate correctly. Almost 100 percent of households accept the bin.” A 2015 telephone survey among 500 randomly selected residents in pilot areas found that 69 percent of those who reported receiving bins put organics out for collection.

One effective outreach strategy has been to conduct street tree care projects using compost produced in NYC in the neighborhoods receiving bins, so residents see how the compost gets used as a positive benefit to the neighborhood. “It really helps people to understand why we’re doing the program,” adds Hoyle. “I had one person say they didn’t want the brown bin, but that they did want the compost. This provided me an opportunity to connect the dots.”

One effective outreach strategy has been to conduct street tree care projects using compost produced in NYC in the neighborhoods receiving bins, so residents see how the compost gets used as a positive benefit to the neighborhood. “It really helps people to understand why we’re doing the program,” adds Hoyle. “I had one person say they didn’t want the brown bin, but that they did want the compost. This provided me an opportunity to connect the dots.”Portions of all five NYC boroughs — the Bronx, Brooklyn, Manhattan, Queens and Staten Island — participate in organics collection. Standard residential collection service in NYC includes one day per week recycling service and two or three days per week refuse collection. Organics collection is being implemented using three strategies based on forecast modeling that analyzes fleet capacities, resident behavior including tons discarded and recycling diversion rates, and labor considerations including route lengths and contract productivity requirements. Three types of service include: once per week organics collection with a rear loader truck; twice per week organics collection with a dual-bin truck, in which organics and refuse are collected in separate compartments on the same truck; and three times per week on dedicated apartment building collection routes in high density neighborhoods, where sufficient buildings have enrolled to participate.

Internal Acceptance

Critical to the success of the residential organics collection program is acceptance by NYC’s sanitation workers. “Commissioner Garcia has visited each of DSNY’s 59 garages to speak with sanitation workers during roll call about the Department’s 2016 strategic plan, which includes a strong focus on zero waste,” notes Chief Keith Mellis, Assistant Chief in DSNY’s Bureau of Public Affairs. “We use roll call at the start of each shift to teach our workers about new programs and explain the benefits, in this case, of diverting organics. Each garage has a Smart Board and it can be used to show educational videos. Training DSNY’s workforce is a big part of achieving NYC’s Zero by 2030 plan, and we use it to reinforce what happens on the street with trash, recycling and organics.”

Keeping sanitation workers informed about organics operations is also important. “For example, when beginning collection in a new district, Commissioner Garcia will use the time during roll call to explain how organics are managed, from the curb to the composting facility,” explains Bruce. “We recently produced a video for both the general public and employees, called ‘Counter to Compost,’ which outlines this process and highlights one regional compost producer, McEnroe Organic Farm. It’s motivating for our employees, from the frontlines to management, to see the material transformed into a resource and to see that our work is having a real impact.”

Introducing a change like organics collection “was a little bit of a jump,” explained Commissioner Garcia, “as Sanitation has been doing things the same way for 150 years. So it was exciting when one day, I was in Manhattan and a Sanitation Worker told me about a homeless shelter that was having a rat problem. He suggested to me that the shelter enroll in the organics collection program because the rat problem was due to the food waste in the trash bags. The shelter is containerizing the food waste now, and the rat problem was eliminated. I felt like we had turned a corner. We are not just getting the people who are environmentally minded to participate and support the program, but are solving other problems too, such as removing the meals from the rats.”

Food Scraps Drop-Off

Residents not served by the curbside collection program may utilize food scrap drop-off programs offered throughout all five boroughs. No meat or dairy products are accepted at the drop-off sites, which are located at NYC’s Greenmarkets, subway stops, community gardens, public libraries and elsewhere. “There are close to 90 drop-off sites managed by DSNY’s nonprofit partners, including GrowNYC and NYC Compost Project host organizations,” explains Bruce (see sidebar). “In addition, New York City has more than 200 volunteer-run community composting sites throughout the five boroughs, and many accept food scraps from neighbors. DSNY sees these sites as the vanguard of organics diversion and provides them with resources and technical assistance through its NYC Compost Project.”

In 2016, as DSNY worked to expand the number of drop-off sites, its partners have tested different models, including unstaffed drop-off bins. The goal is to continue to add drop-off sites efficiently and in locations with a lot of foot traffic, while maintaining the quality of the material being dropped off, keeping contamination to a minimum, adds Bruce.

The most recent initiative, “Share My Bin,” combines curbside collection and drop-off. This is a voluntary program that encourages residents receiving NYC Organics curbside collection to open their bins up to neighbors who may not have one. DSNY is piloting the initiative in one neighborhood receiving organics collection service, by providing residents with a Share My Bin sticker that can be affixed to the lid of their brown bin. Once the bin is set out on the curb for collection, passersby can drop off their organics.

“By expanding drop-off sites and launching Share My Bin, we are testing new ideas and making it possible for New Yorkers who are excited about organics diversion and composting to start participating immediately,” said Garcia. “Our philosophy is if it works, great! If not, we will try something else. I call it adaptive management. I am a big believer in giving something a try and am okay with having to say it didn’t work.”

Garcia is a big believer in New York City’s community composting program, too. “Community composting provides a visualization of what DSNY is rolling out citywide with food scraps recycling,” she added. “A lot of neighborhoods have community gardens that include composting. People get to see the transformation of food scraps to compost that is used in the garden. This really shows the circularity of the program. We also illustrate this circular loop when we roll out an organics collection program in a district. DSNY staff gives away bags of NYC compost, and we demonstrate how it can be used.”

