What is the “state of the State” in terms of composting capacity and compost markets in California? Location of infrastructure, market drivers and impact of organics-related laws are discussed.

Craig Coker and Jeff Ziegenbein

BioCycle March/April 2018

California is home to 39.5 million people, many of whom live in the densely developed Los Angeles, San Diego, and San Francisco Bay metropolitan areas. According to the California Department of Resources Recycling and Recovery (CalRecycle), an estimated 76.5 million tons of solid waste were generated statewide in 2016, with 44 percent recycled or composted and 56 percent disposed.

California is home to 39.5 million people, many of whom live in the densely developed Los Angeles, San Diego, and San Francisco Bay metropolitan areas. According to the California Department of Resources Recycling and Recovery (CalRecycle), an estimated 76.5 million tons of solid waste were generated statewide in 2016, with 44 percent recycled or composted and 56 percent disposed.

In order for California to reach its legislatively mandated (AB 341, 2011) statewide recycling rate of 75 percent by 2020, more than half of the solid waste currently disposed would need to be source reduced, recycled, or composted. Several legislative actions have been taken to achieve that goal. In 2014, AB 1826 was passed, and went into effect on January 1, 2016. Generators of more than 4 cubic yards (cy)/week of organic materials are required to divert those wastes to recycling (that mandate expands to generators of 2 cy/week or more in 2019). In 2015, AB 876 was passed, which requires counties to quantify the amount of organic waste that will be generated in the county over the next 15-year period and identify new or expanded organics recycling facilities that will be able to handle this material.

In 2016, California legislators passed SB 1383, creating a framework for reducing Short-Lived Climate Pollutants that will require development of a comprehensive organics diversion and processing infrastructure to meet the bill’s targets of a 50 percent reduction in organic wastes disposed (over 2014 quantities) by 2020, and 75 percent reduction by 2025.

State Of Infrastructure

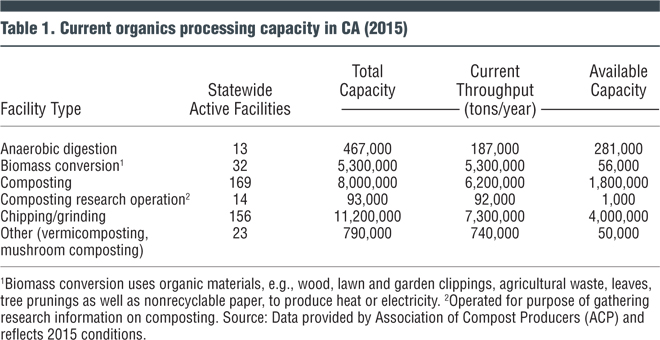

California has over 200 composting and anaerobic digestion (AD) facilities, but in-state management options for processing more organic materials are challenging (Table 1). Currently, in-state processing infrastructure is insufficient to properly handle all of the anticipated increases in collected organics. As is true elsewhere, siting, permitting, and building new organics management facilities are formidable obstacles due to cross-regulatory requirements and, in some cases, lack of public acceptance. In addition, the co-benefits of using compost (such as improved soil health, water conservation, and increased soil carbon) do not have a monetary value and are not well accounted for in typical market transactions.

