Top: Photo sources: Community Food Rescue (left, top), Bright Beat (left, bottom), BioCycle (center, top), BioCoTech Americas Inc. (right, top), BioCycle (right, bottom) and Hudson Soil Co. (center, bottom)

Nora Goldstein

Back in 2007, BioCycle had a frank discussion with our readers. The subject was the “w” word, aka waste. I wrote in an August 2007 Editorial, “Most of us in the recycling and composting industry have struggled with this word for years. The struggle has to do with the fact that what we really are talking about are ‘resources’ in the waste stream, materials that have a higher and better end use than just being thrown in a landfill to rot. But ‘waste’ is a universal word and ‘resources’ is open to interpretation.”

It was pretty easy to transition from yard waste to yard trimmings, but where we got stuck is what word best follows “food” when it comes to what doesn’t get eaten, served, donated or recycled into a by-product (e.g., at a food processing plant). “I hate to say it, but waste works pretty darn well, especially because the food being discussed in that particular article, in essence was wasted, i.e., it didn’t get eaten on the plate, or too much was prepared for the number of meals to be served, etc.,” I wrote in the 2007 Editorial, noting that at the time, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, along with a handful of state solid waste agencies, appeared to have settled on the word “scraps.” However, the lack of conviction to stick with the word “scraps” was evident in the description on the EPA webpage: “Basic Information About Food Scraps: Food leftovers are the single largest component of the waste stream by weight in the United States. Americans throw away more than 25% of the food we prepare, about 96 billion pounds of food waste each year.” In a few short sentences, EPA used food scraps, food leftovers and food waste. Clearly, the agency also was struggling with terminology.

No Wavering On Compost

Fast forward to 2025, and BioCycle still interchanges the words waste and scraps when it comes to food that is not consumed by humans or animals. But one word that in our 66 years of existence we have never wavered on is compost. Ina Pincus, BioCycle’s editor since the publication was started as the journal Compost Science in 1960, was adamant about saving the word compost for what it is — a product that has gone through aerobic, biological decomposition of biodegradable materials, which includes undergoing mesophilic and thermophilic stages of composting, and has gone through a final phase of curing. We were not allowed to call source separated organics compost, nor material that had not been through the complete composting process, compost. Red ink, green ink, and in the final years of Ina’s editing, pencil — we never wavered.

Outside of home gardeners, organic farmers, some livestock farmers, and a handful of municipalities, compost was not widely known in the early years of BioCycle’s history. Recognition accelerated back in the late 1980s and early 1990s when close to two dozen states banned or restricted landfill disposal of leaves, grass and brush. Municipalities, counties, regional waste authorities, nurseries, farms and landscapers all got into composting and selling or distributing finished compost. A composting industry was born, and it was off to the races.

Co-Opting The Compost Name

New York City Mayor Adams introduces the “smart” food waste drop-off bin, labeled compost (top). Washington, D.C.’s new “smart” bin (above) is labeled food waste. Photos courtesy NYC Dept. of Sanitation and the District of Columbia’s Office of Waste Diversion.

I just looked up how co-opt is defined. Here are terms in the definition: “take over, appropriate;” “adopt for one’s own use;” and “divert or use in a role different from the usual or original one.” Based on those definitions, it is accurate to say that the word compost has been co-opted. It is very common these days for programs designed to collect source separated organics to refer to this stream as compost, e.g., put food scraps from your kitchen into a compost bucket, or to label the curbside or drop-off container the compost cart. It also is common at sorting stations in venues, cafeterias, restaurants, and elsewhere to label the bin for food waste/scraps “compost,” and the other bins “recycle” and “landfill.”

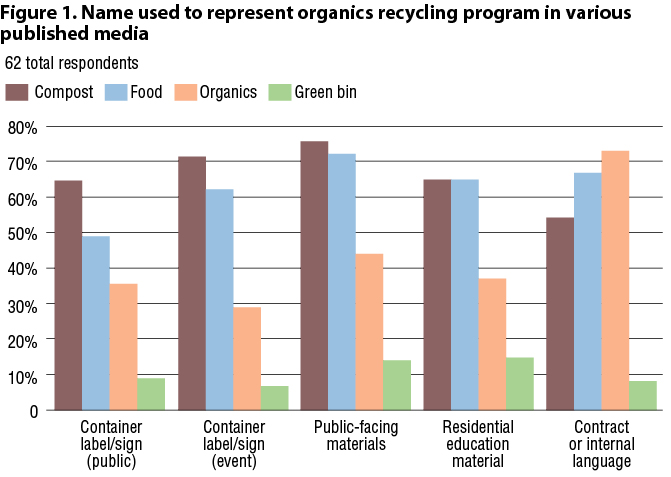

In 2019, Kayla Walsh, then with the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA), wrote an article for BioCycle titled “The Organics Recycling Messaging Dilemma.” The article shares the findings of a national survey organized by MPCA, the City of Minneapolis and Dakota County that queried municipal programs about how they title their program, what color bin signifies “organics” and what certifications for compostable products are allowed in collection programs. Figure 1, reprinted here from Walsh’s article, captures the name used to represent organics recycling in a program’s published media. She wrote, “the Figure reveals that while waste educators use ‘organics’ internally in contract language, they don’t always trust the public to understand that term. Instead, we see a rise in including the terms ‘compost’ or ‘food’ when interfacing with the public.”

The downside of using the name compost for the organics container is that people who don’t know what compost is may assume it is the food scraps they are placing in the bin. The majority of local government programs and food scrap collection subscription services that refer to the collection bin as “compost container,” do explain in their outreach and education materials how the loop is closed from the collected organics to the finished compost. A case in point is that many residential food scrap collection services include giving compost made from the households’ organics back to them as part of their subscription. While BioCycle does not call the organic material at the point of collection compost, that usage has become institutionalized in many programs and will likely not change.

The more troubling co-opting of the word compost has reared its head recently in the marketing of food waste dehydrators and fermenters to consumers. Many of the vendors call the device a home “composter.” As BioCycle has written about several times in the last couple of years (e.g., “Electric Kitchen ‘Composter’ Confusion, and “What Is Not Compost”), neither these devices nor their commercial-scale counterparts make compost in the device that meets the official definition, nor the compost product that BioCycle has been writing about since 1960. What these devices do is begin a process — thermally and/or with added microbes — that break down the food scraps into either a dried material, or a very partially “composted” material. The output must be further composted in order to actually become a compost. Full stop. Laboratory analyses of these outputs is the proof in the pudding.

At a commercial or institutional scale, BioCycle also sees co-opting of the word compost by companies selling machines that claim to make compost in 24 to 72 hours, or in some cases, five to seven days. These units, because most use forced air and amendment, definitely kickstart composting. But the material discharged is not compost. Full stop. Further composting and curing is necessary prior to usage, albeit perhaps in less time than composting in windrows or aerated static piles. Compost is a regulated product with standards, parameters and established laboratory tests to ensure that the material is indeed compost.

So yes, we are having that conversation again. It’s a bit more dicey than what to call food that is no longer edible by humans or animals. Food waste, food scraps — it’s all over the map. But compost ain’t compost until it’s compost.

This Commentary is dedicated to the memory of Ina Pincus Goldstein, who with her husband, Jerome Goldstein, created and led BioCycle to become the Organics Recycling Authority that it is today.