Residents not served by the curbside collection program may utilize food scrap drop-off sites in all five boroughs. No meat or dairy products are accepted.

Organics Processing

In 2016 (as of 12/22), DSNY collected more than 22,500 tons of food scraps, yard trimmings, leaves, and Christmas trees from residents and schools. Contamination of organics collected from residents is low at approximately 5 percent by weight. Most contamination in both the residential and institutional organics is plastic bags.

Organics collected curbside on Staten Island are delivered to DSNY’s Staten Island Compost Facility (see sidebar), which is operated by WeCare Organics. Organics collected curbside in Manhattan, Brooklyn, the Bronx, and Queens are delivered to private transfer stations, which then sort and aggregate material before sending it to regional composting or anaerobic digestion (AD) facilities. The majority of the material accepted at drop-off sites is composted at community-based composting sites managed by the NYC Compost Project nonprofit partners.

In the beginning of the pilot, DSNY had to rely on fledgling infrastructure to handle and process the organics loads from the residential pilot and school programs. For instance, until the fall of 2014, some of the material was taken to Peninsula Compost in Wilmington, Delaware, which closed in October 2014. None of the facilities had infrastructure to do extensive presorting to remove large amounts of contaminants, which were prevalent in the school materials (see “New York City Organics Collection,” January 2015, which provides detailed information about the first 18 months of the pilot).

To address contaminant management, DSNY is requiring all vendors receiving source separated organics from the Department to install mechanical preprocessing equipment to remove inorganic contaminants, such as plastic liners, packaging and serviceware, from organics streams in-city, before they are composted or digested. In July 2016, DSNY awarded (after a procurement process) over $47 million in contracts to six vendors to process organics from DSNY’s collection and food scraps drop-off programs. The bid solicitation required bidders to own or operate (or have an agreement with the owner or operator to use) a facility within 30 miles of New York City that could serve as the delivery location for DSNY collection trucks. Given this proximity requirement, all six vendors will receive organics at transfers stations within city boundaries, where preprocessing will be done.

“DSNY is committed to building a program that balances resident needs, i.e., clean bins, with processor needs, i.e., minimal plastics and contaminants,” explains Anderson. “Thus we allow clear plastic liners, and are installing preprocessing equipment at transfer stations to give us more ability on the back end to manage contamination. Overall, the evolution of NYC’s organics recycling program has been a learning curve. The residential rollout is a chicken-and-egg situation where we needed to get the front end [collection] started in order to develop the back end [processing]. And to optimize the back end, we needed to get as much material as possible coming in on the front end. In reality, it’s been a parallel process, and right now, we are in the middle of optimizing both ends!”

The six vendors, and the tonnage/dollar amounts awarded are: Waste Management of NY LLC: 75 tons/day (tpd), $15.75 million; American Recycling Management LLC: 65 tpd, $12.93 million; Brooklyn Transfer LLC: 50 tpd, $8.21 million; WeCare Organics: 20 tpd, $6.57 million; Hi-Tech Resource Recovery Inc.: 20 tpd, $1.99 million; and Regal Recycling Co. Inc.: 20 tpd, $1.6 million. These six vendors will be responsible for up to 250 tpd of mechanical processing capacity in anticipation of the organics recycling program’s future growth.

Mechanical preprocessing equipment named in the bid included DODA Bio-Separators, Ecoverse’s Tiger, and Scott’s Turbo Separator, which have a throughput of 10 to 20 tons/hour. The contract gives vendors the option of choosing one of these three technologies or equipment that is of equivalent functionality. Waste Management, for instance, has developed and installed its own system incorporating DODA processing technology, called the CORe®. These technologies produce a more homogeneous, blended output of organic waste, providing composting and anaerobic digestion facilities with a more reliable, consistent feedstock. They also give vendors the ability to control the moisture content of the output and appropriately pretreat the material for its end use.

To date, equipment installed includes the Ecoverse Tiger at DSNY’s Staten Island Compost Facility and Waste Management’s CORe system installed at the Varick Transfer Station in Brooklyn. Organics processed by Waste Management are being hauled to the Newtown Creek Wastewater Treatment Plant in Brooklyn, operated by NYC Department of Environmental Protection.

While the DSNY contracts are for processing residential and institutional organics (the latter is primarily schools), contractors can use the equipment for commercial organics as well. “While DSNY ramps up residential collection, these companies can supplement the incoming organics feedstock with commercial streams,” notes Bruce. In July 2016, NYC began implementing its commercial organics law. Certain businesses are now required to separate their organics waste. These include arenas and stadiums with 15,000 or more seats, large food manufacturers and wholesalers, and food service within hotels of 150 or more rooms.

New York City is committed to making investments such as the preprocessing equipment as it works to achieve its goal of sending zero waste to landfills by 2030. “We cannot achieve our ambitious goals without making substantial investments in new technology and infrastructure,” concluded Commissioner Garcia during the BioCycle interview. “New York City has a proven record of making sustainable waste management infrastructure a priority. For example, we have spent nearly $1 billion over the last decade to develop a resilient and sustainable network of rail-based and marine transfer stations. At the end of the day, if we don’t make long term investments like these, we will be penny wise and pound foolish.”

Corrected January 17, 2017