Developing productive and meaningful public relationship programs is critical to resolving odor challenges at organics recycling facilities. Part V

Craig Coker

BioCycle November 2012, Vol. 53, No. 11, p. 22

No matter how well-planned, well-sited or well-run, composting facilities are always at risk for an off-site odor episode that can create challenges such as negative publicity, regulatory intervention, and the potential for lawsuits. How a composter responds to odor episodes can significantly influence the facility’s public (and investor) support, financial performance, regulatory interactions, employee jobs and much more.

One composter this author knows responded to off-site odor complaints from subdivisions recently built adjacent to his composting facility with “The heck with them, we were here first.” Needless to say, that is not how one wins “hearts and minds.” Part V of BioCycle’s Odor Management series examines appropriate measures for dealing with public outrage, and profiles two composting facilities that have implemented calming measures.

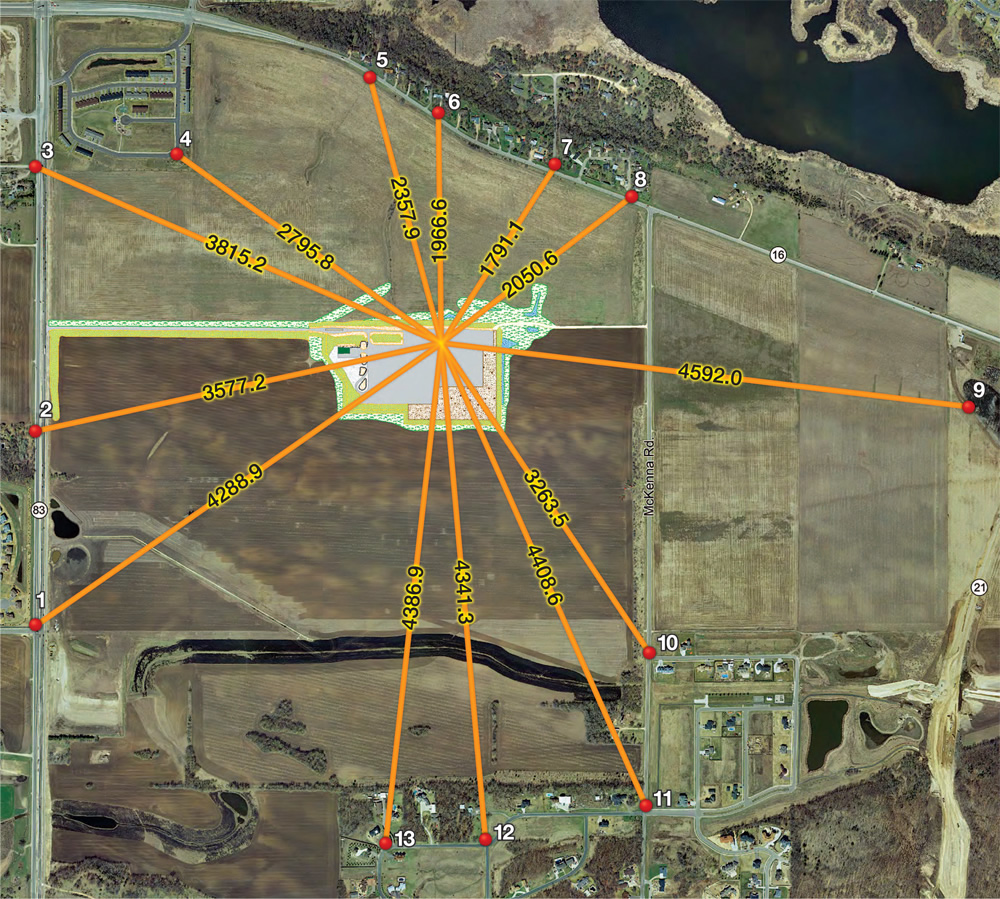

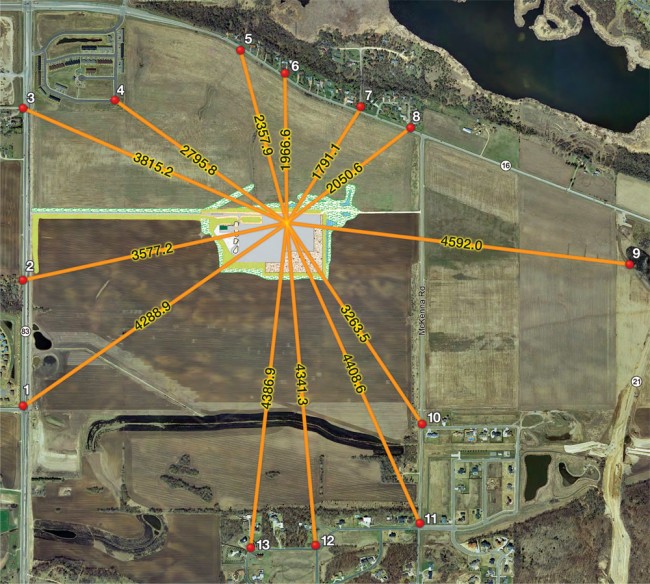

Lineal distances (in feet) to odor survey stations from the Mdewakanton Sioux Community organics recycling facility are shown.

