Top: Pod of sea lions in the Puget Sound near the Ballard Locks in Seattle.

Sally Brown

Sally Brown

I live right on the Puget Sound in Washington State, a part of the Salish Sea. The Salish Sea is a magical place where you can routinely find seals, sea lions, orcas, dolphins, Dungeness crab and salmon. This is an area of lots of water or very little, depending on the time of year. We just had the wettest fall on record. I am sitting watching it rain sideways as I write this. This summer we had one of the driest on record. It rains for most of the year except during the months when it doesn’t. Come the end of August, now prime fire season, even I find myself wishing for rain. This wish is tempered by the fact that when the rain comes it doesn’t stop coming for months and months and months.

Map data ©2021 Google

The chemistry of the Puget Sound reflects this mixture of salt and fresh water. The fresh water is lighter and tends to float on the surface of the heavier salt water. Add to this the importance of appropriate levels of dissolved oxygen that keep its inhabitants happy. In these conditions any excess nitrogen can result in depletion of the oxygen. During the increasingly dry summers the reduced flow of fresh water effectively enriches the nitrogen concentration of the salt water, reducing the quantity of available oxygen as the sea creatures use it to take advantage of the nitrogen.

Everybody agrees that the primary source of nitrogen in the Puget Sound is the salt water from the Pacific Ocean. It is highly likely that this problem is going to worsen with climate change; drier summers and wetter winters.

The solution proposed by the Washington Department of Ecology is to ask the municipal wastewater treatment agencies to reduce their nitrogen loading into the Sound. The vast majority of these agencies discharge their treated effluent directly into the Sound. This water does contain nitrogen — not a lot but certainly enough to detect.

If you think about it, imposing tighter restrictions on the treatment plants is the most obvious traditional solution. Regulators can’t control climate change. They can’t control nitrogen (N) concentrations in the Pacific Ocean. Setting limits on N release in effluent is the obvious choice. The problem is that this solution will cost a lot of money. In King County where I live, it would involve building another treatment plant with a price tag of $9 billion to $14 billion. It is also very far from a sure thing that it will make a detectable difference.

Reclaimed Water Fantasy

The same time as this all is reaching enough of a climax to make the local news, the federal government passed an infrastructure bill that devotes a very significant amount of money to repairing our old and decrepit drinking water infrastructure. This got me to thinking what the world would be like (my local universe anyway) if the regulators were allowed to dream big. Here is the fantasy that I came up with: Instead of forcing municipalities to build new treatment plants that will cost a fortune and not solve the problem, let’s get those same municipalities to invest in infrastructure to use the treated water on land.

Right now, we get most of our water from rainfall and snowmelt. We do have some excellent water in Seattle, up to New York City standards according to my taste buds. Much of the infrastructure was established back when adequate snow levels weren’t a concern. These days 3,000 feet is a very iffy elevation. Five thousand feet is even not always guaranteed. Whereas in some states use of reclaimed water has made significant headway, here in the Pacific Northwest decisions on use of reclaimed water are made in November when it seems as if the rain will never stop and the sun will never shine. Perhaps it is time to change that. If funds were used to start rebuilding our potable water infrastructure to go from the treatment plants back to lawns, gardens, golf courses and even taps, we would have a sustainable and climate resilient source of water.

In addition, a significant portion of the snow melt or sleet melt (depending on elevation) could then go right into Puget Sound. It would also increase stream flow during the dry summer months at levels sufficient to make an impact. Finally, it would do as much to help dilute the excess nitrogen in the Puget Sound as building a new treatment plant. In other words, instead of spending money to get you quite probably no detectable result in terms of reducing nitrogen levels in the Pacific Ocean and still leave you facing an enormous problem, you could use that money and actually get measurable results on multiple fronts.

Quick Estimate Of Impact

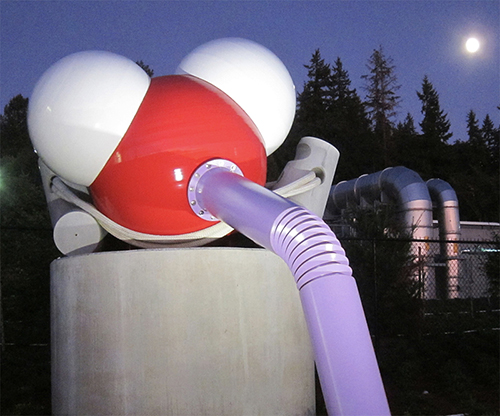

Sculpture of a water molecule by Buster Simpson at the Brightwater Wastewater Treatment Plant in King County, which was built with capacity to supply reclaimed water, as represented by the lavender pipe.

The two biggest wastewater treatment plants in King County treat between 200 and 600 million gallons per day. All of that treated water goes into Puget Sound. It is a literal drop in the bucket. Puget Sound contains over 26 cubic miles of water. Our drinking water comes from two primary sources: the Cedar and Tolt River watersheds. Combined they supply water for 1.4 million people. Average per capita water use in Seattle is low, about 50 gallons/day. The 1.4 million people using 50 gallons/person totals 70 million gallons. That means the reclaimed water would be more than enough to supply demand in the region.

The costs for this type of project would likely far exceed the costs for building treatment plants but you would get something for your money. This type of project would be an excellent use of funds from the Federal infrastructure bill, one that helps build resilience in the face of climate change impacts.

This is one example of what a water future could look like. We are now going to have an incredible opportunity to make that future happen. The best and most forward thinking solutions will vary by region. But in each case solutions should be sought that tackle more than one problem. Sustainable sources of water, optimal use of existing water resources, increasing resilience to climate change, and ecological enhancements with water are the four that come to mind. Solutions are best if they can achieve multiple end goals. Who doesn’t want to save the orcas and shower too?

Sally Brown, BioCycle Senior Adviser, is a Research Professor in the College of the Environment at the University of Washington.