Top: Compost application for carbon sequestration research project (left). Community composting in Los Angeles (right). Photos courtesy StopWaste.org and CompostableLA

Juliana Beecher

The People, Food and Land Foundation (PFL) works at the intersection of community, ecology, and policy to restore and regenerate California’s soil systems and rural communities and economies. The nonprofit, which got its start in the 1970s as part of the small farm water and land rights movement, created a new suite of resources on composting and compost use in California specifically for municipal and county planners. The resources include a brief report on the existing inclusion of compost in general plans and climate action plans in California; an extensive guide on planning for compost development and use; data compiled on organic feedstock types and availability, and an assessment of current throughput of composting sites in the state.

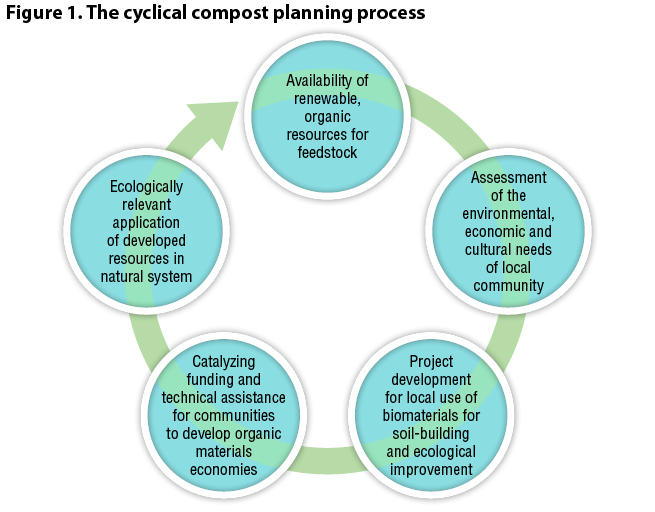

The project was spurred by a concern about SB 1383, the state law that requires jurisdictions to provide organics collection and recycling to all residents and businesses, and to procure recycled organic products (e.g. compost) for use — all with the goal to reduce methane emissions. The concern was that SB 1383 is being limited to waste management and perceived as a burdensome requirement to “begrudgingly deal with,” explains Stephanie Cain of PFL, who has a Master’s in urban planning and joined PFL to spearhead the project. PFL’s goal is to change the mindset around SB 1383 from a burdensome regulation to one of opportunity for the management of valuable “bioresources” to stimulate local economies, build soil health, mitigate hazards, and create community connection — while also diverting organics from landfills and reducing methane emissions. Figure 1 from the “Planning For Compost” guide describes the “cyclical compost planning process” when compost feedstocks are considered resources to be developed.

Planners are well-positioned to support composting and compost use in their jurisdictions, says Cain. The work of municipal planning departments is foundational to economic and community development as planners are tapped into communities and able to connect businesses and organizations with resources, partnerships, and funding sources. Planning departments are required to think more holistically about community needs and opportunities than other departments with narrower focus areas, such as public works, and they have a mandate to envision a project from collection to compost creation to its end use. The soup to nuts positioning combined with the fact that planners can influence land use ordinances and zoning codes — which can heavily impact the feasibility of siting composting operations of all sizes — makes them an important piece of getting local bioresources development right from the get go.

Windrow turning at Debs Regional Park compost hub in Los Angeles. Photo by Kourtnii Brown

In California, all cities and counties are required to have General Plans (GP). According to the General Plan Guidelines from the Governor’s Office of Planning and Research, these documents are “more than the legal underpinning for land use decisions; [a GP] is a vision about how a community will grow, reflecting community priorities and values while shaping the future.” GPs must include nine elements: land use, circulation (i.e. transportation, roads, etc.), housing, conservation, open space, noise, safety, environmental justice and air quality. These are legally binding documents, and all municipal ordinances must align with a jurisdiction’s GP, making them powerful tools that influence decisions around land use, infrastructure projects, access to public space, natural resource management, and more.

Compost Inclusion In Plans

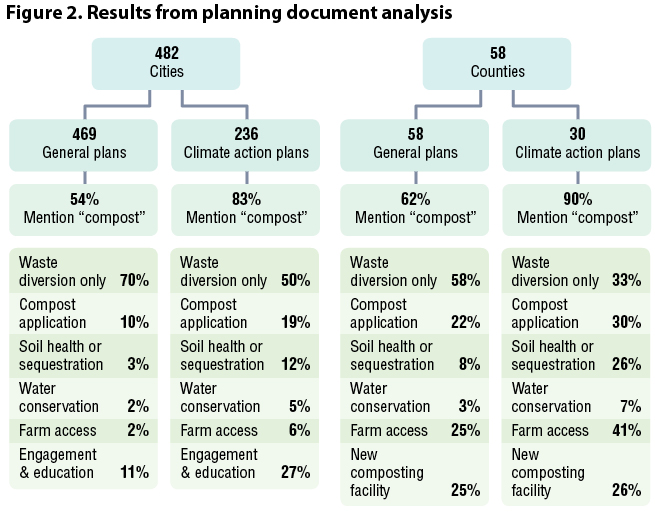

PFL performed a comprehensive review of all city and county GPs and climate action plans (CAPs) in California to determine how many mentioned compost and in what contexts. Only plans that included composting or compost application as part of a goal, strategy, policy, program, or initiative were counted. Mentions of composting or applying compost were not counted unless part of an explicit, actionable item.

