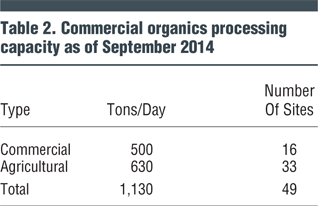

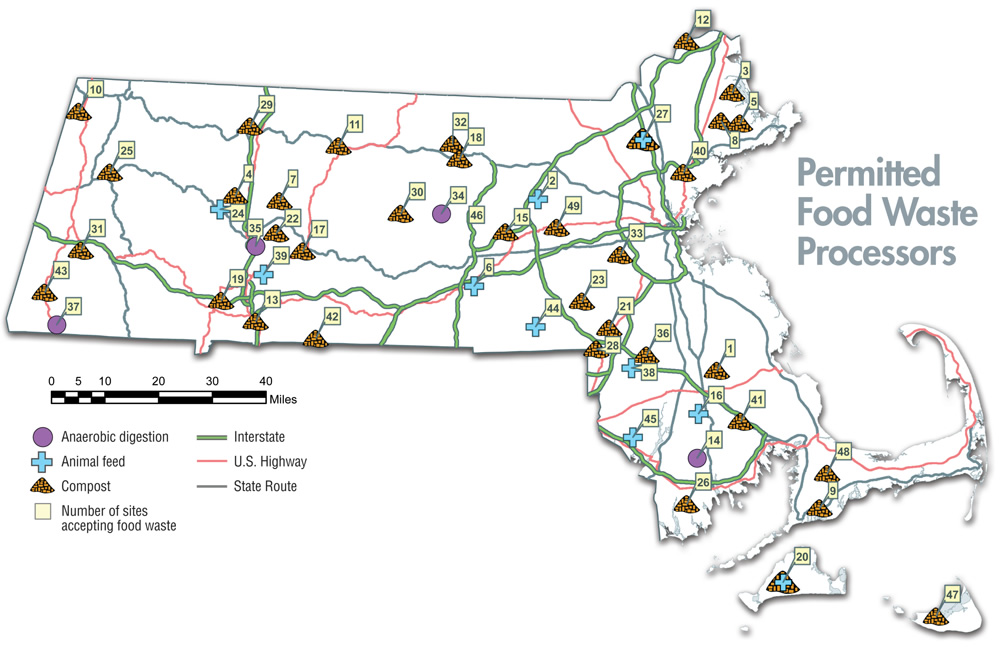

The state’s ban on disposal and combustion of commercial organics became effective October 1, 2014. Currently, approximately 49 permitted food waste processors have a combined capacity of 1,100 tons/day. Part I

Zoë Neale

BioCycle October 2014

With the much anticipated Massachusetts landfill and combustion ban on commercial organic waste in effect as of October 1, 2014, all eyes are on the state and whether there is adequate processing capacity. Massachusetts is the first state to impose a disposal ban on all large commercial and industrial food waste generators (defined as producing 1 ton or more a week) regardless of proximity to a processing facility (see “Implementation Realities of Organics Ban in Mass-achusetts,” April 2013). This article discusses the evolution of the processing infrastructure over the last 18 months as well as implementation challenges that remain as the ban goes into effect.

The concept of banning organics from the waste stream originated in the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection’s (MADEP) “Beyond 2000 Solid Waste Master Plan: A Policy Framework.” This plan explicitly recognized the challenge of solid waste management that Massachusetts is confronting due to significant reduction in available landfill capacity through 2020. The plan very clearly outlined the critical role of organics diversion in reaching the state’s waste reduction goal while also acknowledging the constraint of limited in-state organics processing capacity.

The Beyond 2000 Plan laid the groundwork for applying the same ban framework to commercial organics that had been established in 1990 for other recyclable and/or compostable materials. However, it included a major caveat regarding the shortfall in processing capacity, which was addressed in MADEP’s 2010 Master Plan via a strategy to revise the state’s organics management rules. Two primary goals of the 2010 Plan (which was finalized in April 2013) are 1) Diversion of an additional 350,000 tons/year of organic material from disposal and 2) Have 50 MW of anaerobic digester electricity generation by 2020. Regulations were promulgated in November 2012 that explicitly excluded processors of source separated organics from site assignment (a requirement that any new or expanded solid waste facility obtain a site suitability determination from MADEP before siting approval by the local Board of Health), therein creating a clear pathway for organic waste processors to build and site new capacity in the state (see “Massachusetts Sets The Table For An Organics Ban,” December 2012).

Available Organics

The commercial organics disposal ban was intended to incentivize development of private, commercial scale anaerobic digestion (AD) and composting facilities by creating guaranteed feedstock access and an increase in demand for processing. Concurrently, the state also announced an aggressive goal to site one to three stand-alone, large-scale anaerobic digesters on state owned property by 2014. The plan was for public/private partnership development of facilities that generated 1 to 3 MWs, and processed 20,000 to 50,000 tons/year of organic material utilizing long term license or lease agreements. The state interagency team that partnered to implement these goals identified three properties for feasibility studies: Department of Corrections facilities in Norfolk and Shirley and the wastewater treatment facility at University of Massachusetts, Amherst. Although feasibility studies were conducted and completed in 2013, RFPs have yet to be issued for development on these sites.

