Top: Loading one of four bunkers at the City of Medicine Hat’s pilot composting site. Labeling on the kitchen buckets (inset) reminds participants of accepted feedstocks. Photos courtesy of ECS and City of Medicine Hat

Nora Goldstein

The City of Medicine Hat in the province of Alberta, Canada, conducted a pilot project from April 2024 to January 1, 2025 to evaluate residential food scraps collection and an aerated static pile composting system. The initiative was recommended in the City’s 2023 to 2032 Waste Management Strategy. The City Council approved the strategy in November 2023. “On the same day, Council also approved the food waste pilot project, with a go ahead to get started in the spring of 2024,” notes Shane Briggs, Medicine Hat’s Waste and Recycling Manager. “We were pretty aggressive with our timing to get it launched.”

The Waste Management Strategy estimated that the City-owned landfill will reach its capacity in 2039. “The development of a new waste cell is estimated to extend the landfill life to 2054,” states the Strategy report. “The implementation of a new programs such as a food waste curbside collection program has the potential to further increase the capacity of the landfill.” The most recent waste audit, conducted as a baseline in the pilot area in April 2024, found that organics comprise 41% of what is in the trash cart, with food waste making up 84% of that organic fraction.

Medicine Hat provides collection of residential trash, recycling and organics to the city’s 21,000 households. Residents need to opt in to receive a green organics cart to use for yard trimmings and pay a one-time $50 service fee; collection is seasonal. “About 70% of households — roughly 15,000 — have a yard waste cart,” says Briggs. “We always have four side-loading collection trucks on the road servicing those carts. Collected yard waste is taken to our windrow composting site at the city waste management facility. A portion is used for the City’s biosolids composting operation.”

The pilots were supported by $400,000 in funding from the Green Municipal Fund managed by the Canadian federal government. The pilots were designed to evaluate the effectiveness of food waste collection and processing, gather critical data on waste generation, and actively involve the community in sustainable waste management practices. Dillon Consulting, Ltd. was hired to work with the City on all aspects of the pilots. Approximately 4,000 households were selected by the City for the food waste pilot. Participants were required to already have a green cart, actively participate in the City’s seasonal yard waste collection program, and be in one of the 15 collection zones identified as being eligible for the pilot. One of the side-loading yard waste collection trucks was used to service the pilot households.

Side-loading curbside collection truck utilized for the food waste pilot. Photo courtesy City of Medicine Hat

For the processing portion of the pilot, Engineered Compost Systems (ECS) was awarded the contract to design and construct a pilot-scale food waste covered aerated static pile (CASP) composting system with capacity to process 2,500 tons/year of food waste and yard trimmings. The system was set up adjacent to the existing yard trimmings composting operation. Installation took place in early summer of 2024.

Letters were sent to each pilot household to notify them of the upcoming food waste pilot and one week before it began, kitchen buckets to collect food waste and how-to guides were dropped off to be used by participants. All food waste and food-soiled paper were accepted, along with yard trimmings. The pilot did not include use of certified compostable liner bags to place in the buckets. Pilot participants were instructed to put the contents of their kitchen buckets into their green (organics) cart for collection on their regularly scheduled pick up day.

To support and assess the overall success of the food waste pilot, five main tasks occurred: public engagement, data gathering and analysis, waste collection analysis, technology review processing results, and conceptual plans. Extensive public engagement and gathering feedback, as well as the data collection and analysis activities, occurred in three main phases throughout the nine months. Included were three waste audits, three sample set out rate surveys, and one pilot-wide set out rate survey. Data gathered helped the City and its consultant develop a better understanding of pilot participants’ waste behaviors and identify whether these behaviors changed throughout the pilot.

Public Engagement Activities

Phase 1 (pilot initiation) of the public engagement program occurred from March to May 2024, Phase 2 (pilot midpoint) from September to October 2024, and Phase 3 from November 2024 to February 2025 (pilot end review). The activities included surveys, open houses, postcards, and distribution of kitchen buckets. Digital communication tools such as newsletters, social media campaigns (e.g., Instagram and Facebook), and the “Shape Your City” project page communicated updates and opportunities for residents to participate and provide input.

“Initially, awareness levels were moderate, but they improved as the pilot progressed due to targeted engagement such as newsletters, increased social media posts, postcards, radio and newspaper advertisements, and commercials,” notes the Final Report about the engagement strategy. “By the end of the food waste pilot, a substantial 85% of participants reported consistently using the provided kitchen buckets for food waste disposal, indicating a successful shift in behavior and a strong foundation for a future food waste program. This behavioral change was largely driven by participants’ recognition of the environmental benefits, such as reducing landfill waste and extending landfill life, as well as the social responsibility associated with sustainable waste management practices.”

Despite the overall positive reception, several concerns were reported consistently throughout the pilot, adds the report. “Participants expressed apprehensions regarding potential additional costs associated with a future food waste program, as well as issues related to messiness and pest control. The inability to use compostable bags was a recurring concern, with many participants advocating for this inclusion to enhance convenience and hygiene. These concerns highlight the need for the City to explore logistical and operational requirements to use compostable bags to improve the program’s success and acceptance.”

