Two-part series on western Canada starts with an update on British Columbia and Manitoba — including a report on the first year of Metro Vancouver’s organics disposal ban. Part I

Marsha W. Johnston

BioCycle June 2016

Harvest Power operates a high solids anaerobic digestion and composting facility, which processes organics from households, businesses and other generators in Metro Vancouver. Photo courtesy of Harvest Power

Part I of this article focuses on the provinces of British Columbia and Manitoba. Part II covers Alberta and Saskatchewan.

Metro uses ads animated by humanized food scrap characters for public education in its bus and transit shelters, as well as in its social media.

Metro Vancouver, British Columbia

Canada’s third-largest metropolitan area, Metro Vancouver (Metro), manages approximately 1.3 million tons/year of waste from 21 municipalities, one Treaty First Nation, and one Electoral District. Total population served is about 2.5 million. Landfill tipping fees are over C$100/metric ton, which have been a driver for diverting food scraps from disposal.

Metro Vancouver began to consider an organics disposal ban as early as 2008, starting with consultation and public engagement from 2008-2010. That led to planning, surveys and continuing consultation in 2012-2013. In a composition study of the waste stream in 2013, Metro found that 36 percent was compostable organics, including food waste — a good indication that an organics recycling program was needed. “Large grocers and restaurants were already starting to voluntarily source separate organics,” notes Marian Kim, Metro’s lead senior engineer of solid waste services.

In the Integrated Solid Waste and Resource Management Plan developed during 2008-2010, Metro Vancouver had set a diversion goal of 70 percent by 2015, and an aspirational goal of 80 percent diversion by 2020. The agency knew that a key tool to achieve those higher rates would be materials disposal bans that apply surcharges to loads coming into transfer stations and other disposal facilities with amounts of banned material greater than allowed. It created bans on green waste, cardboard, paper, newsprint, and other recyclables.

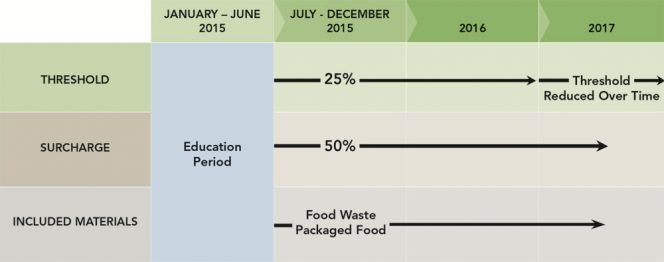

An organics disposal ban targeting all food and packaged food waste was rolled out by Metro on January 1, 2015, taking a phased approach. The first six months of the ban (through June 30, 2015) were an educational period with no penalties. Financial enforcement began on July 1, 2015 with a 50 percent surcharge levied on the normal tipping fee for loads with over 25 percent organics in the waste (see box). “The surcharges are applied to the hauler, so the hauler has to identify who had the load, but they typically spread it over all [customers],” says Kim.

Just over a year after the organics ban went into effect, Metro Vancouver saw an 8 percent drop in the organic composition of its garbage, quarterly increases in organic waste processed, extremely high compliance, and huge increases in public awareness and access to food scraps recycling. On an organics ban implementations webinar sponsored by the American Biogas Council in mid-February (based on a session at BioCycle REFOR15), Kim was uniformly positive in her assessment of Metro’s policy change. “We are very encouraged with the results we’re seeing,” she noted.

To educate the public, Metro used ads animated by entertaining, humanized food scrap characters saying “food isn’t garbage” in bus and transit shelters, as well as online and in social media. The artwork is available for anyone to use. Last October, it added more food scrap characters such as clamshell packaging. How-to guides, videos and other materials were translated into languages commonly spoken in the region. “Realizing that icons and colors are universal languages, we also tried to standardize our various recycling program colors and signage throughout the region,” Kim explained.

Metro also partnered with a provincial agency to develop a food donation guide that is available on its website. Further, it has been working with the Zero Waste Council on trying to clarify food expiration and “best by” dates.

The organics ban generally received a lot of media attention, she added, with two major spikes in coverage — one at the debut on January 1, 2015 and one on July 1, 2015. Phone calls from the public to the recycling hotline spiked at exactly the same times (January 1 and July 1). In July, Metro received calls from some customers — primarily commercial and multifamily sites — whose private hauler had passed along penalty surcharges for excessive banned materials. “We had customers angry about the financial penalties, but it raised awareness pretty quickly,” Kim noted. She added that after surcharges were levied, the compliance level for the organics ban was extremely high, with an average of only 12 loads per month having over 25 percent food waste, which represent well below one percent of total loads being received at the facilities.