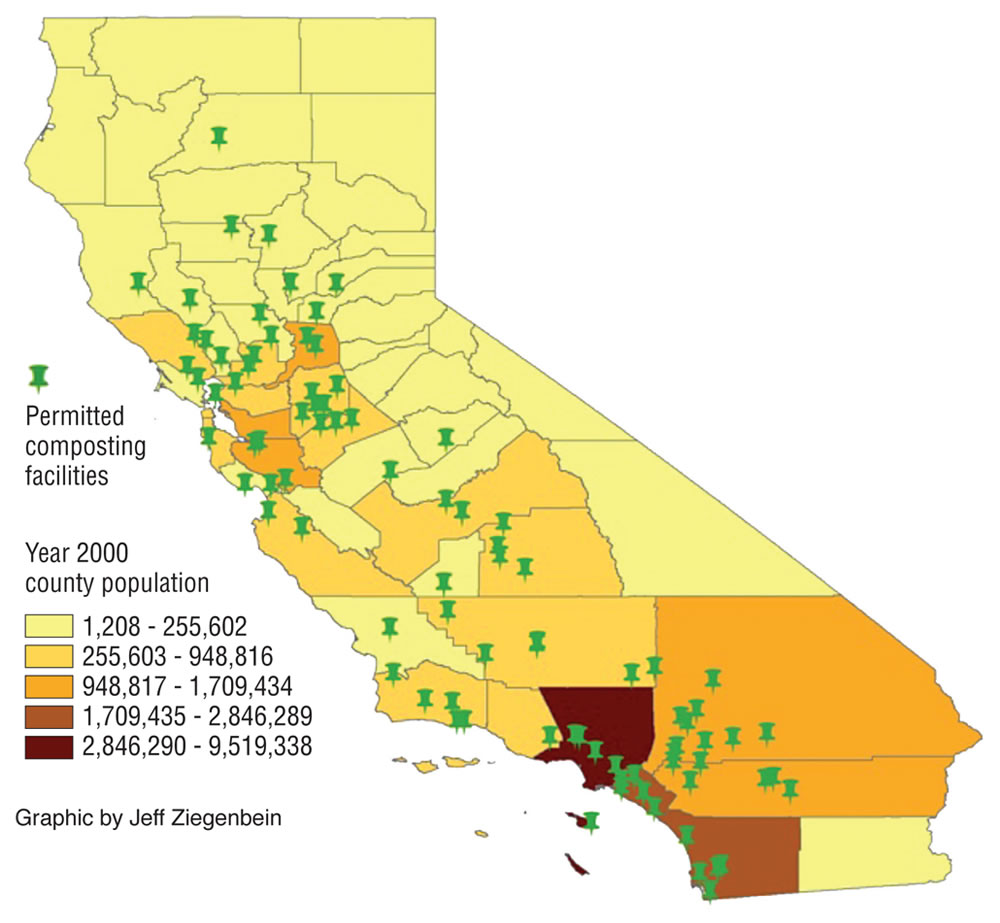

California’s compost manufacturing industry is diverse, with facilities ranging from small community composters to some of the largest operations in the U.S. Over 6 million tons of organic feedstocks are processed annually, producing about 20 million cy/year of compost (around 500,000 tractor-trailer loads). Geographically, the facilities are, for the most part, located in the outer regions of the large metropolitan areas, and in the agricultural region of the Central Valley (see map on facing page.)

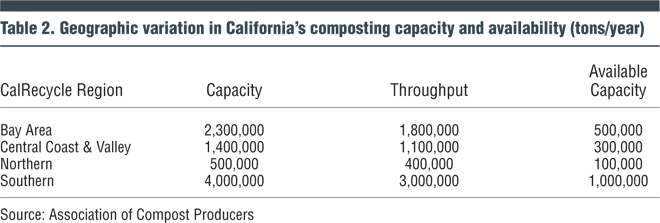

California is so large that many refer to it by different regions of the state. For example, CalRecycle commonly divides the state into five regions: Northern, Bay Area, Central Coast, Central Valley and Southern. There is disparity among the regions with regard to composting capacity, throughput and availability (Table 2).

Total available capacity in the state is 1.9 million tons, well short of the composting capacity believed to be needed to support diversion rates mandated by SB 1383. The first round of capacity assessments mandated by AB 876 have been reviewed by CalRecycle. The staff’s overall assessment is that while the initial data in the submitted capacity reports is helpful, it does not provide the department with a fully accurate picture of future organics processing capacity needed to address longer-term planning for organics infrastructure by counties and regional agencies.

With the impetus provided by SB 1383, CalRecycle is planning to implement provisions in the SB 1383 regulations to address some of the initial challenges. These include ensuring reported capacity is not double counted and is verified that it is available; ensuring collaboration among jurisdictions, facility operators, and others to facilitate common understanding of the capacity needs and the future planning needs; and hold cities, counties and regional agencies responsible for planning and identifying capacity if they lack sufficient existing, new or planned capacity.

Since the focus of SB 1383 is on reducing the impacts of climate change, CalRecycle has been successful at using the state’s Greenhouse Gas Reduction Funds (GGRFs) to spur development of new composting and anaerobic digestion facilities. In Fiscal Year 2016–2017, CalRecycle funded $24 million worth of composting and AD infrastructure.

CalRecycle has started an SB 1383 Infrastructure and Marketing Analysis that will include an assessment of the capacity of the organics processing industry in California, updating previous studies done in 2000, 2003 and 2010. The assessment is expected to be completed in late 2018. “This project, in addition to documenting baseline infrastructure information, will investigate how the organics processing and composting industry is responding to new and to current regulatory challenges,” explains Cotton, who conducted the studies for CalRecycle, and is doing the current assessment. “Specific questions about how these new challenges are affecting composters and processors will be added to understand the impact regulatory issues might have on the continued success of organics diversion in California.”

Compost Markets

Agriculture

The southern region of California, which includes Kern, San Bernardino, Ventura, Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside, San Diego, and Imperial counties, composts 3 million tons/year (about 50% of the state’s total processing capacity). Many in the California composting industry believe there cannot be growth in composting throughput in Southern California without significant improvement in market conditions. One reason is that the $45 billion agricultural industry is a big user of compost and the majority of those users are in the Central Valley, a 3 to 5-hour travel time from the southern region’s composting facilities. CalRecycle’s 2010 Assessment of Compost and Mulch Infrastructure estimated that more than half of the state’s compost is applied to agriculture lands.