City-wide surveys were also sent out in Phases 1 and 3 to solicit input from residents beyond those involved in the collection pilot. “City-wide willingness to participate (including very likely and likely results) in a future food waste program increased 7% from Phase 1 (76%) to Phase 3 (83%),” according to the report, which includes detailed tables and charts on the findings. “Pilot participants had a higher likelihood of participating in a future food waste program throughout the three phases, ranging from 88% in Phase 1 to 94% in Phase 3.”

Findings from the three phases of engagement are available on the City of Medicine Hat’s food waste pilot website (scroll to bottom of page).

Waste Audit And Set Out Data

The intent of the waste audits conducted during the spring and summer was to measure the amount of food waste collected in the garbage and organics carts post pilot rollout, compare the results to the baseline audit, and assess any improvements as the pilot progressed. City staff collected waste materials including garbage, recycling, and organics carts from 10 households in different zones in the pilot areas Monday to Friday (50 households in total), which were audited by Dillon to determine the composition of the three streams. The report explains that “while waste audits typically track progress by measuring the percentage of specific materials in the waste stream, food waste alone cannot be fully assessed by percentage due to the seasonal fluctuations in other waste types. Therefore, the total kilograms of food waste generated per household in each stream was also calculated to provide a more accurate measure of the food waste pilot’s overall progress.”

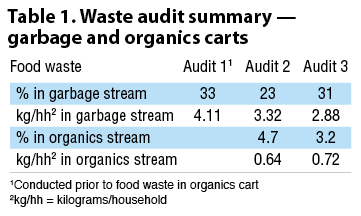

Table 1 summarizes the findings of the waste audits. The data reveals a 30% reduction in food waste in the garbage stream and a 12% increase in food waste in the organics stream between the first and third audits.

Table 1 summarizes the findings of the waste audits. The data reveals a 30% reduction in food waste in the garbage stream and a 12% increase in food waste in the organics stream between the first and third audits.

During the audits, Dillon also conducted a set out rate survey of the 50 households where waste materials were collected to help determine participation levels among households and assess whether participation improved over time. In addition, Dillon staff conducted a one-time pilot-wide set out rate survey for all households involved in the food waste pilot. “Measuring the frequency of cart set outs gave us an understanding of resident engagement with the food waste pilot,” explains Dallas Sutherland, Medicine Hat’s Superintendent of Collections.

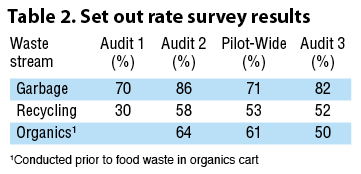

Table 2 summarizes the set out rate findings. Although organics initially had a high set out rate, over time, these rates became comparable to those of recycling. “This trend indicates that while pilot participants are engaging with the food waste pilot, their commitment may fluctuate or taper off slightly over time,” adds Sutherland.

Composting Pilot Assessment

The pilot-scale ECS composting system operated from April to December 2024. It had four bunkers, each positively aerated using HDPE pipe-on grade. Feedstocks tipped were mixed in batches using a portable horizontal mixer; piles were built over the aeration pipes using a front-end loader. Cabled temperature probes provided continuous feedback to the damper actuators, modulating airflow and controlling pile temperatures. Retention time in the CASP system varied from 21 to 28 days. The CASP system can compost 2,500 tons of material per year, with retention times varying from 21 to 28 days, according to ECS. “Despite the extreme cold, Medicine Hat was able to successfully process organics through the winter and keep diversion efforts going,” notes Baraka Poulin, Director of Business Development at ECS. If Medicine Hat proceeds with a full-scale system, it may incorporate heat recovery to mitigate the impact of frigid temperatures during winter.

The pilot program’s four composting bunkers viewed from the front with the portable horizontal mixer on left (top). Aeration equipment is in the back of the bunkers (bottom). Photos courtesy ECS

Medicine Hat was able to successfully process organics through the winter despite the extreme cold. Photo courtesy ECS

The City would like to shift its biosolids and yard trimmings windrow composting processes, which operate year-round and use a lot of real estate in the active composting area, to an aerated static pile system. Dillon provided a conceptual plan for about 30% of the total organic waste generated in Medicine Hat. The ASP design would accommodate an estimated annual 24,750 tons/year, including 3,300 tons of food waste and soiled paper and cardboard, 9,040 tons of yard waste, 12,125 tons of biosolids, and 275 tons of brewery effluent. Capital costs are estimated to be $9.5 million for an ASP facility of that scale, which then could be expanded as needed over time.

Next Steps

About 1,100 tons of food waste and yard trimmings were collected and composted from pilot participants. The City estimates that the cost to expand food waste collection citywide would be less than $4.00/household/month. “That is without accounting for a potential carbon credit from Alberta’s Carbon Offset Credit System,” explains Cory Manz, Medicine Hat’s landfill Superintendent “If we could get the carbon credits, it would cost less.”

The next step to roll out citywide curbside food waste collection is getting approval from City Council. “We recommended to City Council that the program be adopted citywide to both the residential sector and expand into commercial sectors in the second phase, and to approve $9.5 million for a new ASP composting facility per our conceptual plan,” says Briggs. “In a perfect world, we would have continued running the pilot and gradually expanded it, e.g., to 50% of households initially. This would have maintained the source separation behavior achieved with the pilot households, and utilize the insights gained through the pilot’s public engagement strategy for the roll out. At its July 2025 Council meeting, the matter was deferred for consideration — most likely by the next Council following the municipal election in October.”