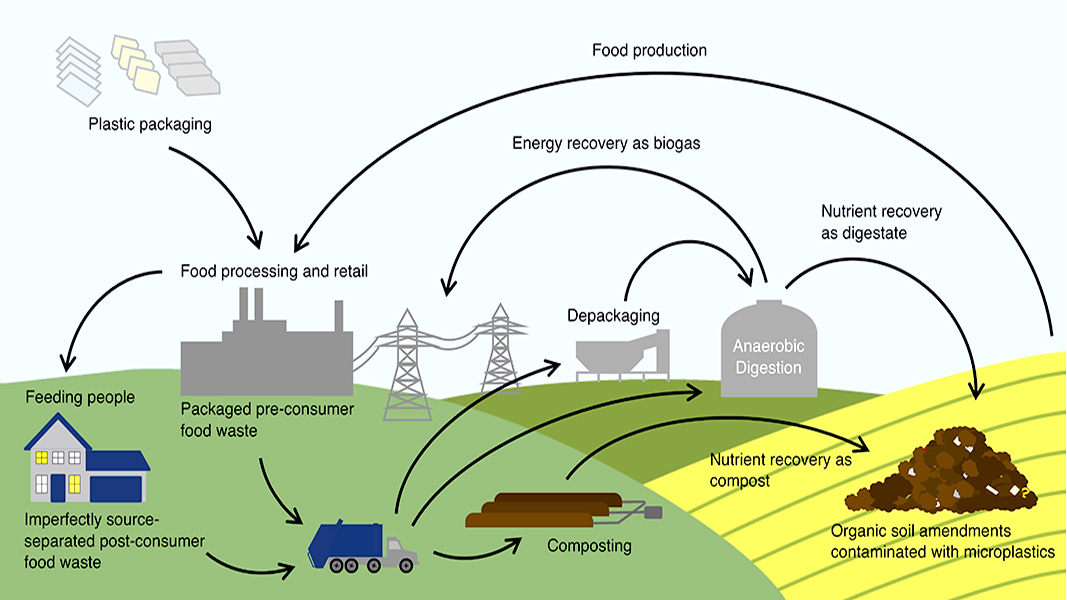

Top: Illustration courtesy K.K. Porterfield et al.

In December 2019, a Universal Recycling Stakeholders Group meeting organized by the Vermont Agency of Natural Resources began with a presentation and discussion about food waste depackaging equipment. At the meeting, some participants expressed concerns over microplastics contamination in soil amendments derived from food waste that is mechanically depackaged. Subsequently, an interdisciplinary team at the University of Vermont (UVM) initiated research related to microplastics. The first step was a systematic literature review that identified microplastic contamination (plastic particles <5 millimeters (mm)) as “a near ubiquitous challenge” in organics recycling. In a policy paper released in early February, “Microplastics in Composts, Digestates & Food Wastes,” the authors of the UVM literature review — Katherine Porterfield, Sarah Hobson, Deborah Neher, Meredith Niles and Eric Roy — concluded that “no technology or processing strategy is inherently free of contamination risk.”

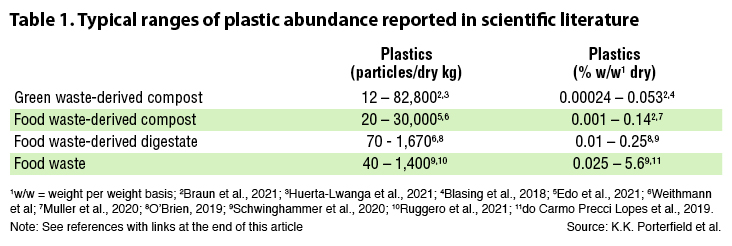

The literature review, summarized in the policy paper, found that reported plastic abundance varies widely both within and between studies in large part due to a lack of standard methods for measuring microplastics in complex organic materials (e.g., composts and digestates). This complicates comparison among studies. For example, write the authors, “researchers more frequently measure microplastic contamination in units of particle count per dry weight of material, however a smaller number have reported values on a weight per weight (w/w) basis, as seen in Table 1. … Conversely, the most common methods for identifying microplastics (light microscopy and Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy) generate count per [dry] weight values. There is currently no consistent method to convert microplastic abundance between count per [dry] weight and w/w units, making the translation of scientific results into regulation challenging. Enforcement of regulatory thresholds defined by w/w units will require advancements in methods. Furthermore, plastic size classes included also vary widely across studies. Methodological differences likely exert a strong influence on measures of microplastic abundance and underscore the need to develop standard methods for measuring microplastics in the environment.”

The authors add that currently there is a “mismatch between existing regulations and scientific approaches for measuring microplastics. Existing regulations and ecotoxicity studies typically delineate thresholds or toxicity levels on a w/w basis.” Their preliminary data for depackaged food wastes and digestate in Vermont fall within the range of values reported in Table 1 (count per weight basis). A preprint of the literature review findings, “Microplastics in composts, digestates and food wastes: A review,” can be downloaded at this link.

The policy paper also addresses legislation introduced in the Vermont General Assembly in early January 2022. H. 501 — an Act to relating to contaminant standards for residual waste, digestate, and soil amendments — originally proposed that residual waste, digestate, and soil amendments shall not contain more than 0.5% by dry weight of physical contaminants greater than one millimeter and that no more than 20% by dry weight of the 0.5% by dry weight of physical contaminants shall be film plastic greater than one millimeter.” In late January, a different bill, SB.282 was introduced in the Vermont Senate. SB.282 proposes to establish a moratorium on the certification by the Secretary of Natural Resources of food depackaging facilities until the Secretary reports to the Vermont General Assembly regarding the operation of food depackaging facilities and adopts rules for their operation. On February 23, The House Natural Resources Committee voted to advance a new version of H.501 derived from SB.282 with some amendments. BioCycle will be tracking these legislative activities in Vermont.

Visible plastic contamination in (A) organic municipal solid waste compost windrows prior to screening (credit: E.D. Roy, S. Asia), (B) screw-press separated solid digestate from codigestion of dairy manure and food waste (credit: E.D. Roy, United States), and (C–F) putative microplastics found in food waste digestate (Image courtesy K.K. Porterfield et al.).