Technical Advisor on odor from England’s Environment Agency discusses odor pollution control options for organics recycling facilities in the context of business planning, management and abatement.

Nick Sauer

BioCycle November 2014

Many cases of severe odor pollution are indirectly caused by too much material on the site. This results in difficulty moving material, piles that are too large to aerate and extended treatment times.

Cost-Effective odor pollution control at organics recycling facilities involves three general approaches — planning, management and abatement. Planning considers those aspects of the business plan that might sometimes be thought of as fixed. These are factors such as who the customers are, what services are provided and the premises where business is conducted. These factors frequently offer the greatest potential for odor control, but can involve difficult discussions with customers or staff, require investments and present risky decisions if not included at the planning stage.

Effective management is essential to both the business and the process. For example, excess waste inventories make effective site management much more difficult and dramatically increase the potential for odorous releases. Holding more material than necessary can be an indication that a site is poorly managed or in trouble financially.

Containment and abatement can be the most expensive, least effective and most technically demanding aspect of odor management. The key is to build upon the first two approaches (planning and management), have realistic expectations, recognize the technical challenges and keep containment and abatement as small and simple as possible.

The Environment Agency (EA), England’s environmental authority, is responsible for regulation of environmental impacts from permitted (licensed) organics recycling facilities. In England, the selection of specific odor pollution control methods is the responsibility of individual operators. However, the EA requires appropriate methods to be used in accordance with legal requirements to minimize pollution impacts. This article is intended to stimulate discussion about how best to achieve this.

The discussion and recommendations pertain directly to composting operations. However, the principles and practices can be utilized for any facility processing organic wastes, including anaerobic digesters.

The Business Plan

For purposes of this article, a business plan includes the service (or product) and the context in which that service is provided. A number of business plan factors influence the relative risk of odor pollution from waste materials.

Material Freshness

The first is the odor potential of materials as received. Materials of concern may be inherently odorous (spicy food ingredients), have an inherent potential to become odorous (putrescible materials) or may have already become odorous (putrid materials). The somewhat imprecise concept of material freshness is central to managing most putrescible waste. The rate of odorous breakdown of putrescible materials will depend upon a wide range of factors such as the inherent tendency of waste materials to putrefy, moisture levels, age, storage temperature and mixing.

Control of these important factors can be lost in a number of ways:

• Contracts may not specify waste freshness factors.

• Operators may find it difficult to communicate or enforce freshness factors with one-time or infrequent customers.

• Waste may be preprocessed at a transfer station or materials recycling facility (MRF) where it spends an indeterminate period of time under poor storage conditions.

• Operators may rely on identifying highly odorous waste as it arrives.

• Business may be disrupted by industrial action, holiday collection schedules, adverse weather or a multitude of other incidents.

• Business may face financial difficulties that make strict inventory controls or turning away of unsuitable materials difficult.

Distance To Odor Receptors

The second business plan factor is distance to sensitive receptors (people). Setback distance is a major factor in odor pollution. Limited research conducted by the EA suggests that it is unusual for ground or low height emissions to result in complaints from people more than about 1.2 miles (2 km) away, although with notable exceptions. Impacts from sites with significantly elevated stacks and very high emissions have been observed up to about 4 miles (7 km) away, but this is unusual. While recognizing that complaints are only one indicator, it is evident that odor pollution is mostly a local problem.

Ground level emissions (including low stacks) are conveyed beyond the site boundary under turbulent conditions. Turbulence partly results from wind speeds at a moderate elevation (~ 65-feet or ~20m) being higher than ground level wind speeds. In turn, this causes highly variable odor exposure to individuals within a few hundred meters (e.g., 1,000 feet) downwind, even when emissions are constant. Because of the way the human nose functions, variable odor concentrations are more noticeable, are perceived as more intense and can cause greater distress.