Hoping the ban would provide a big jump in diversion from its 61 percent rate in 2014, Metro conducted another composition study of regional waste late in 2015. The study showed a drop in compostable organics to 28 percent, from 36 percent in 2013. The percentage change is estimated to comprise an approximately 70,000 tons annual decrease, which it attributes to the organics ban, Kim explained. Not surprisingly, she added, the organics processed by composting facilities in the region went up in every quarter of 2015 compared to previous years. In 2015, the region’s private licensed composting facilities reported an annual increase of approximately 60,000 tons, over 2014 quantities processed.

A telephone survey of businesses and residents in multifamily dwellings in April-May 2015 found that between 59 and 81 percent of respondents had access to food scraps recycling. An average of 73 percent of the hospitality sector had access, almost tripling the 25 percent access that the sector reported in a 2012 survey. Multifamily dwellings were on the low end of survey respondents, at 63 percent access, Kim said, adding that more and more multifamily buildings are coming on board with collection programs.

Metro Region Processing Infrastructure

Metro Vancouver regional solid waste facilities comprise those it operates, which include five garbage transfer stations, one waste-to-energy facility, and one soon-to-close landfill, and those operated by the City of Vancouver, which include one transfer station and one landfill. Metro Vancouver sets the rules for waste management but does not provide collection services. One of those rules, Kim noted, is a guideline discouraging use of plastic bags in organics collection containers because private composting contractors have difficulty determining which plastic bags are compostable and which are not.

Harvest Power operates a high solids anaerobic digester (AD) with capacity of 40,000 metric tons/year, and a covered aerated static pile (CASP) composting site where it receives municipal and commercial postconsumer organics and “a few truckloads a week of expired or unusable packaged food,” explains Louise Roxby, sales manager. The packaged food, such as Tetra Pak packaging, included in the organics ban account for less than 5 percent of the total food waste received, she notes. Harvest uses a Scotts Turbo Separator 3096 to depackage those types of materials. The postconsumer commercial organic waste and depackaged preconsumer food go into the AD, accounting for approximately 20 percent of Harvest Power’s total volume in Vancouver. Organics collected at curbside, including household yard trimmings and postconsumer food waste, go directly to the composting operation.

Roxby says the company charges more for any municipal loads with over 10 percent of compostable bioplastics, including service ware, but has always allowed commercial haulers to line their 21-gallon bins with compostable liners. The challenge, she explains, is that even plastics certified as compostable in 180 days are contamination for Harvest Power’s 90-day composting process. “Compostable plastic bags go through our [compost] processing, and whatever is left is screened out,” notes Roxby, adding that Harvest Power knew contamination would increase when it began taking food waste. Nonetheless, contamination averages between 1 to 5 percent, though it can go as high as 10 percent. The company has instituted a grading system, with four grades of incoming feedstocks, from Grade 1 (clean) to Grade 4 (reject), and correlating fees that nearly double between 1 and 3. As a result of the organics ban, Roxby adds that Harvest Power’s compost production has increased and she expects more than 200,000 cubic yards will be sold in 2016.

Metro Vancouver encourages large grocery customers and licensed composting partners to direct packaged food waste to businesses looking for preconsumer food waste, such as Enterra Feed Corp. in Vancouver. Enterra uses preconsumer food waste to feed black soldier fly larvae that are harvested for fish food.

With its successes in 2015, and to provide additional time for the region to adjust to the organics disposal ban, Kim explains Metro Vancouver decided to continue with the 25 percent allowable amount of food waste in loads arriving at disposal facilities for 2016. She adds that the number of surcharges would not increase substantially even if it did decrease the allowable threshold of food waste. It will be reviewed in mid-2016 for 2017.

Interior British Columbia

The interior section of British Columbia (BC) is processing primarily leaves and yard trimmings and some biosolids, but not much food waste, notes Scott Gamble, organic waste specialist with CH2M, who has worked on diversion projects in Canada for years. Kelowna, one of interior BC’s larger population areas, has two of the region’s largest facilities, one exclusively for yard trimmings, and the other composting biosolids from the city’s wastewater treatment plant.

Marcia Dick of Waste Naught BC collects food scraps in Kamloops, BC, using an electric bike and trailer. A Joras in-vessel composter (right) is used at a community garden to process the food scraps. Photos courtesy of Waste Naught BC

Dick started out using the Joras NE400 in-vessel composter at one community garden; at a larger garden, she is planning to utilize aerated static pile composting. An avid biker, Dick decided to haul BCLC’s food waste twice a week in bins on her bike trailer, which she did from October to April. More recently, she alternates between bike collection, and using a pickup truck.

