King County, Washington is addressing the consequences of misinformation about biosolids by creating a brand to help communicate the facts in a consistent way.

Katrina Mendrey

BioCycle June 2013, Vol. 54, No. 6, p. 21

King County biosolids transport trucks promote Loop, featuring scenes of flowers in bloom, Washington forests or wheat fields.

Most of the trucks head toward two of King County’s largest biosolids customers, Boulder Park, Inc. and Natural Selections Farms. About 80 percent of the Class B product is then distributed and applied by these farmer-owned companies to agricultural crops on the east side of the Cascade mountains. Approximately 15 percent goes to commercial forestland managed by Hancock Natural Resource Group and the Washington State Department of Natural Resources. Up to 5 percent is used by a local composter, GroCo, Inc., which manufactures the only publicly available product containing Loop. GroCo makes a Class A product consisting of biosolids composted with sawdust.

So why develop a brand if you already have a market for your product? “One of the goals of this project is to inform the public of the good work we’re doing at King County, and what a great resource biosolids are,” explains Kate Kurtz, Biosolids Project Manager at KCWTD. “If you’ve never heard of biosolids before you’re more likely to believe misinformation from noncredible sources. Correcting and dealing with the consequences of misinformation is one of our greatest business challenges. Creating a brand helps us to get in front of the message by communicating the truth about our product in a consistent way.”

She adds that the Loop brand images on the trucks spark peoples’ curiosity. “They see the logo and want to know what’s inside and where the trucks are going,” notes Kurtz. And this curiosity presents an opportunity for education.

Branding Process

But the trucks are just one piece of the larger branding project King County recently launched to bring new awareness to its Class B biosolids product. The initiative included a new name, messages, website, brochures and an internal training campaign to educate employees on how to communicate the new brand in a consistent way. Central to this process was developing an authentic brand and messages that employees, from wastewater treatment operators to managerial staff within the county, feel could accurately and effectively communicate the product and its benefits to the public. “Our main goal was to come up with a brand and message that was authentic and true, and I think that is what has made our effort such a success and will give this brand longevity,” says Kurtz.

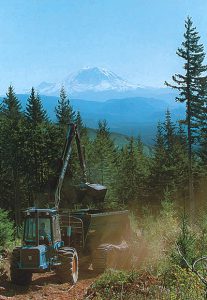

About 15 percent of Loop® goes to forestland application (above); about 80 percent is used for application on agricultural crops.

The firm recommended development of an ingredient brand that could be leveraged and built upon by organizations outside King County. Much like other ingredient brands such as Intel computer chips or NutraSweet, Loop is an ingredient that can stand alone or be an ingredient in another product with its own brand such as GroCo™ compost. Both Weisnewski and Kurtz, however, emphasize that developing a brand is different than having a communications plan. “A brand platform includes brand assets such as name, tagline, logo, as well as mission, values, and promise,” explains Weisnewski. “These assets are action drivers as well as communication tools. They should inform decisions and culture, as well as communications.” In essence, adds Kurtz, the brand is the filter through which all actions, decisions and communications pass, and informs the tone of specific communications tools and outreach.

Before the brand name and image could be developed, Kite worked to gain a better understanding of the product, what was meaningful to audiences, and what the brand needed to achieve. The company interviewed several employees, from plant operators to outreach staff and the division director. Other interviews were conducted with farm and forest customers, GroCo employees and professional gardeners, as well as nurseries in the community with varying levels of knowledge about biosolids. Questions included: What are the top strengths and weaknesses of King County’s product? What do you value the most about the product? “These interviews confirmed that lack of education and understanding was an issue that needed to be addressed as part of the brand development and future communications, but that people who were familiar with the product were raving fans,” says Weisnewski.

Based on these interviews and a competitive review of other local soil amendment products, Kite determined that by developing a brand that could be used to help overcome this education barrier, KCWTD could diversify its customer base for biosolids-based products. In addition, internal interviews revealed that creating a brand that KCWTD employees could be proud of was important to the brand’s success. “Part of building an authentic brand is creating a brand that key players of the organization are in agreement with, and that they will champion,” explains Weisnewski. Information collected during these interviews informed everything from brand name, logo and tagline to the color palette and content used in marketing materials, including brochures, the website, and swag like hats, pens and sticky notes.

Why Loop?

Initially a team of about 20 employees from a cross-section of KCWTD were involved in early brainstorming efforts. Eventually a sub team of 5 staff members was empowered to make the final choices about the brand and messaging development. “Loop” was chosen from a long list of other names provided by Kite and King County employees, including Nutri360, BioBoom and DirtCake. While all of the names on the list highlighted a particular benefit of the county’s biosolids product, Loop won for its ability to communicate the sustainability of the product as an infinitely renewable resource.

The brand is featured in King County’s promotional materials and on its website. The branding consultant recommended an “ingredient brand” approach because Loop can be utilized directly (e.g., on crops) or as an ingredient in another product with its own brand, such as GroCo™ compost (discussed in website example above).

And memorable it is. While there are currently no official attempts to monitor increased public interest, Google analytics for the Loopforyoursoil.com website have shown searches specifying “Loop” in various search engines. This is a good start in terms of brand recognition. Further, demand for samples of GroCo made with Loop was so high at the initial launch of the brand, the county ran out of samples and needed to restock several times. And the Loop trucks are certainly becoming a new Seattle icon. Kurtz was recently contacted by a local author interested in incorporating them into the plot of an upcoming book.

Kurtz’s goal, however, is to more formally quantify these successes with information gathered from the division’s biennial telephone survey. Each survey includes some questions regarding biosolids and perceptions. It was last conducted two years ago before Loop was branded. The upcoming survey will include questions to gauge how public perceptions may have been influenced by the new brand. While the impact on public awareness of this Class B product is still being evaluated, one thing is clear to Kurtz: “Loop has inspired pride in our employees and our customers.” And that’s the true measure of an authentic brand.

Katrina Mendrey is a master’s student working with Dr. Sally Brown at the University of Washington’s School of Environmental and Forest Sciences. She earned her B.A. in Political Science at the University of Montana. After graduation she hopes to continue working in the field of soil science research.