Top: Snapshots of headlines from The Boston Globe

Sally Brown

Sally Brown

Two recent articles in the Boston Globe have helped to fan the flames. The Globe is generally considered a good and solid source of information. From a PFAS perspective, however, it would seem that clicks rather than well-resourced and balanced information is what they are after.

On May 27, 2022, the paper featured an article about Boston’s new city-wide composting program: “Mayor Wu announces new citywide composting program,” written by Dharna Noor. The article detailed the importance of landfill diversion of food scraps. No argument there. It also described how a portion of the collected material will be sent to anaerobic digesters located at the wastewater treatment plant in North Andover, Massachusetts. City officials said that this portion of the collected food scraps will be turned into “clean energy.” It will also, in its treated form, form a portion of the biosolids that the plant produces.

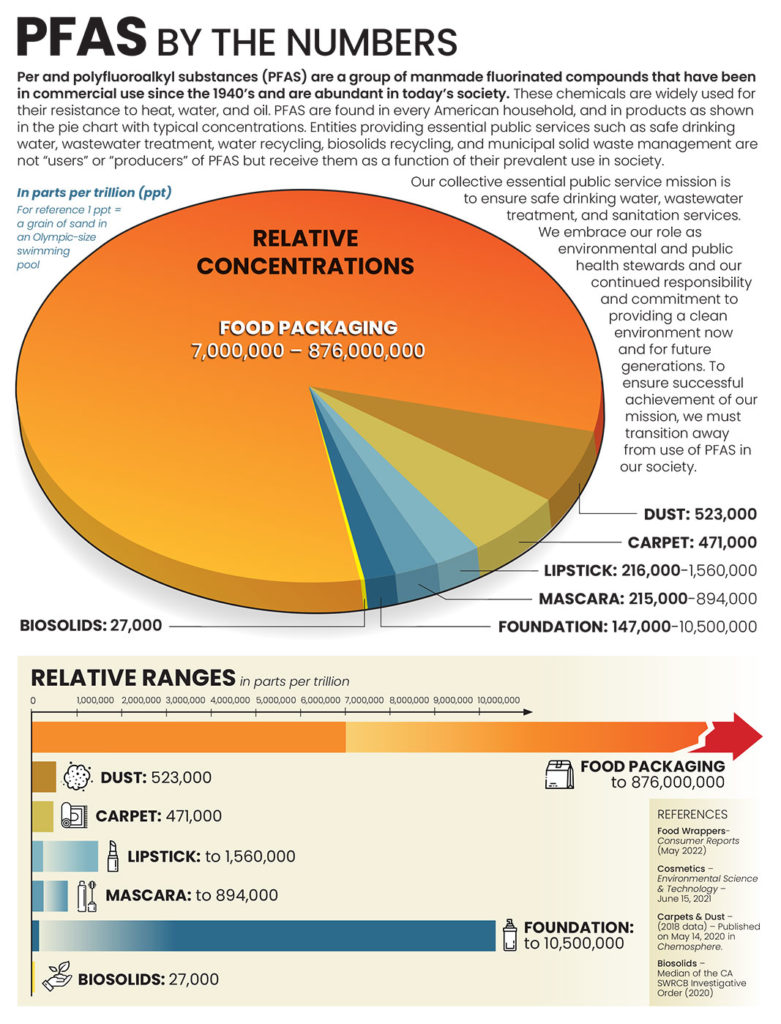

The reporter spent much of the next few paragraphs focused on the biosolids aspect of the plan. Here the author interviewed an attorney who directs the nonprofit Conservation Law Foundation’s Zero Waste Project. This person was their sole source of information on the topic. The attorney pointed out that the food scrap residues would end up in sludge which “can contain heavy metals, microplastics, and PFAS, a carcinogenic forever chemical.” She went on to say that sludge was toxic and can contaminate farmland. What the lawyer failed to mention and the reporter failed to recognize is that we, meaning us humans, also contain all of the above. The figure below, created by the California Association of Sanitation Agencies, illustrates the concentrations of these compounds in various consumer products and biosolids.

An appropriate article would have put that quote in context. Might have done a quick check on Google scholar to see if the concerns were justified. Perhaps even talked to people who do research in the field. She could have looked at the National Academy of Science studies on the topic, or spoken with the treatment plant operators to find out more about the biosolids — their characteristics and how they are used. I have talked to the engineer in charge of the North Andover plant. Turns out that the PFAS concentrations in their biosolids are on level with food scraps compost. The biosolids are pelletized and used in western Massachusetts. Instead, the author went for the click.

PFAS Contamination

The second article was published on July 6. Here the author is David Abel and his headline reads: “When organic is toxic: How a composting facility likely spread massive amounts of ‘forever chemicals’ across one town in Massachusetts.” This article is all about a composting facility in central Massachusetts, Mass Natural Fertilizer Company (MNFC). According to the article, the facility has been in operation for over 30 years and composts a range of organics annually on a 240-acre facility. The author states that the owner of the land is Otter Farm, a subsidiary of Seaman Paper, a 70+ year old paper manufacturer. As a result of PFAS contamination of groundwater, the state is now prohibiting sales of compost from MNFC and saying that the current owners are potentially liable to cover clean-up costs for the land and the groundwater. The Globe article also reported that officials at Seaman have tested their wastewater and have found “no evidence of ‘high concentrations’ of PFAS.” It should be noted that material from Seaman Paper is a compost feedstock.

I have not been to the site, seen analysis of the compost or seen a list of the compost feedstocks over time. I did do a quick search for the Seaman company and found that they have been making paper products, including high quality bonded paper and food service packaging, for decades. They even have a picture of pizza in the box on their website (see graphic at right).

I have also seen data on composts made from food scraps and yard trimmings showing very low concentrations of PFAS compounds. Lazcano et al. (2020) tested a range of commercially available composts and biosolids-based products. The biosolids-based products had concentrations ranging from 9 to 199 parts per billion (ppb). The food + yard waste composts had concentrations of less than 19 ppb. I have no reason to believe that the compost produced within the last decade at MNFC was anything special as far as PFAS is concerned. I have every reason to believe that the paper company, in existence for decades and manufacturing the types of paper known to have high concentrations of the two now banned types of PFAS, did produce residuals that were high in those compounds. Rather than chasing the leads, the reporter for this story chased the clicks.

Sally Brown, BioCycle Senior Adviser, is a Research Professor at the University of Washington in the College of the Environment.