Why progressive recycling based on how residents pay for trash dramatically reduces waste disposal.

Neil Seldman

BioCycle October 2018

Pay As You Throw (PAYT), a proven global waste metering system, is the vital first step to reaching Zero Waste. PAYT, or unit-based pricing, is the single most effective way to educate and motivate residents to reduce, reuse, recycle and compost. After all, what is the difference between unit-based pricing for electricity, water and/or natural gas in our households and doing the same for garbage?

Pay As You Throw “Clip Art” from the U.S. EPA Archives, circa 1990s.

• Per capita waste generation in the household sector in PAYT cities is close to half that of non-PAYT cities. In 2015, 43 percent of Massachusetts municipalities operated PAYT programs, according to an article in Commonwealth Magazine, and the non-PAYT municipalities threw away 55 percent more residential waste per capita than the PAYT municipalities.

• PAYT programs are a boost to backyard and community scale composting which reduces the volume of material landfilled or incinerated and puts valuable nutrients back into the soil. Further, for every 10,000 households composting at home, between 1,400 and 5,000 tons/year could be diverted from curbside collection with potential savings in avoided disposal costs alone ranging from $72,000 to $250,000 (Platt and Fagundes, 2018).

• A recent study from MIT (Pollans, et al, 2017) concluded, “A notable factor that predicts adoption of curbside food scrap recycling, other things being equal, is the existence of PAYT trash collection. This strongly suggests that such programs get residents in the habit of actively managing their trash disposal in response to financial incentives — and, as such, makes it seem less burdensome to separate food from other kinds of trash.”

• PAYT pays off in budgetary savings. Decades of operational research prove PAYT is a sound fiscal and environmental policy decision. In New England, there are over 500 existing programs that have successfully reduced trash volumes and saved those communities money. Research conducted by WasteZero about the impact of Pay-As-You-Throw systems on residential trash collection in Southern Maine offers further validation based on 2017 collection data from 20 communities. In a head to head comparison PAYT cities had 356 lbs/capita of waste vs. 645 lbs/capita in cities without PAYT and lower trash volumes mean lower disposal costs.

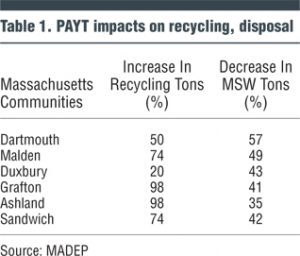

• Additional data from the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (2013) indicate impressive results in increased recycling and reduced overall waste from PAYT cities and towns (Table 1).

Measuring Per Capita Disposal

Data gathering is critical but data interpretation is key. For the most part, municipalities only have direct control over the residential waste generated from single-family homes (4 units attached and under), so it’s important to track the residential sector separately from other waste in order to benchmark the success of any given program. Surveys by consultants often do not go deep enough to determine actual impacts of various waste reduction initiatives by stream or sector. Using diversion rates based on a random year, measuring set out rates, or relying on recycling rates does not provide a consistent standard because waste stream materials are constantly evolving and home composting as well as many reuse streams cannot be accurately tracked.

The key is to track what is still being disposed. Residential per capita disposal is the most reliable metric as it gives the most realistic picture of what volume of trash a residential collection systems produces regardless of size. A comparison of systems using this performance metric provides clear evidence that a PAYT pricing system is the single most effective way to reduce residential waste. That said, it is important to understand that not all trash-metering programs are equally effective. Of the 7,000 towns and cities that the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency categorizes as PAYT, only an estimated 2,000 have the features that are needed for success. Most have a variable price system, but in many cases the differential rates do not provide sufficient incentive to change behavior and purchasing habits.

Researchers sometimes assume that just because a city has a tiered pricing system it will reduce trash. However, when tiered systems are not priced correctly it can have the opposite effect where residents are prompted to select a larger container because it seems like a better value.

Proportional Rates

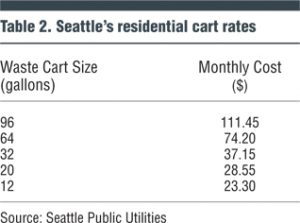

Rates have to be proportional. If household waste is reduced two-thirds by recycling, backyard composting and donating to charities or thrift stores, the price structure should reflect these actions through savings. When rate differentials are not proportional, waste reduction programs have little if any impact. Conversely, proportional programs provide better waste reduction. For example, Seattle’s monthly differential cart rates for residential services are quite dramatic (Table 2). The city is one of the best performing systems of this type. Its residents throw away 369 lbs of waste per capita and have access to weekly curbside recycling, yard trimmings and food scrap collection.