Figure 2 shows the results of the comprehensive review. Overall, compost was mentioned more often in CAPs (83% of cities and 90% of counties) than in general plans (54% in cities and 62% in counties). Unlike GPs, CAPs are not legally binding documents.

A key difference between city and county planning is how these two types of jurisdictions think about compost. More city GPs and CAPs mentioned compost as a waste diversion strategy only (70% and 50%, respectively) compared to county GPs and CAPs (58% and 33%, respectively), while a greater percentage of county planning documents mentioned compost application (22% of GPs and 30% of CAPs) and/or farm access to compost (25% of GPs, 41% of CAPs). “Counties have more agricultural and open land to plan for than cities,” says Cain, “and many counties have existing compost markets and industries and are already actively considering the best use for the resource. Cities often have a harder time planning for compost outside of community gardens and urban food production. We’re hoping to expand those project ideas into soil building for resilience.”

There is also more planning for new composting facilities happening at the county level than the city level. According to the report, “some city planning documents also mentioned plans for new facilities, though they often stated that these plans required coordination with their respective counties.” This may indicate an inclination to centralize composting into larger-scale commercial facilities beyond city limits.

The report concludes there is a lack of general understanding among planners of “the full lifecycle of compost,” especially at the city level — a knowledge gap that PFL’s Planning for Compost guide seeks to address.

Planning For Compost Guide

PFL’s Planning for Compost guide drives home the myriad benefits of small- and medium-scale decentralized composting for communities. These types of operations are easier to site and more economical to stand up because they take less space and are often “less technology-fancy” than larger scale commercial composting facilities. Importantly, PFL sees decentralized composting — community composting, on-farm or in-park composting — as key to shifting the mindset of planners and their communities from composting as waste management to composting as bioresource management. Keeping composting and compost use local helps community members experience the “multiple and interrelated benefits of compost” for themselves. “Compost is a uniquely valuable bioresource because its creation and application can simultaneously support multiple goals,” notes the guide, appealing to planners charged with balancing often competing interests.

The guide includes specific steps for planners to consider composting in updates to plans, ordinances, and support for projects in their jurisdictions. The steps are described in detail and available in checklist form for easy use:

Step 1: Assessing Community Needs & Resources — Assess types, volumes and locations of available feedstock, best options for processing, and where there’s demand for compost and potential for end use in order to “tailor the scale, locations, and priorities of composting operations and finished compost products to the needs of a community.”

Step 2: Evaluate Key Considerations — The list includes feedstock accessibility (including consistency or seasonality, ownership of feedstock), stakeholder support (which might be greater for smaller, decentralized sites rather than large commercial), compost end use/application (looking beyond the scope of waste diversion to plan for “place-based bioeconomies” with adjacent industries).

Step 3: Utilize Existing Planning Tools to Support Composting Programs —Tap into zoning codes and municipal ordinances allowing for certain types of composting without the permitting process of commercial facilities, supporting local composters and markets through funding opportunities, public-private partnerships, and prioritizing local compost products to fulfill procurement requirements.

Step 4: Consider Community, On-Farm and In-Park Composting — Costs associated with large-scale, centralized composting infrastructure have been identified as a significant barrier to meeting SB 1383 diversion requirements. Small-to-medium, decentralized operations offer an alternative.

Step 5: Improve Overall Circular Compost Planning Frameworks — Focus on “compost as resource management, connecting urban and rural nutrient loops using compost as a soil amendment” in the underutilized agricultural market.

PFL has a strong vision of planners as connectors and advocates for composters and end market development. “A planner advocating for a composting site can often be the difference between successful implementation and a failed project,” states the report. “In addition to updating planning documents to align composting goals with implementation opportunities, planners can provide direct support for aspiring composters by adjusting municipal zoning codes, setting up funding opportunities, and facilitating collaboration between stakeholders.”

