BioCycle August 2011, Vol. 52, No. 8, p. 43

BioCycle August 2011, Vol. 52, No. 8, p. 43

In 2000, Cedar Grove Composting in Washington State began compostable product testing to ensure biodegradation in its system. A decade later, the company is licensing its own line of approved items.

Dan Sullivan

AS the city of Seattle’s official organics recycler processing about 90,000 tons of material annually, Cedar Grove Composting has faced many challenges. The pioneering company has met these challenges head on since opening for business in 1989 in Washington State. This includes taking on what’s become an increasingly complex issue for commercial composters – managing an escalating number of so-called ‘compostable’ products, some which break down better than others.

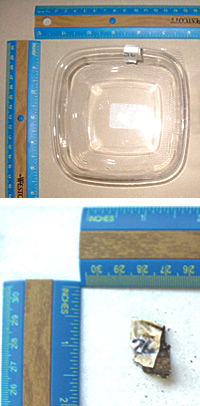

In 2000, Cedar Grove – one of the first commercial composters in the country to process postconsumer food waste – began testing products for compostability using the company’s own standards established to mesh with its aerated static pile 8-week-cycle composting method utilizing the GORE Cover System. That was followed a decade later by Cedar Grove’s Brown Line program branding compostable products with the company’s logo and signature brown stripe. Licensing is available for a fee to compostable serviceware manufacturers whose products have passed Cedar Grove’s compostability test. Officially trademarked in January 2011, Brown Line gives Cedar Grove an additional revenue stream and community compost facilities a way to visually identify products as compostable. As Seattle’s organics recycling program bears out, being able to identify compostables is only part of the equation.

“It was about maintaining our product quality and making sure we’re reducing contamination and providing a system where people can understand what we accept in our bins and what we don’t,” says Jerry Bartlett, Chief Environmental & Sustainability Officer at Cedar Grove. Both commercial and residential clients in Seattle can save significantly on their trash bill if they source separate organics.

Cedar Grove has now approved more than 700 products from dozens of vendors for composting at its facilities in Maple Valley and Everett. These include: deli bags and containers, napkins, bakery boxes, deli sheets, plates, bowls, drink carriers, portion cups, clamshells, food trays, straws, coffee sleeves, food-service gloves, cold cups, hot cups, utensils, meat trays and takeout food, yard and compostable waste bags as well as other miscellaneous items.

The company provides commercial clients, and the private haulers who service them, with an expanding list of compostable products that can be included in the compostables stream separated out for collection and delivery to its facilities. Since July 2010, any food establishment within Seattle’s city limits serving single-use/to-go items must do so in containers that are either recyclable or compostable. Passing “compostable” muster means the products must appear on Cedar Grove’s approved list. Seattle residents may only include compostable containers for collection in their compostables bins if they bear the Brown Line logo. Brown Line items are typically distributed to food-service outlets in Seattle and the greater Pacific Northwest through commercial vendors and are not readily available for retail purchase. “We started our testing program in lieu of the national [American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) D6400] standard, which we didn’t believe at the time worked,” says Bartlett. Now, he says, Cedar Grove has become a major player in helping to improve that standard.

While composting is not mandated in Seattle (except for yard trimmings), the city’s comprehensive signage – with pictographs, color-coding and as many as 14 languages – might lead residents to draw a different assumption. “If you live in Seattle, you might think it’s mandatory,” says Bartlett. “When customers get a flier at home, food is listed as going in the compostables bin. But if you actually threw it in the garbage, you wouldn’t get in trouble.” (Recycling, on the other hand, is required by law.)

Residential yard trimmings and food scraps go into one bin. One hiccup in the system is that most of the to-go cups and other single-use packaging going out of Seattle food establishments are not Brown Line products, so even though they are all certified as “compostable” by Cedar Grove, the company will treat them as contamination if they end up in residential compostables bins. That means they go to the landfill. Despite a few such bumps, Cedar Grove’s certification and licensing program does an admirable job encouraging the end-of-life scenario for which compostable products were intended.

