Vern-Mont Farm installed solids separation equipment and a rotary compost drum to produce bedding for its milking cows.

Robert Spencer

BioCycle September 2016

Pipe in foreground conveys water squeezed out of manure back to storage pit with less manure solids and associated phosphorous and other nutrients. Photo by Robert Spencer

But as the wood pellet market has grown, so has competition for sawdust, and the cost. In New England, sawdust comes in a variety of forms, from green to kiln dried, and soft or hardwood, with prices about $12 to $15/cubic yard (cy), delivered to the farm. Many sawmills have also closed, further driving up the price, particularly due to longer trucking distances.

Screened sand in New England is valued as bedding because it is inorganic and does not provide favorable conditions to host bacteria. However, sand can cost as much as sawdust, its quality varies depending on the source, and it’s heavy to transport. A major disadvantage of sand as bedding is it is very abrasive to manure handling equipment, particularly drag chains and pumps.

For a medium size dairy farm in New England milking 500 cows per day, bedding can cost $50,000 to $100,000/year, or more. Often, supplies become limited in winter months when demand for wood chips is high.

Dairy Manure Solids Bedding

A wide range of practices are used on large and small dairy farms to produce bedding made from dairy manure solids (DMS). The least cost systems pump liquid manure to a screw press, or other type of press, that mechanically squeezes water from the manure. This produces a “green bedding” that is used without any heat treatment process. Many dairy farms utilizing anaerobic digesters (AD) to generate energy from manure also separate the solids from the digestate, typically with a screw press, and then use the digested manure solids as bedding. Most manure AD systems operate in the mesophillic temperature range (about 100°F), and therefore don’t subject the manure to a thermophillic (131°F) process to further reduce pathogens (PFRP). However, studies indicate substantial reductions in pathogenic organisms at mesophillic temperatures.

Farms that want the extra assurance that the DMS have been subjected to higher temperatures utilize composting technologies, primarily aerobic rotary drums. In North America, a number of companies market systems to separate solids from liquid manure, and then compost it at temperatures of over 131°F for 18 to 24 hours, prior to using it as bedding. Although it may not meet the time and temperature requirements of PFRP, which is not required for manure composting as compared to biosolids, temperatures over 131°F are presumed to reduce concentrations of pathogenic organisms.

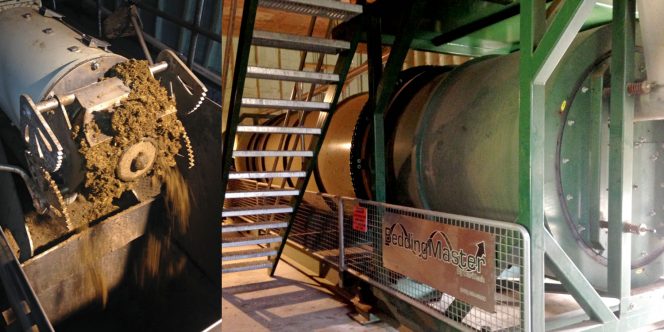

Solids from the separator (left) are loaded into Daritech Bedding Master rotary drum (right), which consistently operates at 140°F to 160°F. The separator is mounted above the drum. Photo by Robert Spencer

Vern-Mont Farm Dairy

Vern-Mont Farm, LLC is a fifth generation dairy farm in Vernon, Vermont, milking about 575 cows, with another 400 young stock. Approximately 5 million gallons of liquid manure are generated annually, and stored in an 800,000-gallon concrete tank, and a 2-million gallon fiberglass tank. The manure is spread on approximately 700 acres of crop fields in the fall, and again in the spring prior to planting.

After years of using both green and kiln dried sawdust from a local sawmill as bedding, Vern-Mont Farm started evaluating use of DMS as bedding. In March 2009, a dewatering demonstration was conducted with a PT&M Model E 10-inch screw press. Approximately 3 cubic yards (cy) of pressed manure was loaded in a mobile 4-foot diameter by 8-foot long BW Organics rotary drum, and composted for 48 hours. For comparison, 30 cy of pressed manure was put in a concrete bunker and composted by turning the pile every few days for a month. Material from both the drum and the turned pile were used as bedding in a limited area of one barn, and were determined to be comparable to green sawdust in terms of moisture content and particle size.