In parts of the world (some Australian states and Canadian provinces), setback distance standards are used to mitigate odor and other pollution impacts. Relatively high population densities and historical development patterns in England make this approach less practical. Nevertheless, decision makers need to be mindful that the challenges of preventing local amenity pollution impacts through dust, noise or odor will be much greater when sensitive receptors are close.

Sensitivity Of Receptors

The third business plan factor is the sensitivity of people to odor and any resulting annoyance. The context of an individual’s exposure to odor can have a dramatic effect on their reactions. People who are distracted by work or other demanding activities tend to notice odors less and be less vulnerable to annoyance, while the same people who are resting or eating may be much more sensitive.

Some literature references suggest that individuals who are “dissatisfied with their level of health” may be more sensitive to odor annoyance. Our experience has highlighted a number of cases where people who perceived odor became very upset when they felt that there was a threat to the health of someone close to them. Examples include parents of children with asthma, husbands of pregnant women or spouses of people with a terminal illness. There are also literature reports that women in their first trimester of pregnancy often perceive odors as more intense and may experience increased levels of nausea, while their ability to detect odors at low levels remains unchanged.

Perceived odors must normally be interpreted before they have any meaning. Some of these, such as a putrid smell means not safe to eat, may be generally agreed upon. Other meanings may be apparent from their circumstances. For example, people who have an economic interest in the odorous activity are reported to experience a lower overall level of annoyance than those who do not.

In summary, the business plan aspects discussed here relate to what facilities plan to do and where they plan to do it. Like all foundations, these tend to be easier to move and adjust in the planning stage and more difficult to change once contracts have been signed, investments have been made and construction completed. Failure to adequately consider these issues at an early stage may cause pollution, require expensive remedial action or, in extreme cases, cause the business to fail. Consideration of these issues is still recommended for sites that are already established.

Management And Process Controls

Process control is about reducing the odor potential of materials held on site. If feedstock materials are fresh, then they should be managed so that they do not become foul smelling. If they arrive foul smelling, then they should be managed so that their odor potential is reduced as rapidly as possible. Peripheral processes such as leachate holding lagoons also need to be managed to keep their odor potential as low as possible. Overall quantities of odorous materials should be maintained at the lowest possible level. Best practice controls may differ significantly from one process to another, and it is important to consider the needs of each process individually. However, a number of general principles are helpful.

Inventory Controls

First–in, first–out (FIFO) management of putrescible feedstock waste is difficult to achieve. Waste stored in bays must normally be added to from the front and removed from the front, as this is the only available point of access. Pits that are accessed only by overhead claws pose particular difficulties in this regard. Storage in bays, open halls or pits therefore tends to result in a last–in, first–out (LIFO) inventory control system where old material may sit festering at the back of the hall (or bottom of the pit) for a considerable period.