Manitoba

In 2009, the Province of Manitoba established a Waste Reduction and Recycling Support (WRARS) levy, which required all landfill owners, whether private or municipal, to charge C$10 (US$7.90) for every metric ton of waste they accept. “Basically, you can’t put anything in the landfill without paying [the levy],” notes Jim Ferguson, Senior Manager of the WRARS Program for Green Manitoba.

Kept separate from Manitoba’s general revenue, the WRARS fund generated C$9.8M (US$7.75M) in 2014. “Out of that fund, 80 percent is rebated back to municipalities for residential recycling diversion, excluding organics,” Ferguson explains. “The remaining 20 percent supports other projects and programs, including C$1M (US$791,000) for the Manitoba Composts program, which began in 2014.”

Manitoba Composts funding is allocated in the form of incentive payments to municipal and private composting facilities that meet the program criteria for processing organics. “Composting facilities must have an environmental license, analyze their compost using the Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment (CCME) compost quality guidelines, have a trained facility operator and process eligible organic material (leaf, yard and food waste),” he adds. In addition, composting facilities processing over 2,500 metric tons/year receive C$10 (US$7.90)/metric ton, while smaller facilities are eligible for up to C$25 (US$19.75)/metric ton.

“The Manitoba provincial government is pushing hard on organics diversion,” Gamble of CH2M notes. In its first year, Manitoba Composts registered 8 sites and 42,900 tons of eligible organics processed, including Winnipeg, which reported processing 29,750 metric tons of eligible organics. Facility operators received almost $500,000 in compost support payments. The goal, says Ferguson is to divert 100,000 metric tons of organics annually from landfills by 2020, which likely will lead to some new facilities being established and expansion of existing ones.

This appears to be happening already, according to the Green Manitoba annual report: “Since the announcement of the Manitoba Composts program, there has been an increasing interest from a number of municipalities, private companies and social enterprises to offer green bin collection as well as processing.” Manitoba Composts Program funds also are used to support training, research and market development for composting, as well as projects that develop composting infrastructure and equipment.

Winnipeg built an outdoor yard trimmings composting facility to process 25,000 metric tons/year. A pilot-scale biosolids composting project is located at the same site. Photo courtesy of City of Winnipeg

Winnipeg (pop. 664,000), the capital, is the largest municipality in Manitoba — about 70 percent of the province’s total population. In 2011, City Council approved biweekly residential yard trimmings collection from April to November. Two years later, Winnipeg built an outdoor windrow yard trimmings composting facility to process 25,000 metric tons/year. A pilot-scale biosolids composting project is located at the same site. It opened in May 2015 and processed 3,500 metric tons of biosolids in 2015. The biosolids compost is used for finish cover on Winnipeg’s 800-acre landfill.

In its first year of operation, the yard trimmings facility composted about 23,200 metric tons, and exceeded its capacity in 2014, at 29,800 metric tons. In 2015, the city collected 33,000 metric tons. “It’s a great problem to have too much yard waste,” says Randy Park, the city’s waste diversion supervisor. “We are managing the operation more stringently to use the site as efficiently as possible, and are in the midst of devising a strategy that will look at the entire organics stream.”

Winnipeg has a goal of diverting over 50 percent of its landfill waste by 2020, from just over 30 percent currently. The only way to get there, notes Park, is with some kind of weekly source separated organics (SSO) collection and composting. “Right now, the city has no residential SSO program,” he says. “There is some private collection from commercial sites and restaurants, but it is a low volume, subscription service. We are looking at introducing curbside collection of organics to all single-family dwellings.”

In mid-April, Winnepeg’s Water and Waste policy committee tasked Park’s department to prepare a detailed plan for consulting the public on what type of curbside SSO program it would like to see — whether just vegetative scraps, or all food waste, or food waste and pet waste. The plan will be presented to the council sometime in the summer. Park explains there is political support for developing the organics strategy, but that there will be debate over its implementation, “most likely around cost and how to fund it.” In the meantime, the yard trimmings composting and biosolids pilot program will continue.

It is too soon to speculate on a target rollout date for a curbside program in Winnipeg, he adds. “We’re not there yet. When I give a presentation [on organics diversion] I always say, `One of the best things our forefathers did was to secure 2,200 acres for landfill and one of the worst things they did [for diversion] was to secure 2200 acres for landfill’.”

Marsha Johnston, editor of Earth Steward Associates, is a Contributing Editor to BioCycle.