A 2014 study sought to answer the question: Can diversion and composting be done cost-effectively, with minimal fiscal impact on Rolla, Missouri’s businesses and residents?

Craig Coker

BioCycle March/April 2015

The City of Rolla, Missouri is located in the Ozark Highlands region of the central U.S., approximately 100 miles west of St. Louis. Rolla has a population of almost 20,000 and is home to the Missouri University of Science and Technology (MS&T), with its 9,000 students. Historic U.S. Route 66 runs through the middle of Rolla. Settled in the mid-19th century, it is a classic American small town.

The City’s Environmental Services Department (ESD) collects 20,000 tons of solid waste from residential and commercial accounts annually, taking the MSW to a transfer station. Collection is done in 20 cubic yard (cy) rear-packer trucks. The City also offers curbside recycling collection, which is taken to a city-owned and operated recycling center. Recyclables are collected with a curbside sorting trailer pulled by a rear-packer (Figure 1). Between collected and dropped-off recyclables, 5,400 tons were recycled in 2013, of which 2,600 were yard trimmings. Yard trimmings are currently ground into mulch and given away.

“In 2013, we realized that we were not going to be able to improve our recycling rate without capturing organics,” explains Brady Wilson, Rolla’s Director of Environmental Services. “We wanted to see if we could understand the cost implications of a voluntary diversion program for our commercial customers and what interest there might be in a food scraps diversion program.” The author was retained by the City in 2014 to conduct a food scraps diversion feasibility study.

Key Questions

Three key questions addressed in the study were:

1) How much capturable food waste is generated, where is it generated, and how could it be collected?

2) Where could a composting facility be located to handle food scraps and yard trimmings?

3) Can diversion and composting be done cost-effectively, with minimal fiscal impact on Rolla’s businesses and residents?

This article examines the issues associated with the third question.

A review of the City’s solid waste and recyclable tonnages led to the conclusion that, by Year 2020, somewhere between 2,300 and 2,500 tons of source separated organics (SSO) could be potentially captured in a voluntary diversion program. The major commercial and institutional sources of food scraps were MS&T (200 tons/year), the Rolla Public School system (75 tons/year), the Phelps County Medical Center (25 tons/year), college-town restaurants (700 tons/year) and fast-food eateries (450 tons/year). Residential sources of food scraps were estimated at 200 to 500 tons/year, depending on the participation rate in the program. “As we interviewed potential program participants, we found highly variable levels of understanding and interest in what we were contemplating,” Wilson notes. “The University was highly interested, but some of the people we interviewed were not. One common theme we kept hearing was ‘This won’t cost me any more money, will it?’”

The Rolla ESD’s 20 cy rear-packer trash trucks are equipped with cart lifters. The City indicated a preference for using that same truck for a SSO diversion program to take advantage of the parts inventory and skilled mechanics in the ESD who are already familiar with its rear packers. Commercial collection containers would be either 90-gallon rollcarts or 1-2 cy dumpsters (depending on quantities); residential collection containers would be 35-gallon rollcarts. One challenge in establishing a separate collection infrastructure with commercial customers is that the majority of establishments in Rolla have separate, walled enclosures for solid waste management and additional room for more collection containers is minimal (Figure 2).

The City’s commercial solid waste management fees are based on a monthly service charge, with the fee varying depending on size of collection container and frequency of pickup. Charges vary from $40.30/month for a one cy dumpster collected once per week to $774.05/month for a 6 cy dumpster pulled 5 times per week. Service charges are based on estimates of collection labor time and costs, amortized equipment costs, fuel and maintenance costs, transfer station tip fee and administrative costs. Residential service is also charged on a monthly basis, with weekly collection service. Fees vary from $11.50/month for a 35-gallon rollcart to $14.00/month for a 90-gallon rollcart. Service charges for residential service are calculated similarly to commercial service.

Economic Analysis

The economic analysis used in this study included estimates of capital and operating costs for a new food scraps collection service, estimates of capital and operating costs for the development of a new composting facility (methods evaluated included open-air turned windrows and aerated static piles in bunkers) at one of two candidate sites, estimates of potential revenues from avoided transfer station tip fees and compost product sales, and development of a new proposed Food Scraps Diversion Service Charge rate sheet for commercial and residential program participants.

