Kayla Walsh

At a St. Paul, Minnesota museum, a banana peel is hurled into the “organics” collection bin. Walk across the street and another bin might be labeled “food waste.” Organics collection differs at school, work, and in public spaces. Distinct rules exist for food-to-hogs versus collection for composting. All this confusion can prevent residents and businesses from participating — or participating correctly — in organics collection programs. Minnesota’s organics educators met to discuss this messaging dilemma and asked: How do you communicate to the public in the most concise, consistent way to encourage a successful organics collection program?

In 2016, this group of representatives — including haulers, composters, cities, counties, and the state — worked together to publish an Organics Recycling Outreach Guide. Public and private sector educators voluntarily use this style guide to ensure consistent terminology, symbols, and colors. The guide advises educators to use the color green, to use the term “organics recycling,” and to accept food and BPI (Biodegradable Products Institute)-certified products. The guide also asks educators to use different terms depending on what happens to the organics after they’re collected. For example, signs might say “organics recycling for composting,” “organics recycling for food-to-animals,” or “organics recycling for food-to-people” depending on the collection scenario. Organics educators use this outreach guide across the state, but how does Minnesota compare to the rest of the country?

Survey Process

Minnesota has 9 composting sites that accept food waste and over 115 yard trimmings sites. About a quarter of the population has access to organics drop-off sites and 20 percent of residents have access to curbside organics collection. Most are voluntary or opt-in (i.e., choose to use the service). Anticipating continued growth, educators wanted to revisit the Organics Recycling Outreach Guide to make sure it was still applicable. They wanted to know how collection programs in other parts of the country communicate about organics recycling. To get a better handle on the norms across the country, an organics education team — which included representation from the City of Minneapolis, Dakota County, and the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency — issued a national poll asking:

• How do you title your program?

• What color signifies “organics?”

• What certifications for compostable products are allowed in collection programs?

Using SurveyMonkey, the team sent out a survey through the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, BioCycle, and the US Composting Council networks with this message: “Like many cities, the Twin Cities Metro Area (Minneapolis-St. Paul) is trying to reduce the amount of waste sent to landfills, which includes food and compostable products. As you may know, educating about composting/organics recycling can be challenging. Your survey results and upcoming residential focus groups will guide us in future program education and outreach.”

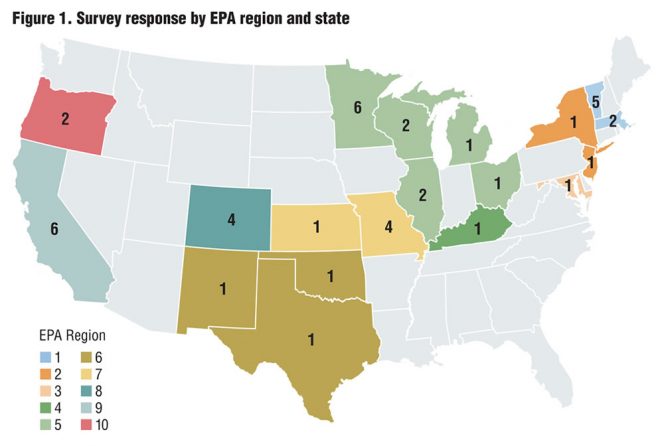

A total of 128 responses were received. To be adequate for inclusion, the response had to meet the following criteria: Complete over 50 percent of the survey; Accept food waste; and Only one response per program. That left 62 unique responses, 47 of which gave their location. Figure 1 shows the distribution of responses across the nation. A large percentage came from the Midwest and Central regions of the country. Missing regions are primarily in the Northwest and Southeast. The map also is only available for the 47 respondents that provided location information. Therefore, 15 responses are not represented on the map but are represented in Figures 2-4.

It’s important to note that the survey results cannot determine which terms are most effective, but they can start determining which are most popular based on the number of responses received. Using the 62 unique responses, a frequency analysis was done to look at the most used responses across programs.

Survey Findings

How Do you Title Your Program?

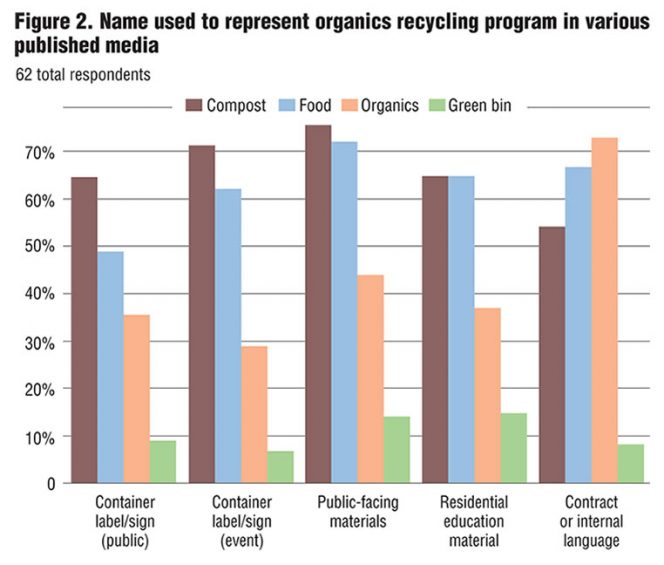

Despite several similarities, no clear program title emerged as the most popular across the nation. Picking a program term can be tricky. The term “organics” doesn’t always translate well to other languages and it confuses people with the organic certification used to describe food. The term “organics recycling” might get confused with traditional recycling. Some programs use “food waste” on their collection bins, but that is not inclusive of paper or compostable products. “Green Bin,” while easier to promote in residential communications, is not descriptive of the material going into the bin. The term “compost” is the product, not the feedstock that residents are being asked to put in the bin.

