Solar greenhouse, seasonal farm, and food scraps collection and management using microlivestock, insects and composting, are among the activities at educational facility.

Marsha W. Johnston

BioCycle August 2017

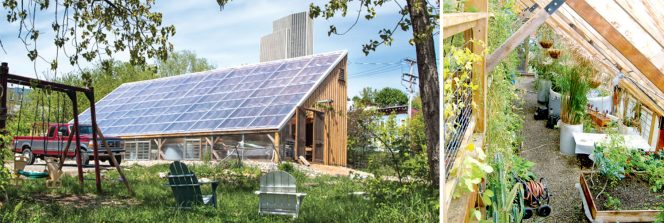

A greenhouse heated by passive solar and biothermal sources enables year-round food production. Photos courtesy of the Radix Ecological Sustainability Center

One of the educational nonprofit’s biggest programs is RUST (Regenerative Urban Sustainability Training), a weekend-long immersion course that nearly 1,000 people have taken to date. Based in part on Kellogg’s book, Toolbox for Sustainable Living, he, Pettigrew and other sustainability experts use hands-on activities and lectures to give attendees a “toolbox” of techniques and knowledge that promote self-reliance — everything from composting and soil remediation to how to build infrastructure with salvaged materials.

One of the educational nonprofit’s biggest programs is RUST (Regenerative Urban Sustainability Training), a weekend-long immersion course that nearly 1,000 people have taken to date. Based in part on Kellogg’s book, Toolbox for Sustainable Living, he, Pettigrew and other sustainability experts use hands-on activities and lectures to give attendees a “toolbox” of techniques and knowledge that promote self-reliance — everything from composting and soil remediation to how to build infrastructure with salvaged materials.To facilitate the Center’s programs, Kellogg and Pettigrew built a 20-by-60-foot solar greenhouse in 2011 as the main educational building. Sustainable systems on display today include:

• Bioshelter/Greenhouse: Heated by passive solar and biothermal sources for year-round food production;

• Bioremediation: Utilization of biological processes of naturally occurring organisms to remediate contaminated soils;

• Rainwater collection: Used for irrigation and urban water quality improvement;

• Renewable energy systems: Affordable wind, solar, and small-scale biofuels;

• Microlivestock: Sustainably raised chickens, ducks, geese and turkeys;

• Aquaculture: Aquatic plants and fish raised in a closed loop nutrient recycling system;

• Compost: Conversion of food wastes into soil-building fertilizer;

• Vermicompost: Use of worms to produce high-quality fertilizer from food wastes;

• Food forest and organic gardens: Intensive, sustainable urban food production;

• Apiculture: Raising bees for purposes of crop pollination and honey production.

Food Scraps Collection

Food Scraps Collection

In late 2010, before its official opening, Radix launched the Community Compost Initiative (CCI), a weekly organics collection service for Albany residents and businesses. The CCI members (about 35 to date) purchase a 2.4 gallon bin for their compostable waste, which Radix has been picking up with a car to compost on-site. Radix recently received a grant from the New York State Pollution Prevention Institute that is funding purchase of a solar-charged e-bike and trailer to do part of the collection. Residents also have the option of dropping food scraps off at the Radix Center. “Maybe later they will sign up for the collection service,” notes Kellogg.

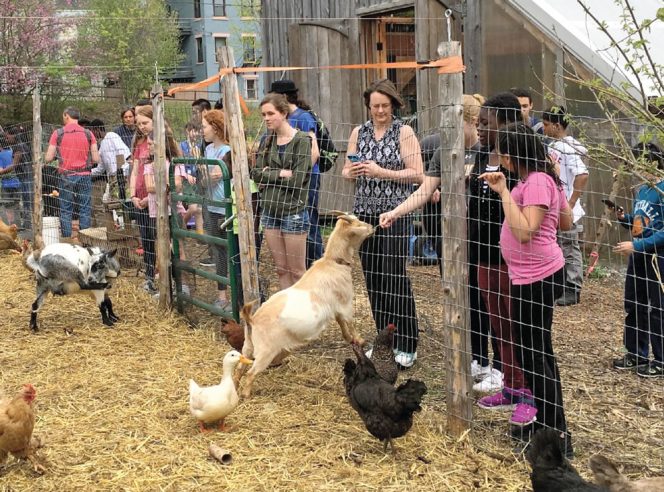

About two years ago, Radix added several goats to its urban farm, which opened up the type of food waste it could collect from its CCI members. “We will take vegetables, fruits, grains (breads, pasta, and kitchen leftovers that do not contain meat), egg shells, coffee/tea grounds, and a small amount of nonbleached paper napkins,” he says. “Goats are herbivores, so it is better for them not to eat meat.”

Albany currently has a ban on livestock, but Radix was granted an exemption for educational purposes. As chair of the urban agriculture subcommittee of the City of Albany’s Sustainability Advisory Committee, Kellogg says Radix has been actively lobbying to eliminate the microlivestock restriction, in part “because we believe chickens play an important role in composting.”

The Center feeds as much of its collected food material as possible to its microlivestock and to its mealworms. Whatever the animals do not eat (usually coffee grounds, fruit pits, napkins, etc.) is placed with wood chips from a local tree company in either passive wire composting bins or a biothermal composting system that heats the greenhouse in the winter.

Insect Farming

Radix also raises Black Soldier Flies (BSF) and mealworms for fish and chicken feed. In partnership with Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy (NY), Kellogg is running some experiments on whether Styrofoam (polystyrene) waste could be a component of their feedstock. Mealworms will eat polystyrene, he explains, as they have a gut bacteria that gives them a unique ability to break it down into carbon dioxide and a fecal pellet. “The Styrofoam has to be mixed with other food, and we’re waiting to determine that the mealworms definitely don’t have any toxicity before putting them back into the food chain,” explains Kellogg. “For now, we’re keeping them separate.”

Radix’s focus on youth education includes a Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) farm share run by high school students, who do the planting, harvesting and accounting, giving them urban agriculture and business skills. In the winter, Radix conducts farm education, introducing second graders to worm bins. “It’s important for city kids to have contact with worms, to understand the role they play as environmental engineers, and the difference between soil and lifeless dirt,” says Kellogg.

Finally, as a critical component to building healthy urban farms, Radix offers free soil screening for lead. On the past two Earth Days, residents brought up to 200 soil samples to the Center, where a Department of Health staffer uses an X-ray fluorescence machine to screen for lead. The City of Albany does not, however, have any lead remediation service, so residents with high levels of lead are simply advised to garden in raised beds. “When it comes to metals, the best we can do is isolate and immobilize their biological availability,” explains Kellogg.

Marsha W. Johnston is a Contributing Editor at BioCycle and an Editor at Earth Steward Associates in Arlington, Virginia.