THE ORGANIC DILEMMA

A new challenge for Cedar Grove’s compostable products initiative is recent clarification by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Organic Program (NOP) stating that bioplastics are not permissible in compost destined for certified organic farms because they contain synthetic materials that have not been approved for organic production. “I think the big unknown at this point, the big shift nobody expected, is the National Organic Program’s effect on composting of all these products,” says Bartlett. “More composters are getting on the bandwagon where they don’t want to accept any of them because of the NOP [policy on bioplastics].”

Some municipal food waste composting initiatives are becoming stalled, Bartlett notes, particularly in areas where composters sell heavily into the certified-organic market. “Some manufacturers have called and asked us to convince other composters to take these products,” says Bartlett, adding that if he were just getting started in today’s climate, he’s not so sure he’d bother with them either. “The fact that we are pioneers in the industry and that our wagon ended up where it is doesn’t mean it’s where we wanted it to be.”

Bartlett was part of a contingent of stakeholders that went to the National Organic Standards Board (NOSB) when it met in Seattle in April asking that it consider all compostable products that meet the Biodegradable Products Institute (BPI)/ASTM standards for compostability as acceptable for organic production. (The NOSB maintains an evolving list of allowable synthetics which it considers on a case-by-case basis.) “The Board’s response was, ‘No, we don’t have a way to deal with ASTM. We have to look at each product [ingredient] individually,'” Bartlett reports.

The nonprofit Organic Materials Review Institute (OMRI) was founded in 1997 by a partnership of certifiers, food industry representatives and organizations with an interest in organic farming. OMRI reviews brand-name input products for compliance with the NOP standards and is well acquainted with both the USDA program and its guiding documents and protocols. “Just because the NOP said ‘no’ to compostable plastics doesn’t mean that WORC (Washington Organics Recycling Council) or BPI – or anybody, really – couldn’t petition the class of compostable plastics that meet ASTM standards,” says OMRI Program Manager Lindsay Fernandez-Salvador. “There are examples on the National List that allow for a class of synthetic materials – for example, excipients for livestock drugs – and I personally think this could be the best approach for a group of stakeholders to come together and share the burden of petitioning this class of compostable materials. It would also help drive the development of more products that are certified to BPI [Biodegradable Products Institute] and ASTM standards.”

Bartlett is uncertain that approach is viable. “A class of products is not the same as a testing method,” he says. “Similar chemical characteristics in a class is one thing, but you can put many things in bioplastics and still pass ASTM testing protocol.”

Stakeholders including BPI and some of its member bioplastics manufacturers are deciding what approach to take next regarding the NOP and say it’s too early to comment on what form that strategy might take. If the strategy involves getting the NOP to change its policy and allow for approval of a testing method versus individual ingredients, then getting a particular testing method approved, that could be a very long row to hoe, Bartlett says. For now, he predicts, “We’re going to see more and more of these products not go to composting – they’re going to be separated out when they get to the facility. Or composters will have to have two streams and make an organic versus a nonorganic product, which is what we’re doing.”

Besides making their way into customers’ hands through local eating establishments, Cedar Grove Brown Line products may also be found at venues such as Safeco Field, home of the Seattle Mariners (see “Take Me Out To The Windrow,” December 2010), where the compostable serviceware has helped to achieve 82 percent waste diversion. Brown Line might also be discovered across America, just as one BioCycle staffer did at a sidewalk café during a recent visit to Chicago. “Once a product has passed our tests, the manufacturer can apply for a licensing agreement to use the brown logo, and sell that product anywhere,” explains Bartlett. He adds that it probably won’t have the recognition or be as easily identified by a composter in Chicago or Los Angeles as it is in the Pacific Northwest.

Cedar Grove’s next big push of the innovation envelope is the planned installation of a BIOFerm high-solids anaerobic digester to convert food scraps, yard trimmings, soiled paper and other feedstocks into energy before composting. Only the second U.S. site to implement the dry digestion technology – right behind the University of Wisconsin at Oshkosh (a site on the BioCycle Renewable Energy Conference tour on November 2) – the project stands to help the facility manage odors as well as save on its utility bill. Permits for the project were resubmitted this summer and work will begin once they are approved.

What won’t be going into the digester is Brown Line or any other compostable serviceware. “We’re going to have to pull it all out,” says Bartlett, explaining that the products do not digest, nor do they produce biogas. “It’s all appropriate to be composted, but we’re not putting it in the digester.”

August 16, 2011 | General