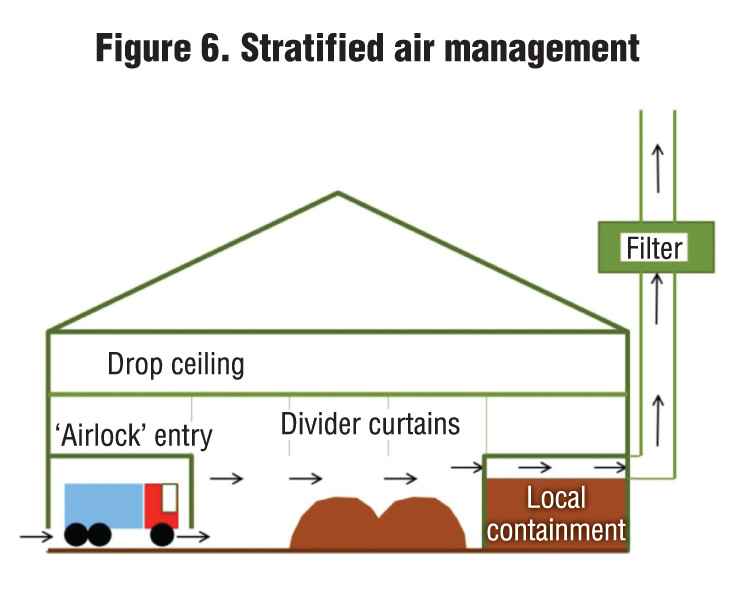

An alternate bay system may provide a useful compromise between the short holding times of FIFO and the convenience of LIFO. In this system (Figure 1), at least two bays are required and each bay must be completely emptied before additional waste can be tipped there. For small sites that cannot accommodate two bays, an all-in, all-out system may be more suitable. Under this system, the reception area must be periodically cleared — usually at the end of each working day.

Critical Control Points

Managing any process first requires a clear understanding of how it works. What factors limit the process and cause loss of control and productivity? Many cases of severe odor pollution observed by the EA are indirectly caused by too much material. This results in difficulty in moving material, piles that are too large to aerate and extended treatment times. Clearly understanding and monitoring against real site operational capacities (as opposed to permit limits) is a nearly universal critical control point.

Many process control points for composting will relate to looking after the microbes. Too hot, too little oxygen, too much moisture or the wrong chemical conditions can result in a build-up of odorous chemicals. Get it right, and not only will odors be reduced, but the stabilization process will move along more quickly as well, leaving a higher quality finished product in a shorter time.

Critical control points may also need to be applied to materials that are peripheral to the process. Leachate with a high biological oxygen demand (BOD) can quickly become anaerobic and highly odorous without a constant supply of air or other source of oxygen. Management of leachate before it becomes odorous is generally quite straightforward. However, odor impacts can be very high if leachate is not effectively managed.

Containment And Abatement

Caution should be exercised when it comes to using buildings, ducts, fans and filters to control odorous emissions. The EA frequently encounters systems that are expensive to buy, maintain and operate, with little or no benefit. Sometimes this is due to a single component that is inadequate or has failed. More often, systems don’t work because they were ill conceived, poorly designed and not installed properly. Ad hoc additions, modifications or maintenance can also disable an otherwise effective containment and abatement system.

Well-designed and implemented systems can play a useful role in odor control. However, it would be silly to receive high risk (from an odor generation standpoint) feedstock materials into a large site that has poor process controls and is very close to sensitive receptors. Even a well-designed containment and abatement system would be very unlikely to prevent unacceptable odor pollution in this context.

So, once a facility has …

• Renegotiated its contracts to ensure fresh feedstock waste;

• Considered alternative sites further from sensitive neighbors;

• Minimized the quantities and holding times of materials held on site;

• Brought the process fully under control; and

• Is managing the site with effective monitoring and use of critical control points …

then it will want the best possible value for money from the odor containment and abatement system.

“Big Barn” Approach

The most common approach seen in England involves a single large building that may or may not have been designed as a containment feature. This building will be fitted with a large exhaust fan ducted to an abatement system that is sized to provide a certain number of air changes per hour. While this approach may appear simple, it has a number of critical faults:

• The movement and effective treatment of large volumes of air is expensive and requires a lot of power.

• It may result in poor quality indoor air or even dangerous conditions for workers due to poor visibility or heat stress.

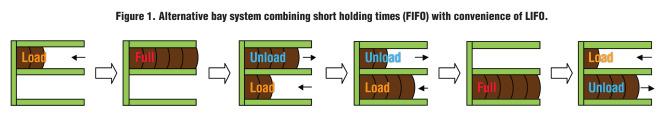

• Short circuiting of air flow is common and it is difficult to ensure that all parts of the building are ventilated to an appropriate standard (Figure 2).

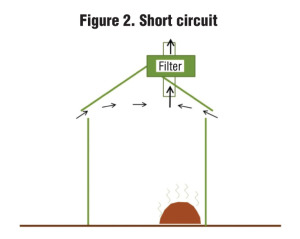

• The fabric of the building must be maintained to a very high standard and air extraction rates must be high to prevent infiltration of transient flows from differential air pressures caused by even moderate wind speeds (Figure 3).

