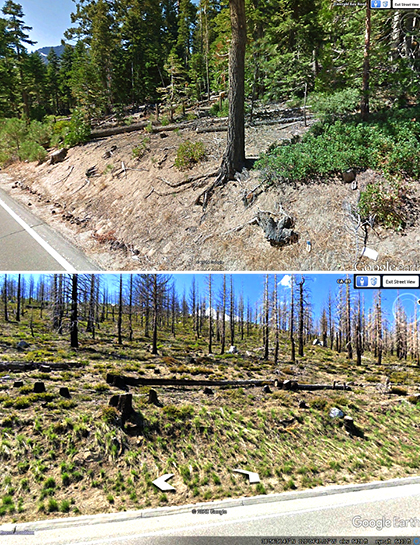

Top: Controlled burn as part of research study examining compost use for remediation. Photo courtesy of David Crohn, UC Riverside

Sally Brown

If you look at the literature, you’ll find a few papers comparing use of mulches and anionic polyacrylamide (aka PAM) for remediation of soils burned by wildfires. One study compared a bark mulch applied at about 5 tons/acre to PAM applied at about 100 lbs/acre. The real thing was much more effective than the synthetic substitute. The soil without anything in this study had overland flow from rainfall of about 3 inches and lost about 4 tons of soil. Adding the mulch cut the water flow in half and eliminated 90% of the soil loss. The PAM didn’t do anything.

A study done on slopes post fires in Colorado found that straw mulch did the trick even better than bark mulch. This study also tested seeding and contour felling (cutting trees so that they face perpendicular to the slope). The most and very effective treatment was the straw. If straw can do it, compost can do it better. There have only been a few studies that I could find where the benefits of compost amendment post fire were tested. One of these was done years after the fire. Another was done many months after the fire. The composts help to restore vegetation but the late application meant that most of the soil erosion had already taken place.

Soil loss is greatest the first year after a fire and decreases as vegetation returns. To be most effective and stop critical damage, composts have to be added as soon as possible after the fires die out. Right now, compost is not on the top of the list of accessible and critical tools to control erosion after fires. We need more research and more outreach to change this.

The best study I found had the fire department come in and do a deliberate burn just so they could get the compost down right after the fire. That is the way to test compost. David Crohn from the University of California Riverside tested green waste compost — both fines and overs — and biosolids compost. The composts were applied at 2.5 and 5 cm depths. They both worked. Runoff as well as the soil carried in the runoff were reduced by 86% to 97%.

University of California Riverside study tested green waste compost — both fines and overs — and biosolids compost to remediate soils deliberately burned as part of the project. Photo by David Crohn

This group currently has another study underway. Here they’ve partnered with U.S. EPA and the California Association of Sanitation Agencies to apply biosolids to an actual burn area. The study is located at Las Virgenes Municipal Water District in Calabasas, CA. The area was burned in part of the Woolsey fire in late 2018. Treatments including biosolids pellets, Class B biosolids, and biosolids compost have been applied to the burn areas. There is also a no amendment control. To date there have been 4 rain events since amendments were applied and data from those is being analyzed. The plots after amendment application, and then over a several month period, are below.

(1) Amendments applied to research plots at the Las Virgenes Municipal Water District, from right to left, are Class A biosolids compost, Class B biosolids, Pelletized biosolids and Control, established in December 2019. (2) Plots in January 2020 and in March (3). The pelletized treatment appeared to be the slowest to revegetate. Photos courtesy of Harry Allen, U.S. EPA

Continuing The Search

Not finding much in the literature I tried a different approach. I asked folks from California who work with compost. It turns out that all the way back in 2007, Matt Cotton, a composting consultant in the state, organized a demonstration project after the Angora Fire near Lake Tahoe. Compost (supplied by Grover Environmental) was applied post burn using a blower truck (donated by Peterson Pacific); hand-applied straw was used as the control. This was a high altitude site with a dry spring following application. As you can see in the next set of photos, the compost did well with plants starting to grow and no evidence of any soil loss.

Engineers from the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans) came to watch and some of them even tried it themselves. Cotton was able to do this demonstration on private property. He said that for lands not privately held, the cost of compost application is often a show stopper. In fact, I got an email from an old acquaintance after the CZU Lightning Complex Fire in northern California destroyed his friend’s home. He was asking for sources of compost to stabilize their hillside. Cost was not an object, he added. They just wanted to stabilize the slope. The key here is to get the agencies that are responsible for public lands to realize that being penny wise is really being tons of soil lost foolish when it comes to compost use.

Not all burned lands need compost. On level soil, what remains will likely stay in place. That is one way to reduce costs — use only where needed. Filtrexx has applied the lessons learned in developing socks and blankets for highways to burnt areas. The website shows pictures of compost socks at the toe of slopes post fire. These rolls of compost are likely highly effective in stopping the sediment at a point. If you want to stop the soil in place, you’ll likely need to go for the whole compost blanket.

On September 25, 2020, the San Diego Times Union reported that the City of San Diego offered free mulch to residents to spread on areas burnt by the Valley Fire that began in early September. Over 17,000 acres were burned. The offer to load up to 2 cubic yards (cy) of mulch at the city’s Miramar Greenery for use to stop soil erosion is a great gesture that serves two purposes: it gives residents a tool to use and it gives the city a way to distribute excess woody material. It will take a lot of 2-cy truckloads to make a dent on 17,000 acres, but at least it’s a starting point.

We have a handful of studies and even fewer demonstrations. I would bet that few in the U.S. Forest Service have heard about these projects or the folks involved. We need more of these studies and demonstrations with different materials applied at different rates. And we have to get this knowledge about compost use in the hands of those who likely don’t know our colleagues or their work.

The fact is that compost will work the same way on burn sites as it has on so many other types of soils and situations. For compost to work to stabilize soils after fires, the critical factor is to create a cover layer that will hold the soil in place. A cover will slow down the rain and give it time to soak in rather than run off. This is the same principle as compost use on highway right of ways. It is the basis of the Soils for Salmon program in western Washington where compost is added to rain gardens and new construction to help water soak into soil. We know how compost works and we also know how to apply it. Composters know how to apply to slopes. They know how to put compost in berms and blankets. They have blowers to spread the compost in hard to reach places.

Composters: This is a time to reach out to your communities, state Departments of Natural Resources and offer your services. Hopefully this 2-part series is enough of a primer and an inspiration to get composters to start talking about this end use.

Rampant fires and the smoke that surrounds us are clear signs that the climate has changed and not for the better. While compost doesn’t have the power to stop this part of the climate crisis it does have the power to staunch the bleeding. It can limit the destruction while we get serious with bigger solutions.

Sally Brown, BioCycle’s Senior Adviser, is a Research Professor in the College of the Environment at the University of Washington.