Intrigued by the prospect of considerable financial savings — and having a guaranteed consistent source of bedding by using the solids — owners Alfred Dunklee, and his son, Jeff, visited a number of farms with different DMS systems in operation. They ultimately solicited proposals from a number of vendors for both aerated static pile (ASP) composting, and rotary drum composting. Due to significantly smaller space requirements for a rotary drum as compared to ASP composting, they decided to proceed with a rotary drum. The DariTech Bedding Master system was selected. In Spring 2015, new pumps, piping, valves, reception/mixing pit, EYS tapered screw press, and the rotary drum were installed. New buildings were constructed for the reception pit, as well as the press and drum, for a total investment of approximately $400,000.

Manure from the cows being milked is scraped out of three barns with a skid-steer, or a mechanical scraper, into three pits from where it is pumped through underground pipes into a new reception pit where an agitator keeps it mixed — an important factor for getting consistent solids content into the press, and a consistent bedding product out of the drum. Wash water from the milking parlor is also pumped through one of the barn’s manure pits. Valves were installed to allow for liquid manure to bypass the new reception pit to the large concrete storage pit during planned or unplanned maintenance of the dewatering and composting equipment.

Together, the screw press and rotary drum produce bedding that has a moisture content of about 55 percent, with a bulk density of 250 lbs/cy. Dewatered manure remains in the rotary drum for approximately 24 hours. The composted DMS is used as soon as it is produced, providing fresh bedding to the cows three times per week.

“Maintenance expenses for the drum, pumps and screen have been greater than projected, but are still saving us significant amounts of money,” notes Jeff Dunklee. He adds that with just over one year of operation of the separator and the rotary drum, “our results have been consistent with the experiences of other operations we looked at, maintaining milk quality and udder health while reducing the expense of bedding.” After spreading manure this fall, the Dunklees will have better information available on the cost savings of manure spreading since less hours may be required to apply the manure due to reduced solids content, and more gallons per acre.

Vern-Mont Farm received a $50,000 grant for the project from the Vermont Agency of Agriculture, Food & Markets (VAAFM) under the Best Management Practices and Alternative Manure Management Programs. It qualified for the grant based on the following factors:

• Limited manure storage, and by separating out manure solids, avoid construction of additional manure storage capacity.

• Limited land base restricts number of cows that can be raised, i.e. too much manure for acres of land available for spreading manure.

Another factor considered by VAAFM when providing this grant to farms for such manure management technologies is a seasonal restriction on manure spreading from December 15 to April 1. However, once the manure is composted, a farm can request an exemption from the seasonal restriction in order to spread compost in the winter months.

AgriLab Technologies’ Drum Dragon is connected to the rotary drum. It captures heat in the drum’s exhaust, which is used to make hot water for dairy operations. Photo by Robert Spencer

Heat Recovery

The Vern-Mont Farm rotary drum is inside a building; year round, it consistently operates at 140° to 160°F, with exhaust gas vented outside of the building. Since the farm does not have nearby residential neighbors, it wasn’t necessary to treat the exhaust gas in a biofilter. “After the rotary drum system had been operating for a few months, I kept looking at all that hot exhaust steam coming out of the drum, thinking there must be something we can do with that heat,” recalls Jeff Dunklee. “Like most dairy farms, we use a considerable amount of hot water each day to clean the milking parlor, and wash employee’s uniforms and the cloth rags used to clean cow udders. Then we learned about Agrilab Technologies Inc., which is also a Vermont company.”

Agrilab Technologies recently developed the Drum Dragon 200™ system, which captures the heat in the exhaust of a rotary drum composting system. The heat can be used to make hot water, as well as for space heating and drying compost. Agrilab Technologies has over six years of operating experience recovering heat from aerated static pile composting systems (see “Advances in Compost Heat Recovery,” March/April 2015). The installation at Vern-Mont Farm is the company’s first application on a rotary drum.

“Since the Drum Dragon started operating in June of this year, we have been receiving water at the milking parlor at average temperatures of 134°F, about 30,000 Btu per hour, which is projected to save us about $5,000/year, with propane at $1.50 per gallon,” adds Dunklee. Agrilab Technologies installed 400 feet of insulated pipe that conveys water to and from the Drum Dragon to the milking parlor. The pipe is installed about 15 feet underground to minimize heat loss compared to using overhead pipes inside the barns. Agrilab Technologies estimates that if propane costs increase to $2.00 or $3.00/gallon, annualized savings could be $6,288 to $9,432/year, respectively.

Vern-Mont Farm is evaluating the sale of carbon credits that result from diverting manure to aerobic composting rather than emitting methane generated by anaerobic conditions in the liquid storage tanks on the farm. Carbon credits may also be available from the reduction in propane use due to heat recovery from the composting drum.

Robert Spencer, an environmental planning consultant in Vernon, Vermont, is a Contributing Editor to BioCycle.