A 2017 study of California almond growers by the University of California at Davis shed some light on the agricultural market for organic matter among that sector. California almonds have a crop value of $6 billion and are grown on over 980,000 acres. The researchers surveyed 6,192 growers, getting 1,120 responses (27%), asking about “organic matter usage” (composted manures and yard trimmings, uncomposted green waste and raw manure). The study noted: “Use patterns were significantly influenced by heavy and light users, farm size, and geographic region. Enhanced soil biology was the main benefit attributed to organic matter amendments by both users and nonusers. Nonusers showed greater concern for food safety compared to users, and all growers reported greater concern for food safety from manure. The greatest adoption of organic matter amendments occurred on small farms (≤420 acres) in the north San Joaquin Valley. Greater accessibility to manure correlated with presence of dairy farms. Poorer accessibility ratings by nonusers suggest access is a barrier to adoption, as opposed to nonusers having an undesirable view of the practice.

Water Efficient Landscapes

One potential boon to the southern California compost market is the Model Water Efficient Landscape Ordinance (MWELO). In 1992, the California Department of Water Resources (DWR) first published a model ordinance to help guide California’s cities and counties in improving the water efficiency of new landscapes. The ordinance was flexible to allow for creative and attractive designs for new landscapes. However, local adoption and enforcement was uneven. At the direction of the Legislature, in 2009 MWELO was strengthened and communities were given the choice to adopt MWELO or to adopt a locally written ordinance that would be at least as effective in conserving water. If a community took no action, State law required that MWELO be enforced nevertheless. By late 2010, hundreds of localities reported that they had adopted MWELO, while somewhat fewer reported the adoption of a locally written landscape ordinance.

The drought of 2014-2016 was considered the most widespread and severe water shortage since California became a state. At the height of the drought emergency in 2015, Governor Jerry Brown issued an Executive Order directing DWR to strengthen MWELO further. After public hearings, a third edition of MWELO was published, with changes effective as of December 1, 2015. The revisions included, for new or rehabilitated landscapes, a requirement that “compost, at a rate of a minimum of four cubic yards per 1,000 square feet of permeable area, shall be incorporated to a depth of six inches into the soil. Soils with more than 6 percent organic matter in the top 6 inches of soil are exempt from adding compost and tilling” (Title 23, Chapter 2.7, §492.6(a)(3)(C)).

All cities in California are required to ensure that all new landscapes adhere to water efficiency standards that are equal to or greater than the standards set forth in the MWELO established in 2015. Most did adopt the ordinance, but, in December 2017, the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) sued the cities of Pasadena and Murietta for failure to adopt it. There is also uncertainty about whether cities that adopted the ordinance are enforcing it.

Streambank restoration project in northern California installed Filtrexx’s GroSoxx filled with half-inch minus compost and plugged with plants for revegetation.

Healthy Soils Initiative

Another potential market booster is the California Healthy Soils Initiative. Governor Brown announced creation of the Healthy Soils Initiative in 2015 as part of the state’s climate initiatives, which aim to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 40 percent by 2030. The California Department of Food and Agriculture (CDFA)’s Healthy Soils Program will provide financial incentives and demonstration project funding for agricultural management practices that reduce GHG emissions by increasing carbon storage in soils and woody biomass on working agricultural lands. The program also is designed to provide tangible benefits to producers by supporting agricultural practices that increase crop yield, carbon sequestration, and increased water retention in times of flood or drought.

CDFA allocated $3.75 million in FY 2016-2017 from the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund for the 2017 Healthy Soils Program Incentives Program to provide funds to California growers and ranchers to implement conservation management practices that sequester carbon, reduce atmospheric greenhouse gases, and improve soil health. GHG benefits are estimated using quantification methodology and tools developed by the California Air Resources Board (CARB), USDA-NRCS and CDFA; soil health improvement will be assessed by measuring soil organic matter content. Grant awards of up to $50,000 each were announced in December 2017 and 42 of the 64 funded projects involved use of compost to reduce water usage and improve soil health.

“California has lofty goals and good intentions with the organics diversion and reduction programs,” notes Dan Noble, Executive Director of ACP. “There’s a mature compost manufacturing infrastructure with robust marketing programs. The state needs to ensure that sufficient resources are allocated to boost markets so they are able to meet the aggressive expansion mandates set by the state.”

Craig Coker is a Senior Editor at BioCycle and CEO of Coker Composting & Consulting near Roanoke, VA. He can be reached at ccoker@jgpress.com. Jeff Ziegenbein is Manager of Regional Compost Operations at the Inland Empire Utilities Agency, and President of the Association of Compost Producers (ACP), the California chapter of the US Composting Council. He can be reached at jziegenb@ieua.org.