A frequent question is the accuracy of the assumptions that MADEP has utilized when characterizing the total amount of industrial, commercial and institutional (ICI) organics in the waste stream and, more importantly, how “accessible” those materials are to agricultural and commercial processors. The agency has estimated that more than one million tons of commercial and institutional food waste are generated annually from all commercial and industrial sources, with the ban applying to 1,700 generators (versus original estimates two years ago of 3,000 businesses and institutions subject to the ban). The MADEP has estimated that currently diversion programs are in place at 1,400 sites, including 350 supermarkets. Although there are some smaller generators in that group, it is clear that many of the larger organic waste generators have already found a “home” for their organics, leaving much less available feedstock for developers of larger scale projects.

This situation — i.e., that by MADEP’s own estimate, the majority of ICI organic waste is already being diverted — has played heavily into developers’ due diligence when making their assessment of project feasibility in the state as the proverbial “low hanging fruit” has already been picked when it comes to sourcing feedstock. In other words, what is left in the market can be characterized as a high percentage of postconsumer commercial waste rather than preconsumer or industrial streams which tend to be cleaner, more continuous in terms of volume and often more homogenous. Essentially, with the ban in effect, rather than asking “Where are all those organics going to go?”, anecdotal evidence from discussions with state officials, haulers, processors and developers, points more clearly to the question of “Is there enough available and desirable food waste to feed a large-scale AD facility?”. The answer is in the amount of infrastructure development in the state since the ban was announced in 2012 and what is built over the next several years. Part II of this article will discuss the latter.

One of the most significant challenges for MADEP is in the form of effective enforcement of the commercial organics ban. This ban differs from the previous 14 solid waste bans (which include lead batteries, leaf and yard waste, metal and glass, and recyclable paper) as it is a conditional ban, i.e. it only applies to generators that produce one ton or more a week, not smaller commercial generators or the residential sector. This distinction requires the addition of an incremental layer of oversight on the tip floor as not all organics from all sources are considered banned materials. At the center of enforcement are the haulers that are required to track down, inform and correct customer behavior or bear the cost of noncompliance letters and potential fines. The fact that the “onus” is on the transporter of the substrate rather than the generator continues to be a source of consternation for the haulers and the solid waste facilities. One other challenge to effective implementation is demonstrated by the fact that in 2013, 40 percent of MSW was composed of already banned materials. This large percentage does not include food waste but points to the difficulty the solid waste system and the state have in enforcing the multiple bans already in place.

The primary food waste composters in the greater Boston area include Brick Ends Farm in Hamilton, Massachusetts. Photo by John Sweeney

Food Waste Processing Site Development

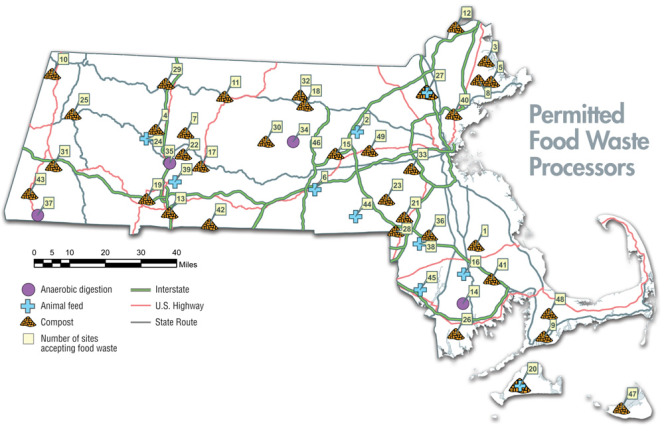

Currently in Massachusetts, there are approximately 49 permitted food waste processors (versus around 30 a year ago) with a combined capacity of approximately 1,100 tons/day (see map on p. 19). The majority (by number) of sites are farm-based, smaller scale composters. Farms that engage in composting activities qualify for a conditional exemption (310 CMR 16.03) under MADEP’s regulatory framework, assuming the facility is receiving less than 105 tons/week of vegetative and food material. As such, the farm-based composters are exempt from MADEP permitting requirements and are only required to register with the Massachusetts Department of Agriculture Resources (MDAR).

Seven processors in the state are currently permitted to receive more than 15 tons/day (tpd) (105 tons/week). These larger processors include three dairy farm-based anaerobic digesters (Pine Island Farm, Jordan Farm and the state’s newest, Barstow’s Longview Farm (see “Building Farm and Food Scraps Digesters, June 2014), three processors that cocompost with wastewater biosolids (WeCare Environmental in Marlborough, Waste Options on Nantucket and Fitchburg Westminster Compost in Westminster) and one commercial site that has historically only accepted industrial (e.g., food processing), not commercial, food waste (Mass Natural in Westminster). The primary food waste processing outlets for the Greater Boston area remain WeCare, and two composters — Rocky Hill Farm in Saugus and Brick Ends Farm in Hamilton. Of the 49 processors, 16 are commercial (12 which are permitted for >15 tpd), 25 are agricultural (22 permitted for 15 tpd) and eight are animal feeding sites.