Capital Costs

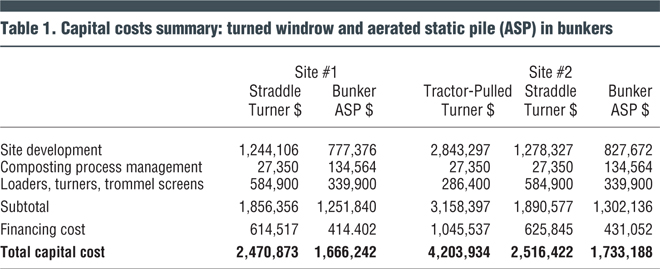

Composting capital costs were estimated for site development, composting process management, and mobile equipment at a facility planning level of accuracy (i.e., +50%/-30%, or as much as 50% more or 30% less than the estimate). Site development cost components included clearing/grading, stone subbase, asphalt pads for all process areas, security fencing and gating, power/lighting, water, sewer, storm water pond and storm water recycle system. Composting process management costs included windrow covers and hold-downs (for the turned windrow alternatives), bunker silo walls, floors, aeration blowers and timers, and aeration piping (for the aerated static pile alternatives), process control software, monitoring instruments, uniforms/work shoes, office furniture, and computers. Mobile equipment included a tractor and a pull-behind windrow turner or a self-propelled straddle turner (for the turned windrow alternatives), mechanical mixing equipment (for the aerated static pile alternatives), front-end loaders, and a trommel screen. For all alternatives, the capital costs were assumed to be financed with a debt instrument at 3 percent interest rate for a 20-year term. Capital costs for the composting alternatives are summarized in Table 1.

The higher capital costs for the tractor-pulled turner alternative reflect the larger land area needed (and, thus, area paved). Similarly, the smaller processing footprint of the aerated static pile alternatives is reflected in the lower capital costs. The difference in costs between the two sites were: clearing costs on Site #2 not needed on Site #1, longer distance to bring in electricity on Site # 2, allowance for well and septic system at Site 2 versus tying in to existing utilities in a street adjacent to Site 1.

Operating Costs

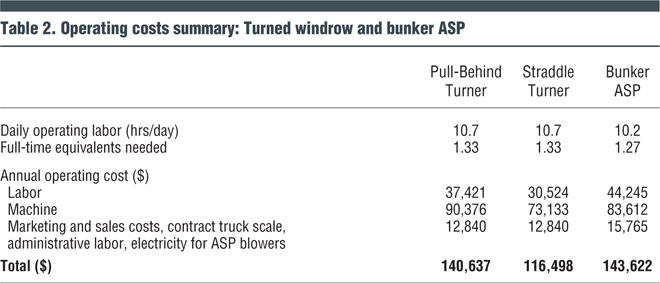

Operating costs for composting were estimated for administrative costs, labor costs, and machine costs. Administrative costs included a rented office trailer, electricity, using contract scales for weighing trucks, and for site administration and product marketing and sales. Labor costs were based on a labor rate of $20/hour and the facility being open 5 days per week, 52 weeks per year. Machine costs were based on a repair and fuel usage rate of $50/hour. Time-and-motion estimates were prepared for each step in the compost manufacturing process in order to estimate the number of full-time staff needed for the facility. Operating costs for the alternatives are summarized in Table 2.

The higher estimated operating costs for the Bunker ASP option are due to the assumption that curing piles would be turned with a bucket loader, which is relatively slow and inefficient, but is still less than using a windrow turner for a very limited application.

Revenues—Compost Sales

And Avoided Tip Fees

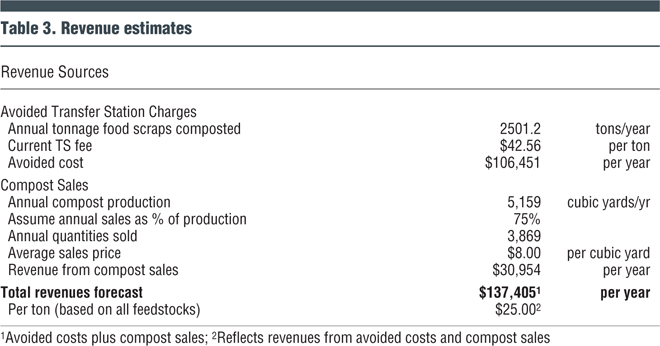

Revenues were estimated for compost sales assuming 75 percent of annual production went to market (the other 25% would be used in-house on city projects) and that the average sales price would be about $8.00/cy. That is a low price relative to what composters in St. Louis and Kansas City are selling product for, but it is more in line with traditional municipal compost pricing. Insofar as a composting facility would divert food scraps and SSO away from the Transfer Station, there is an avoided cost that could be considered a form of revenue. Both of these revenue sources are considered “potential” revenues. While there has been good demand for the City’s mulched yard trimmings, compost is a different product, and a well thought out compost marketing and sales plan would be needed. Also, as this SSO diversion program is intended to be voluntary, there are no assurances that the levels of diversion will reach the amounts forecasted in this analysis. Revenue estimates are presented in Table 3.

Per Ton Estimates

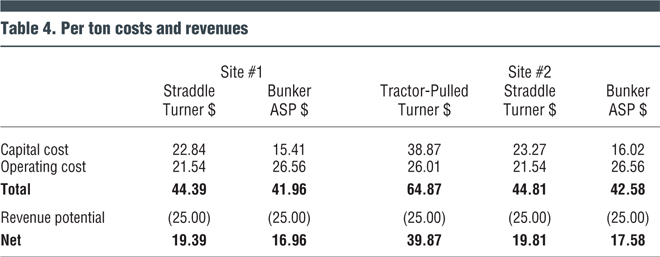

The capital cost estimates were converted to a “per-ton” basis by spreading the capital cost over 10 years of incoming tonnages. The operating costs were converted to a per-ton basis by spreading those costs over the tonnage coming in during a single year. The potential revenues from avoided transfer station costs and from product sales were converted to per ton costs based on a single year. Table 4 presents the alternatives on a per-ton basis.