Data Highlights

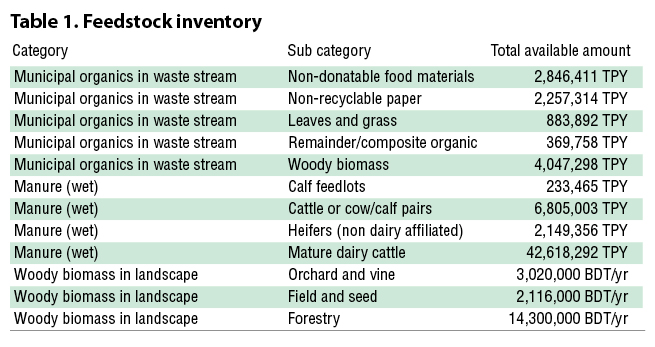

The final piece of PFL’s new suite of resources is a compilation of data estimating volumes of available feedstock from various sources in California and the current throughput of existing composting operations. “CalRecycle keeps tabs on what’s being recycled, but not what’s not being recycled and might be available for composting,” Cain notes. “The state hasn’t prioritized tracking available feedstock materials, but hopefully this project will highlight the importance of that kind of initiative.” She adds that the data don’t show the full extent of potential feedstock available due to a lack of standardized reporting at the county level.

Dairy composting is especially challenging to estimate as it is hard to determine how much of the generated material is already being recycled within agricultural settings. Cain relied on the California Alternative Manure Management Program’s list of past grant recipients to determine where composting of dairy manure is taking place, and then estimated volumes based on heads of cattle per USDA specifications. Dairy composting and community composting are both exempt from state permitting.

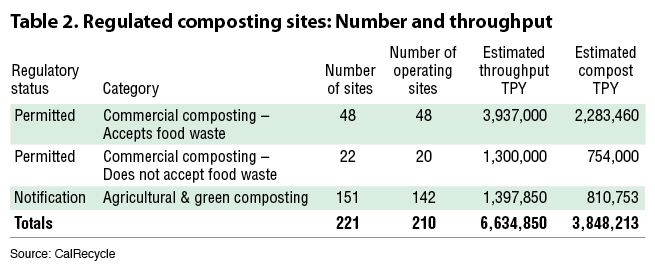

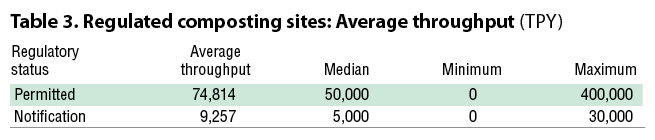

Table 1 describes the compiled estimates of municipal solid waste organics, confined cattle manure, and woody biomass. Data from Table 1 comes from various sources, including CalRecycle, State Water Resources Control Board, University of California at Davis, and others noted in the original spreadsheet from PFL, California Feedstock Inventory 2024 (Public).

Table 2 and Table 3 describe the number and throughput of regulated composting facilities and the average throughput of regulated composting facilities, respectively. Data for Tables 2 and 3 come from CalRecycle. More details are available in the spreadsheet from PFL, Compost Sites Throughput & Creation (Public).

PFL made its feedstock/capacity compost map live on its website in mid-September. The methodology provides more information on map layers, data sources, and PFL’s data collection process.

Next Steps

Cain is watching for the effects of another new state law: Making Conservation a California Way of Life, a regulatory framework adopted by the State Water Resources Control Board in 2024, effective January 1, 2025. The regulation sets customized water use objectives for urban retail water suppliers (not individual households or businesses). Cain sees potential for compost use to help jurisdictions comply with new water efficiency standards, especially in converting to “climate-ready landscapes” that, according to the regulation text, are better able to “weather more extreme conditions, save water, reduce waste, nurture soil, sequester carbon, conserve energy, reduce urban heat, protect air and water quality, and create habitat for native plants and pollinators.” A critical next step for PFL is to “highlight the connection between compost and water — both water savings and improved water quality,” says Cain.

The cyclical compost planning process includes local use of compost for soil-building and ecological improvement. Photo courtesy of UC Merced

PFL hopes to continue creating spaces for planners to come together with community and land-management stakeholders across California to educate and support jurisdictions in incorporating compost creation and application into planning documents in order to realize the full suite of benefits for communities — while meeting the requirements of SB 1383. So far, the potential of compost use to mitigate hazards such as flooding, drought and wildfires has generated the most excitement. SB 1383’s procurement requirement was “well-intentioned to stimulate markets,” says Cain, but many city and county planners and leaders aren’t familiar with compost uses beyond growing food. They need ideas, and “permission to be creative and expansive” in helping facilitate compliance and market creation in the context of a local community’s climate and resilience goals.

Juliana Beecher, a Contributing Editor to BioCycle, is a former ORISE Research Fellow with the U.S. EPA’s Office of Resource Conservation and Recovery. She works as a consultant based in Portland, Maine, focusing on bringing the food waste perspective to broader food systems conversations and efforts to build a more resilient food supply chain.