Audits at 17 schools found students generate more food waste at lunch than an initial estimate of 0.1 lbs/student, creating a baseline for prevention and recovery steps.

Mallory Feeney

BioCycle March/April 2017

In October 2015, the Iowa Waste Reduction Center (IWRC) at the University of Northern Iowa began a year-long project focusing on industrial, commercial and institutional (ICI) food waste generators throughout rural communities in the state. Funded by an $83,000 Solid Waste Management Grant from U.S. Department of Agriculture Rural Development, the project had one goal — to reduce the amount of food waste going to the landfill.

The IWRC provided hands-on technical assistance that often resulted in full food waste audits, which included observations of food management and serving practices, disposal methods and costs, and waste sorts. The ICI category that was most receptive to learning about their food waste and making changes were K-12 schools. “We never expected schools to be the most receptive to food waste audits, but the opportunity to work with students, teachers, staff, and administrators was the highlight of the project,” notes Jennifer Trent, Environmental Specialist at the IWRC who oversaw implementation of the grant-funded project.

Waste Sorts

The IWRC worked with 12 school districts that encompassed 29 schools. Multiple types of assistance were offered; the most beneficial, not only for the project but for the schools, was a waste sort. Seventeen individual schools within seven school districts around the state requested assistance in conducting a cafeteria waste sort. “It’s messy but physically conducting a waste sort is the most effective way to know exactly what is being thrown away, and how much,” explains Trent. Additionally, the waste sort provides actual generation rates and allows for baselines to be calculated and goals to be set.

Central Community School District students with teacher, Ann Gritzner (right), showcase the new sign for their composting site.

Sorting Results

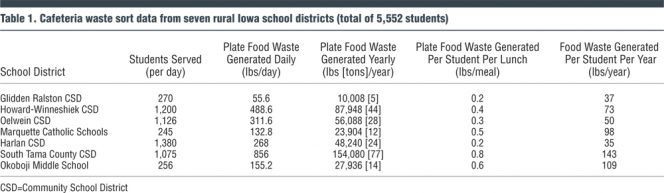

As the project came to a close on September 30, 2016, the IWRC compiled results from each participating district (Table 1). Analyzing and extrapolating the data showed the districts generated 408,204 pounds (204 tons) of food waste per school year — all of which was being landfilled. To break down the findings further, the average annual food waste generation rate of 5,552 students within the 17 schools is 0.4 pounds per lunch or 74 pounds per student per school year.

“One of the biggest takeaways from this project is the need for accurate food waste data so we can plan and prepare methods to help prevent and reduce food waste across all sectors,” explains Trent. In 2015, the IWRC had estimated food waste generated in Iowa by each ICI entity using available industry factors. The factor used to estimate plate food waste generated by students was 0.1 pounds per student per lunch. “I thought we had adequately estimated a general baseline for how much food waste was being generated in each K-12 school district in Iowa but after comparing our waste sort data to our estimates, we realized the factor used to estimate food waste for schools was grossly inaccurate,” she adds.

IWRC’s data found three of the school districts generated almost double the food waste estimated, one school district generated triple, one generated more than five times, and another two school districts generated more than six times the food waste estimated. “What we calculated from conducting waste sorts was that each student generates an average of 0.4 pounds per lunch,” says Trent. “This is precisely the reason we need to continue to conduct food waste sorts, so we can provide K-12 schools with accurate factors to estimate food waste.”

Initiatives Already In Place

Some of the schools IWRC worked with had already taken steps to learn about, or even prevent and reduce food waste. For example, one school allows seconds of fruits and vegetables to all students and seconds of main courses to athletes on days where leftovers will be disposed rather than served (e.g., on a Friday), or if there won’t be enough leftovers to serve the following day. Additionally, students are encouraged to take less initially; kitchen staff are trained to remind students to eat what they take. This cafeteria offers foods rather than automatically serves foods so students can select only items they intend to eat. Another school (not audited) was collecting all fruit and vegetable kitchen waste and taking it to feed livestock at a local hobby farm.

Central Community School in Elkader, Iowa was already way ahead of the food waste reduction curve. With help from a dedicated student organization, the Central Green Team, Central Community had built a composting site in 2015 for its lunchtime food waste and compostable materials such as napkins, paper towels and paper serving boats. However, due to lack of experience, the composting pile was not breaking down during cold winter months and the school quickly was running out of space to compost. Additionally, the composting site was situated right next to the Turkey River where leachate could become an issue.

Trent visited the site in order to troubleshoot the decomposition issue. She recommended combining smaller piles into one large pile to help maintain heat during winter months, as well as suggested moving the composting site away from the banks of the river. With IWRC guidance, students from Central Community School began work on improving their composting site by following Iowa regulations for siting, and notifying the Iowa Department of Natural Resources of their activities. A farmer from the local area bales corn stalks to provide the school’s composting operation with a reliable source of carbon. While mixing of food waste and carbon is initially done by a manure spreader, the City of Elkader turns the pile with an end loader to help manage the composting operation. Finished compost is given away and used on school grounds.

The composting paid off. Central Community School reduced its daily lunchtime food waste by nearly 60 percent and drastically reduced landfill expenses. Annually, the school diverts 7.2 to 10.8 tons of food waste. The Central Green Team continues to manage food waste in a sustainable manner and is seeking new ways to prevent food waste in the first place. A group of students who focused on solving the composting challenge received statewide recognition when presented the 2016 Governor’s Iowa Environmental Excellence Award.

Next Steps

The Rural Iowa Food Waste Reduction Project provided the IWRC a window of opportunity to really gauge food waste in K-12 schools with actual data and hands-on assistance. “Being able to be in the schools and explain to students why we were conducting cafeteria waste sorts was invaluable,” notes Trent.

It also became evident that reducing school food waste is no easy task. Multiple districts listed staff shortages as a major challenge towards implementing full-scale food waste reduction. In response, Trent recommends that schools have a passionate champion to spearhead initiatives. In addition, many steps can be taken behind the scenes in the kitchen, through collaboration or administration changes, such as recess before lunch, letting students help plan the menu, giving menu items jazzy names, creating a table for uneaten and unopened milk and foods to be donated or even extending lunch time to at least 25 minutes.

Working in rural communities gave the IWRC a small sample size, and set the stage to assist other districts in the state. The actual waste sort data can be used to create accurate factors that will allow other entities to estimate how much food is being wasted and identify practices that will reduce this amount and potentially save money. IWRC and the Iowa DNR plan to continue these audits in K-12 schools.

Reducing food waste will take a continuous combined effort from K-12 schools and their communities. “We provided rural K-12 schools with data on how much food they are throwing away — most don’t think they throw away all that much — and we provided them with simple, cost-effective strategies to reduce this amount and also reduce costs associated with disposal,” concludes Trent.

Mallory Feeney is a student employee with the Iowa Waste Reduction Center at the University of Northern Iowa and has worked on multiple food waste reduction and diversion projects for the IWRC.