The ASP alternative had slightly higher projected operating costs due to electricity to run the blowers and the cost of a separate mechanical mixing system. Only the two ASP alternatives had gross per-ton costs less than, or essentially equal to, the Transfer Station tip fee (which is $42.56/ton); the other alternatives have higher costs. Factoring in potential revenues, the per-ton costs drop significantly.

Service Charges

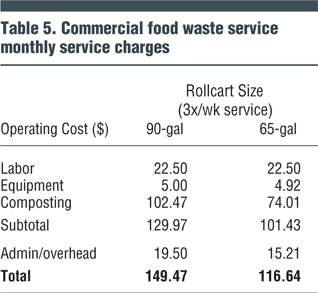

Assuming all diversion collection and composting costs would be borne by user fees assessed on customers, the service charges for commercial SSO collection service were calculated. This was based on the same methodology used to create the Commercial Dumpster Service Charges schedule currently in effect, but updated for actual 2013 costs incurred by the City. The $42.58/ton tip fee for an ASP composting facility at Site #2 was used for the composting costs, and it was assumed a rollcart would be collected three times per week. An administrative fee of 15 percent was included to account for program development and maintenance costs. These pro forma fees are summarized in Table 5.

There are some uncertainties in these estimates. For example, if the composting facility net tip fee (net of potential revenue) is used ($17.58/ton (lowest net fee in Table 4)), the monthly container fee drops to $80.28 and $66.67, respectively. Also, not all generators would need service 3 times per week (although some will need 5 day/week pickup).

It is unlikely that a commercial generator will subscribe to a voluntary program that will cost them more per month for solid waste management. If a restaurant or grocery diverts food waste to composting, then the volumes and weights of residuals that have to go into an existing dumpster or compactor are reduced. This offers the possibility that the dumpster could be down-sized and pick up frequency reduced to reflect the fact that putrescible organics are not going into that dumpster. This process of optimizing solid waste management collection infrastructure for a particular generator is called Resource Management Analysis.

To analyze this hypothetically, the existing Commercial Dumpster Service Charges were updated to 2014 conditions and compared to the Food Service Collection Costs in Table 5. For example, a commercial user generates 4 cy/week and has a 2 cy dumpster pulled twice per week (at a monthly cost of $130.91/month). If that user diverts 1 cy/week by using the 90-gal rollcarts picked up 3 times weekly (at a cost of $149.47), then there are 3 cy of MSW generated weekly that have to be removed. The user could go to a 1 cy dumpster pulled 3 times per week (monthly cost of $128.80) or a 4 cy dumpster pulled once per week (cost of $113.61/month). The savings from reduced pick up frequency or reduced size do not necessarily offset the additional costs of diversion to composting.

Next Steps

A more comprehensive evaluation of commercial food waste/SSO generators was recommended. This would include detailed waste audits of a representative sample of solid waste from several different types of generators, physical weighing and characterization into compostable and noncompostable fractions, and then determination of the optimum number and size of containers for each fraction. This determination could then be used to make up a pro forma invoice for routine service in a post-diversion timeframe for comparison to each commercial customer’s current solid waste management costs.

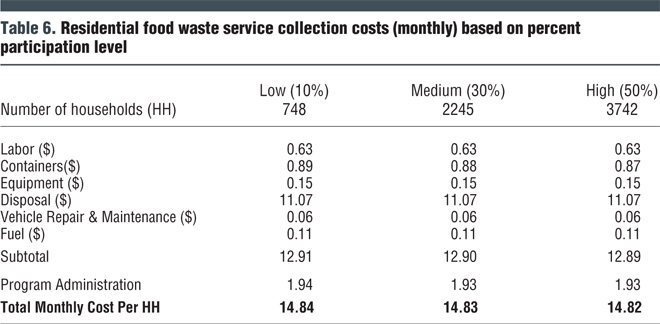

Although the City’s main interest is in a commercial-sector food waste/SSO diversion program, a similar analysis was done of residential households to give the City a more complete picture of the potential for food waste diversion. According to 2013 data from the Rolla Regional Economic Commission, there were 7,483 single-family households in Rolla. The economic analysis assumed three various levels of voluntary participation: 10, 30 and 50 percent. The analysis included labor time for picking up containers at curbside, capital cost of truck and containers, vehicle fuel, repair and maintenance, composting facility tip fee (gross of potential revenues) and program administration at 15 percent. The resulting monthly service charge would be about $14.84 as shown in Table 6.

While there is a great deal of interest in expanding SSO recycling by developing new diversion programs and new composting facilities, the costs for providing those services have to be considered. While this analysis was based on the premise that voluntary SSO diversion would be done at no net cost to the City of Rolla, the considerable costs of developing public sector independent diversion programs and composting facilities will likely need to be subsidized in some fashion for some time to come.

Craig Coker is a Contributing Editor to BioCycle and a Principal in the firm Coker Composting & Consulting (www.cokercompost.com), near Roanoke VA. He can be reached at craigcoker@comcast.net