When asked what they title their program, respondents could choose from several options in the survey including: Compost; Composting; Organics recycling; Organics; Organic waste; Organics for composting; Food scraps; Food recycling; Food and yard waste; Food waste; Wasted food; Green bin; Other. The survey team grouped responses by those who picked a title that included the words compost, food, or organics. Respondents could select more than one, in which case they would be put into more than one grouping.

Figure 2 reveals that while waste educators use “organics” internally in contract language, they don’t always trust the public to understand that term. Instead, we see a rise in including the terms “compost” or “food” when interfacing with the public.

It should be recognized that some programs might have already adopted very successful terminology that is not the norm elsewhere. Making a switch could involve an expensive and potentially confusing process to relabel containers and update education materials. The term “Green Bin” consistently ranked the lowest, but perhaps that is a well-ingrained, successful program.

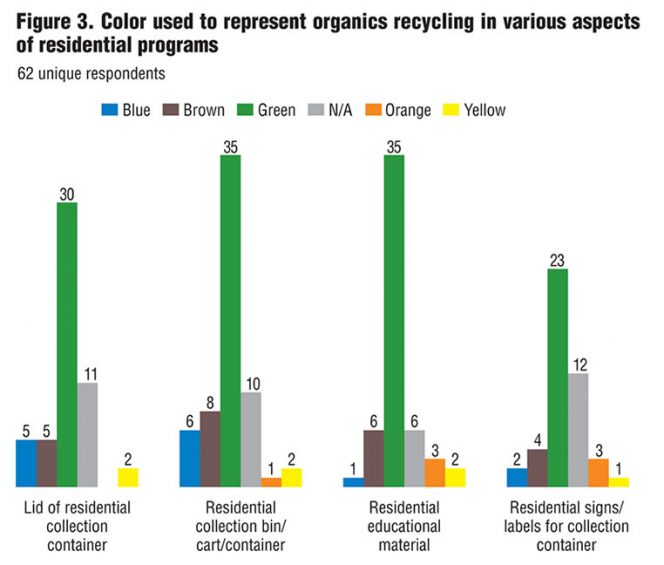

What Color Signifies “Organics?”

The Minnesota organics style guide recommended using green as the color for organics; Figure 3 shows that this was also the popular choice across the respondents. Green was selected as the key color used for lids, bins, carts, labels, and educational materials to represent organics collection.

Compostable Products Certification?

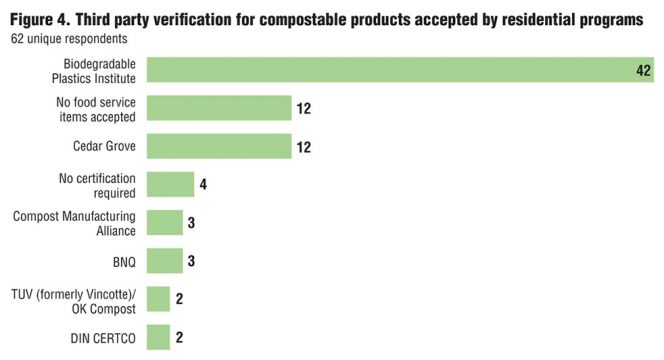

The survey asks, “What certifications for compostable products do you allow in your collection programs?” BPI (the Biodegradable Products Institute) was a clear frontrunner with 42 of the 62 respondents (68%) indicating they accept BPI certified compostable food service products. It should be noted that for programs that accepted third party verification, most identified that their material would be going to a commercial composting site that could handle compostable products.

What’s Next?

Having the right terminology is only the tip of the iceberg. To create lasting behavior change, program promotion should be tied with community-based social marketing, which uses targeted messages based on human psychology and decreases barriers to the desired behavior. These techniques are effective because they improve self-efficacy and eliminate user uncertainty. Examples include:

• Using less text and more pictures on container labels.

• Having face-to-face education like door-knocking proves to be most effective.

• Using social proofs is also an effective way of garnering behavior change, like saying “90 percent of your neighborhood participates in organics recycling.”

• Giving positive feedback when the behavior is done correctly (such as adding a cart tag with a happy face). This is more effective than giving negative feedback.

Consistent terminology helps to encourage better organics recycling, but much more can be done to help accomplish that goal. Co-locating recycling bins next to every trash bin and printing image-based signage are also key techniques to promoting behavior change.

Minnesota is still gauging the precise value to having consistent terminology in a particular region or community. The original premise that led to development of the outreach guide in Minnesota and the development of this survey was that using different terms would lead to confusion. Additional research is needed to determine how the public responds to these terms, and to evaluate what the impact of consistency is on understanding.

Survey Still Open

Minnesota educators will aim to use these survey results to start focus groups with the public around program title terminology. This survey is still open and we need your help to get a more comprehensive look at nationwide data. With more respondents, the survey results could reveal regional trends. Please represent your program and your state by taking our poll.

Kayla Walsh is an organics and recycling specialist at the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency. She also serves as the organics market development lead for the Minnesota Compost Council. Special thanks to Barbara Monaco (Minnesota Pollution Control Agency) for survey analysis and graphical development and to Jenny Kedward (Dakota County) and Kellie Kish (City of Minneapolis) for collaborating on survey development, outreach, and analysis.