College students work with campus dining services to recover prepared hot and cold food and deliver it to food pantries and shelters.

Molly Farrell Tucker

BioCycle January 2013, Vol. 54, No. 1, p. 35

Students are encouraged to get engaged in the food donation program, such as using extra meal credits to purchase packaged snacks (top). The snacks are put into bags (above) and delivered with the prepared food.

“In the first weeks, students were recovering 150 to 200 pounds of food a day,” recalls Ben Simon, one of the founders, who is a government and politics major at UMD. “Every night of the week, a different student group on campus would spend an hour recovering food from the dining halls and donating it to shelters in the D.C. area.” By the time the 2011-2012 year was over, the group had donated 30,000 meals to D.C.-area shelters.

Part of the increase in food recovered came from UMD’s basketball and football games. “We get massive amounts of leftover concessions food including hotdogs, hamburgers, pretzels, fries and occasionally crab cakes,” according to a write-up on the FRN@UMD website. “From a single basketball game, on New Year’s Eve 2011, we donated 727 meals!”

Ben Chesler, a friend of Simon’s, launched FRN_@Brown at Brown University in Rhode Island in November 2011 with four fellow students. Within a few weeks they had collected their first few hundred pounds of food. “We recovered over 6,000 meals the first year, and 15,000 pounds of food so far,” says Chesler. Students can use extra meal credits to purchase packaged snacks for donation.

Growing The Network

In January 2012, students from four colleges met to grow the Food Recovery Network, with a mission of creating food recovery programs on every college campus in the country. “We did some research and found that 75 percent of colleges had no food recovery program and were still throwing all of their surplus food away,” notes Simon. In addition to UMD and Brown, FRN joined with two existing food recovery programs, Bare Abundance at the University of California, Berkeley and Food Rescue at Pomona College. Since then, seven more FRN chapters have been formed at the University of Texas, Austin; University of Michigan; Rhode Island School of Design; Providence College in Rhode Island; Scripps College; Harvey Mudd College; and Claremont-McKenna College in Claremont, California. Close to 80,000 meals were delivered in total in 2012.

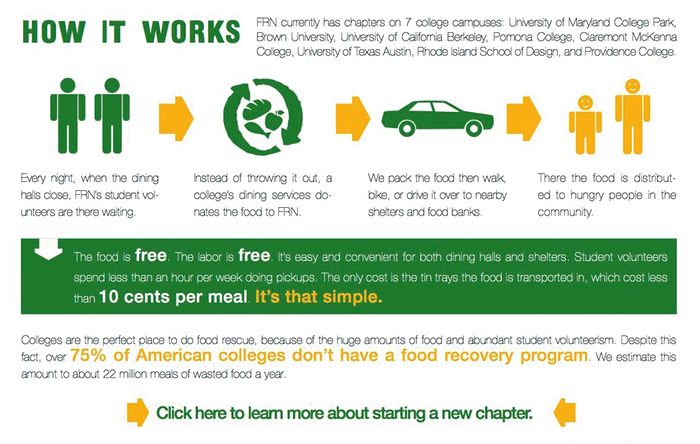

Infographics on the Food Recovery Network website (www.foodrecoverynetwork.org) highlight the donation program and help educate and recruit students to get involved.

Different chapters use different methods to keep the food hot or cold while it is being collected and distributed. “Some freeze it on site, and then deliver the frozen food,” he adds. “Others deliver the food straight to the recipient organizations from either the steam table where it is being kept hot or refrigeration units where it is being chilled. We’re usually able to keep the time in the Food Temperature Danger Zone (41°-135°F) to less than one hour to minimize food safety risks associated with pathogen growth. The federal government recommends two hours as a time limit.” Simon says that FRN is in the process of purchasing insurance to deal with liability issues relating to students driving to deliver the food or food safety.

Most FRN chapters shut down over the summer. “We arranged for a local shelter to pick up food once a week at Brown, but there weren’t students coordinating the program,” says Chesler.

Prepared food is delivered in aluminum trays to the shelters and food pantries. Chapters use different methods to keep the food hot or cold while it is being collected and distributed.

The $500 seed funding comes from a $15,000 grand prize that FRN was awarded in July 2012, as the winner of the Banking on Youth Competition sponsored by Ashoka’s Youth Venture and the Consumer Bankers Association. FRN was one of 180 social entrepreneurship programs and projects competing for the prize. The seed funding can go toward purchase of reusable aluminum trays to transport the food, instead of the one-use trays that some FRN programs have. “Our UMD chapter has successfully transitioned largely to reusables, saving money and helping the environment,” notes Simon. “One of the reasons we want to give chapters grants is for smart, sustainable investments like reusable trays.”

Some of the $15,000 is being used to create new marketing materials for FRN, which recently was awarded status as a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. “Donations made to us are tax-deductible, and we’re eligible for major foundation funding, including the $120,000 per year free advertising we just got from Google,” he adds. “For-profit colleges can also claim an enhanced deduction on their tax returns by donating surplus food to the FRN program.”

Simon plans on graduating from UMD in December 2013. “I have already passed off leadership of the UMD chapter to the next generation of leaders, who have continued to grow the program. We always work to bring in fresh new leaders to, especially underclassmen, to ensure long-term sustainability.”

Molly Farrell Tucker is a Contributing Editor to BioCycle. To learn more about the Food Recovery Network, visit www.foodrecoverynetwork.org.