• Unless fitted with an air lock entry, containment will be completely compromised every time a door is opened to admit vehicles.

In short, rather than using the building as primary containment, a much better strategy is to take steps to improve indoor air quality. That way, fugitive emissions through the fabric of the building or when doors are opened will have a minimal impact and working conditions will be greatly improved.

Localized Containment

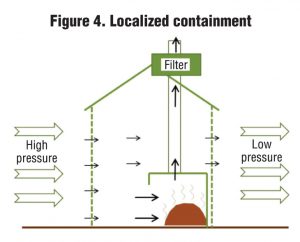

Even most leaky buildings are very capable of creating low indoor wind speeds in the face of outside weather. This creates the opportunity to use loose fitting containment measures around localized odor release features or activities, such as shredders or screens (Figure 4).

This approach has a number of important advantages:

• Air flow rates required for effective ventilation and dynamic containment are much lower due to the small size of localized containment features and low wind speeds within the building.

• By containing the most serious odor emissions sources within localized containment features, air quality within the building is improved.

• Any air extraction from within localized containment features must be drawn from inside the building, so the same air also serves to ventilate the building as a whole, at no additional expense.

• Efficient use of air means that a better standard of containment can be achieved through the extraction and treatment of lower volumes of air. This will reduce costs, and improve abatement performance for most systems.

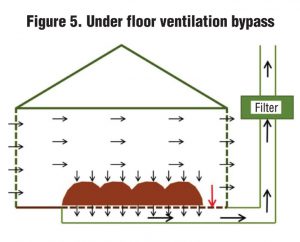

Downdraft Containment

A variation on the local containment approach is achieved by drawing air down through waste by suction into an under floor plenum (Figure 5):

• This requires careful design by competent air flow engineers and regular monitoring to ensure that air is flowing where it is needed.

• Some evaporation will still take place on the surface and it is unlikely to have much effect when material is disturbed.

• The approach works best for materials that are not too deep, relatively homogeneous, evenly distributed and with adequate porosity. This may make it suitable for aerobic composting, but less so for storage of freshly delivered waste.

Airlock Entry Systems

If the air quality within a building has a low odor potential, then opening doors will not result in significant releases and an airlock entry is probably not needed. However, where indoor air is highly odorous and a building is relied upon for containment, vehicle entry doors can be a major source of regular short-term releases. Due to the nature of odor perception, regular short-term exposure to local residents will cause a disproportionate annoyance response.

Double door airlock entry systems should allow the entry and exit of vehicles while preventing convective release of odorous air from the main building. They must also be adequately purged of odorous air before the outer door is opened. Claims that negative building pressure can be maintained with vehicle access doors opened, or that devices such as air curtains or misting systems can maintain containment, are simply not credible.

Questions that need to be asked when considering installation of double door vehicle airlock entry systems include:

• Do they allow the efficient entry and exit of vehicles?

• Will convective release (purging) of odorous air from the main building be prevented?

• Will there be any disruption to the efficient operation of other odor containment measures?

• Does the system ensure that air quality within the airlock is of sufficient quality, so that there is no significant release of odor when the outer door is opened?

The answers need to be carefully considered when designing the system and establishing operating procedures.

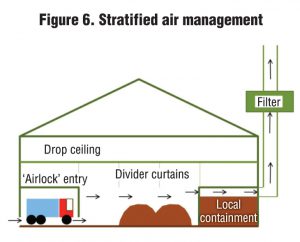

Stratified Containment Systems

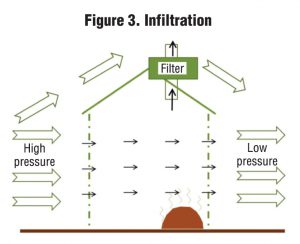

Purged airlock entry systems and localized containment features are examples of hard barrier controls. These can be used individually, or in combination, to provide a multilayered or “nested” containment system (Figure 6).