An example of an even higher performing system is the city of Portland, Maine, which ranked number one in ILSR’s research, with 268 lbs of waste per capita thrown away. Portland has a bag-based PAYT system; a 15-gallon bag is $1.35/bag and a 30-gallon bag is $2.70/bag. The city offers weekly recycling and seasonal yard trimmings collection to its residents.

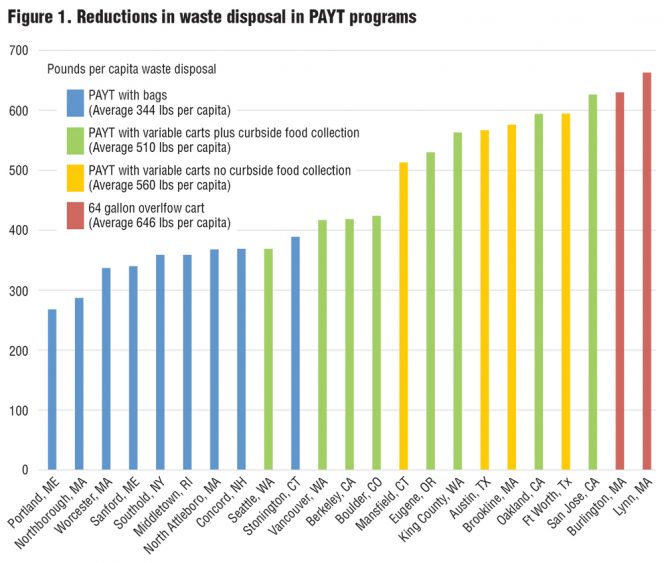

The industrial city of Worcester, Massachusetts, which uses a bag as the unit base, has lower residential per capita waste generation than Austin, Texas or Berkeley, California, where a cart is used as the unit base. Of the 37 municipalities that ILSR reviewed, 14 were programs where the cart size acts as the metering unit (averaging 475 to 568 lbs. of waste per capita depending on if regular curbside food scrap collection was available). Ten were programs where the bag size acts as the metering unit. These programs average 344 lbs. per capita disposal (Figure 1).

Recent Lessons Learned

Generally, problems with unit-based PAYT pricing are either nonexistent or easily overcome based on extensive experience in jurisdictions across the U.S. PAYT implementation requires careful planning to address the pricing mechanism per unit of trash (bag or cart fee), the physical conversion to the new system, which includes distribution of bags or carts, and a proactive public education campaign.

ILSR’s research highlights a number of lessons learned with PAYT program implementation and management. These include:

• It is a common practice of nearly every city in America to establish collection standards and establishing rules for PAYT program is no different.

• Existing enforcement procedures are deployed, generally with no increase in costs when transferring to a PAYT system. PAYT may require a conversion period but does not require additional staff for enforcement. Most communities easily reach 98 percent compliance after the initial implementation period.

• Illegal dumping is not a major barrier. The National League of Cities’ Sustainable Cities Institute notes “there are usually concerns that PAYT programs will lead to an increase in illegal dumping. However, most PAYT communities have found this not to be the case especially when PAYT is promoted alongside other legal methods of waste disposal, such as curbside recycling and yard trimmings composting.”

Adds Bob Gedert, former director of the Austin (TX) Department of Resource Recovery and that city’s Zero Waste program: “Illegal dumping is a transitory issue that should not prevent a community from benefitting from the long-term positive effects of PAYT.”

• Low income residents are allegedly adversely affected by a unit-based system. Yet these systems have shown to work well to help households control costs. Municipalities can transition to unit-based systems with reduced rates or free bags for low-income residents. Most communities offer education in low-income communities, creating an opportunity to reach out to these residents with other city services. Bags are a more transparent, equitable system where the renter population is high because the tenant is deciding how much they pay based on bag size each week, instead of having a landlord choose a large container and bury the cost in the rent.

• Program administration can have some cost. In bag programs, the cost of distribution and billing are typically absorbed by the manufacturers and calculated into bag fees yielding limited additional management expense for cities. Many retailers and grocers will offer the sale of the bags at no upcharge to the city, as a goodwill program. If the city chooses a cart program there are some additional administration fees because all households must be billed regularly for their selected cart size, and cart inventory must be available to switch out for smaller and larger carts as residents move and additional waste reduction programs become available.

In conclusion, it’s clear that a trash metering system incentivizes residents to think twice about what materials can be reduced, reused, and recycled. When families pay for only what they generate, their behavior change not only saves money at home but moves valuable resources out of the waste stream and into the supply stream creating regional jobs and promoting a circular economy, and significantly reducing their carbon footprint.

Neil Seldman, Ph.D, directs the Institute for Local Self-Reliance’s Recycling and Economic Growth Initiative. He specializes in helping cities and businesses recover increasing amounts of materials from the waste stream and add value to the local economy through new processing and manufacturing facilities.