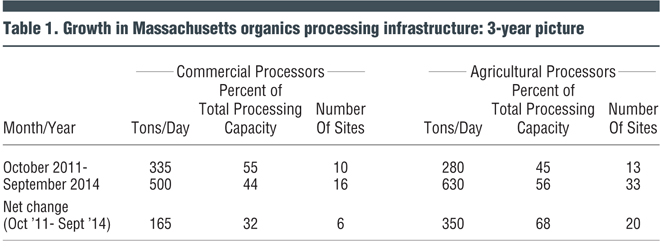

Since October 2011, 26 agricultural, commercial and animal feeding organics processing sites have been “added” in Massachusetts, increasing total processing capacity in the state from just over 600 tpd to over 1,100 tpd (over 250,000 tons/year), an increase of almost 80 percent. (“Added” is in quotes because the eight animal feeding locations have been operational for many years but MADEP only recently included them in its processing capacity “count.”) About 70 percent of that “new” capacity represents farm based agricultural processors rather than the commercial sector. This includes 200 new tons/day combined at the two new dairy farm digesters, both of which are over 100 miles from downtown Boston. At this point, over 55 percent of the organics processing capacity in Massachusetts is at facilities that are registered with MDAR, and not permitted by MADEP. (In some instances these registered sites often receive and process far less than the standard 15 tpd.) Table 1 summarizes the change in commercial and agricultural organics processing infrastructure in Massachusetts from 2011 to 2014. Table 2 summarizes the totals for each sector.

Commitment By The State

With the launch in 2011 of the Clean Energy Results Program, Massachusetts announced significant state programs to further development of organics processing capacity including: 1) Encourage municipal expansion of existing composting and siting of new operations; 2) Develop AD facilities on state property (discussed above); 3) Encourage new private development or expand existing organics management capacity; and 4) Assess and support development of on-site food waste management solutions.

In Massachusetts, farm based composting has always played a major role in the organics processing landscape. According to MDAR, there are approximately 80 farms in the state currently composting leaf and yard waste, with around 25 also accepting food waste. The exemption from DEP permitting is a critical component to ensure the continuation of the critical role that Massachusetts farmers play in the overall processing landscape and in reaching the state’s goal of developing 350,000 incremental tons per year of organics diversion. It is not possible for the state to reach its organics diversion goals without farm-based participation although farmers will not invest in composting at the expense of losing important farm tax exemptions under Chapter 61A of the Massachusetts tax code.

In terms of anaerobic digestion, the state has funded multiple feasibility studies over the past two years for public entities interested in locating AD within their towns or using existing wastewater treatment facility digesters to accept food waste. Towns that have received state money to conduct these studies include Lexington, Hamilton, Milbury, Fitchburg, Brockton, Greenfield, Barnstable, Easthampton, Ayer and Plymouth. Two wastewater treatment facilities received funding: Massachusetts Water Resources Authority and Greater Lawrence Sanitary District. In addition, there has been a study funded at the Franklin Park Zoo for composting with heat recovery. Of these studies, five towns have either issued Requests for Proposals or have brought the idea to public hearing. None have led to a project being developed.

Construction funds (typically grants for $400,000) have been awarded over the past two years to the Commonwealth Resource Management Corp., NEO Energy (2 grants for different locations), Greater Lawrence Sanitary District, MWRA ($200,000 for modification of facilities to enable codigestion), Ken’s Foods (on-site CHP facility), Pine Island Farm ($281,000 to add a second generator to existing system) and BGreen Energy/Barway Biogas ($400,000 for construction of digester and CHP system).

Massachusetts Governor Deval Patrick is leaving office in January 2015, which may have implications for the regulatory framework of organics management in the state. The processing infrastructure is overseen jointly by the MADEP and MDAR, which are both overseen by the Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs (EOEEA), a cabinet level position appointed by the governor. With a new administration, there is little doubt that there will be a new head of the EOEEA as well as a distinct possibility that the commissioners of both MADEP and MDAR will be replaced. This almost certain transition of leadership of EOEEA, MADEP and MDAR creates the possibility of programmatic changes regarding organics management and uncertainty for developers of processing facilities in the state.

However, through the multiyear process of creating and promulgating organics diversion regulations and goals, Massachusetts has proven itself to be at the forefront of the quickly evolving commercial organics marketplace. Although capacity developed has not been in the form of large scale, merchant AD facilities that state officials were envisioning, there continues to be a high level of interest and innovation at all scales of development.

Zoë Neale is founder of Mass Organics Solutions, an independent consulting firm specializing in helping companies navigate the organics market in the Northeast. She is a Contributing Editor to BioCycle.