Soft barriers can also play a useful role in containment of contaminated air. For example, air can be channeled through buildings in such a way as to introduce it at one end and extract it at another. These pathways do not need to be straight. Air can be made to meander around flimsy barriers in a serpentine motion or constrained by lowered ceilings. All of these measures can be made to constrict the air path and therefore increase the average velocity through the desired pathway. Higher velocities in the direction that facility operators want air to move mean less opportunity for unintended air currents in the opposite direction.

The natural movement of air can sometimes also be exploited. Hot air is lighter than cold air and humid air is lighter than dry air. Odorous hot humid air from composting will therefore rise. This stratification can be encouraged by insulating the roof to prevent high level cooling and condensation, extracting odorous air to abatement from the highest point and providing cool, dry fresh air at ground level. This stratification may be disrupted by uncontrolled drafts caused by open doors, poor building containment or other activities within the building.

Treating Highly Odorous Air

If containment systems are designed properly, there is a potential to produce smaller quantities of highly odorous air. These might be from an enclosed screen, down draft containment systems or a tank filled with foul smelling leachate. The most common approach is to commingle this highly odorous air with large volumes of less odorous air before treatment in a high volume abatement system.

Commingling air from very different sources in this way creates several problems and excludes a number of possible opportunities. Potential problems caused by commingling include:

• Inconsistent mixing may vary the load on abatement systems from one second to the next, causing poor performance.

• The abatement efficiency of a high volume system may only be 90 percent or lower.

• Concentrated sources may cause toxicity problems with systems such as biofilters.

• One of the odorous streams may have components with different chemical characteristics, such as organic acids (butyric acid), ammonia, or low water solubility (carbon disulphide), which are unsuitable for a particular high volume air treatment method.

Opportunities missed include:

• By keeping highly odorous sources separate, at least initially, very effective low volume abatement methods, such as thermal catalytic oxidation, may become affordable.

• As long as air quality is satisfactory, equipment such as boilers or generators could be used for abatement of small air volumes. This approach typically features very high abatement efficiencies.

• Simple and inexpensive low volume single pass water scrubbers can be used to cool (and therefore dry) air, resulting in condensation and scrubbing of some odorous chemicals. This approach has been successfully used to pretreat highly odorous air before final treatment. The volumes of cool and clean(ish) water consumed, and used water disposed of, correspond to the volume of air treated.

• Specialized pretreatments, such as acid scrubbing to remove ammonia or peroxide scrubbing, may be used for removal of specific odorous chemicals or to precondition air before the main treatment stage.

Use Proven Odor Abatement Methods

When considering odor abatement options, there are some basic questions to consider: Is it understood how the technology works? Are the sources of information promotional literature from the vendor or peer reviewed journals and textbooks? Not understanding how a system works leaves facility managers poorly equipped to use it effectively or recognize circumstances that could cause it to fail.

All odor control systems have their own advantages and limitations. Understand what those are and review whether employees will be able to consistently manage the site with these in mind. For example, untreated activated carbon works well for a wide range of odorous hydrocarbons and can be heavily loaded. However, it has limited capacity, gives no indication when that capacity has been used up and is inhibited by hot or wet conditions. With an application such as abating emissions from a tank vent, then it may be occasionally heavily loaded for short periods of time as the tank is filled and air is displaced. If the temperature is moderate, then absolute humidity will also be low and this technology might be a good fit. However, if the operator tries to use the same equipment to abate a stream of hot wet odorous air from composting emissions, then it may stop working within hours.

Proven technologies will have well documented operational, maintenance and monitoring associated with them. How much does this cost and what can be done to keep costs under control? One operator trialled a biofilter, but then discovered that the system benefited from regular maintenance. The facility couldn’t perform this maintenance easily because the system was not designed for easy access. The second system was based on ground-level bays. By removing the end gate, a front-end loader could be used to quickly remove the entire bed of filter media. The media could be washed and screened, additional material added and reloaded into the bay. By the end of the day the biofilter could be rejuvenated and back in operation with minimum cost and disruption.

End of pipe odor abatement systems can usually be monitored by dilution olfactometry on its own, or in combination with surrogate methods. Of course overall system performance will depend upon consistently effective containment as well, which is much more difficult to assess directly. Containment system performance is best monitored by identifying whether individual components are behaving as designed and creating the designed conditions. Parameters such as air flow in ducts and pressure differences are much more reliable than fan power consumption, which could indicate a variety of conditions.

Indoor ambient air treatment methods such as misting, ozone or ionized air treatments are much more difficult to monitor and there is little or no evidence of benefit for many systems on the market. If an indoor abatement system were to show promise under controlled conditions, it would be necessary to demonstrate that those conditions were representative of the indoor environment being treated.

Water misting systems with deodorizers are often used at the boundary of odorous sites. However, at present, the author is not aware of any credible methods to monitor the effectiveness of outdoor ambient air treatment methods. There is also no theoretical reason to expect any significant odor removal benefit from these systems. Chemical reactions depend upon intimate mixing, which is impossible to control in outdoor air.

It is understandable that vendors of odor abatement systems will want to present their systems in the best light. However, as a consumer, facilities need to carefully consider how much of what is being said is unfounded optimism or hyperbole, and how much is based on scientific evidence. If it sounds too good to be true, then it probably is.

Seek Professional Advice

Advice from qualified and experienced professionals will cost money. However, not getting good quality advice can cost much more. Designing large or complex air handling systems requires a thorough knowledge of air flow engineering. Review the engineer’s qualifications (e.g., HVAC), membership of professional associations (are they vetted or do they just pay dues) and previous projects. The odor abatement and containment project should include sufficient ongoing monitoring to indicate whether the system is moving air from each location that operators want to extract from, to each location they want to deliver it to, and at the right rate of flow.

Inquire whether the professional’s work is backed by a guarantee or performance bond. What specific circumstances or performance measures would allow the operator to make a claim?

Also inquire whether the engineer is independent of the equipment suppliers. If not, consider retaining an independent engineer to review the work and help negotiate warrantee provisions. There can be significant advantages from combined engineering supply and build, particularly if suppliers are commissioned to undertake ongoing maintenance or even day to day management. In these situations, warranties become much more straightforward as long as the system is not subjected to conditions that are outside of the stated operating parameters. Clear operating conditions and performance measures will be critical in any event.

It is not unheard of for an operator to commission a consultant to design a containment and abatement system, and then decide themselves to make modifications or simply not implement the system in the way recommended. No engineer or manufacturer will warrantee their work if the facility changes the design itself or fails to operate equipment within stated design parameters. Any modifications need to be subject to the same level of engineering input as the original design.

Wrap Up

Before investing in a containment and abatement system, it is always wise to evaluate another approach that may be low cost or even free. It can be well worth a facility operator’s time to review and audit the process:

• Reconsider the business plan. If a facility is in the planning stage, it may be able to make major changes with minimal effort. If a facility is already established, it may help to speak candidly with customers about reducing the odor potential of feedstock materials and therefore reduce management costs.

• Audit management of odorous materials on site. Consider whether the quantities being held can be reduced or whether, by altering conditions, the odor potential of the materials can be dramatically reduced. Start with issues that are relatively easy and inexpensive to resolve, such as leachate management.

• Have containment and abatement measures reviewed by a competent engineer and ask them to maximize containment and improve working conditions while minimizing volumes of air moved. Several different specialists may be needed for this.

Nick Sauer is a Technical Advisor on odor with the Environment Agency in England (nick.sauer@environment-agency.gov.uk).