Public Perceptions Of Odors

In general, air quality has improved considerably over the past several decades, which has reduced the levels of odors in outside air. Strides also have been made in reducing the amount of indoor odors. One unintended consequence of this improvement in air quality is that more people are intolerant of odors. “This apparent paradox is related to a concept from the field of cognitive psychology called ‘signal detection,’” noted Pam Dalton, Ph.D., a faculty researcher at the Monell Chemical Senses Center (see “How People Sense, Perceive, and React to Odors,” November 2003). “As we have reduced the odor background level (or what in Signal Detection Theory would be called the noise level), the presence of an intrusive odor signal becomes more apparent.”

Another contributing factor is that, historically, people have associated bad odors with diseases. “Long before we understood that germs were the basis of disease transmission, there was this concept, called the ‘miasma theory’, that it was the odors associated with sickness and disease that were causing people to become ill, and that if they could remove those odors, they could remove the source of the disease,” said Dalton. This association persists to this day. Many people believe they have suffered real health impacts from odorous air. The most frequently reported health complaints include eye, nose and throat irritation, headache, nausea, diarrhea, hoarseness, sore throat, cough, chest tightness, nasal congestion, palpitations, shortness of breath, stress, drowsiness and alterations in mood (Schiffman, 2000).

“People’s reaction to odor and their beliefs about the effects from odor are influenced by a diverse set of factors, including personality traits, personal experience, and information or social cues from the community and media,” said Dalton in the 2003 BioCycle article. “The reaction people have to odors is not simply due to the sensory impact but is also shaped by the attitudes and expectations that an individual brings to an odor experience, which has strong implications for building understanding and relationships with neighbors.

“In one experiment we conducted at the Monell Center, we exposed two groups of volunteers to an odorant, which was acetone, or nail polish remover, but we included in each group a paid actor. In each group, the actor either responded positively to the odor (e.g. helps breathing, increases alertness), or negatively (e.g. irritates eyes and nose, causes coughing). After exposure to an odor, most people adapt to a constant odor level, which decreases sensitivity to the odor and to its perceived intensity. In the negative bias group of volunteers (where the paid actor was complaining), that adjustment did not happen. People claimed significantly more adverse physical health effects, and some reported coughing although none of them actually did.”

This phenomenon of the social influence on people by the actions of one, or a few, highly agitated individuals offers insights into how groups of individuals exposed to a composting facility odor may jointly complain, but individually behave in a more rational manner. The author observed this group dynamic at a civic association’s odor complaint meeting regarding a biosolids composting facility in Maryland. The association members were aggressively agitated in the group meeting but significantly more relaxed and rational in one-on-one discussions both before and after the meeting.

During the period 1999 through 2002, the Water Environment Research Federation sponsored work to understand public perceptions of biosolids recycling (see “Public Perceptions of Biosolids Recycling,” April 2005). While focused on land application of biosolids, that work led to a greater understanding of how people perceive risk of waste management programs, which is applicable to composting facilities. Fear of the unknown or the exotic is a stress driver that can trigger perceived (or, according to Schiffman, real) health impacts believed to be attributable to the project. An offsite odor episode can be easily construed as unknown or exotic. The negative reaction to the odor, with the associated fear of breathing chemically-contaminated air, creates a perception of risk that becomes that person’s reality, and is likely negative and lasting. This “perceived reality” is often reinforced by information gathered from internet sources and is based on a combination of perceived hazard and expressed outrage. That perceived reality of a person complaining about an odor episode is where the dialogue must start on restoring public trust in a composting operation.

Developing Public Relationship Programs

Composters need to develop public relationship programs, not just public relations or outreach programs. A public relationship program is based on two-way communication, so listening is every bit as important as outreach. Listening begins with understanding the neighbors’ “outrage factors” (Beecher and Goldstein, 2005). An outrage factor influences perception of risk and includes: involuntary, industrial, uncontrollable, exotic, unknowable, unfair, dreaded, untrustworthy and similar descriptors. Building a public relationship program requires steps to reduce, or address, the outrage factors, which is the practice of risk communication. This includes initiatives such as having an educational open house and establishing a “Neighborhood Liaison Committee” of both alienated and impartial neighbors and reviewing planned and implemented changes to address odor complaints. By helping impacted individuals understand the intricacies of composting, and providing a voice in evaluating alternatives, something “exotic” and “uncontrollable” becomes something that is known and more controllable, thus addressing outrage factors.

Composting facility managers need to resist the counterintuitive reaction that developing a public relationship program involves surrendering control over the facility or outcomes. Once an off-site odor episode has occurred, and complaints have been registered, there is simply no way to “stay under the radar.” It will undoubtedly be unpleasant to deal with angry neighbors, but by giving people time to understand information, establishing two-way dialogue, treating them with respect and, most importantly, listening without judgment, the facility’s management can assure the majority of neighbors that planned corrective actions will work. There will always be people who will never be satisfied until the composting facility is shut down, but a primary goal of any public relationship program is to satisfy the majority of neighbors, elected and regulatory officials and the media, that a facility’s odor mitigation strategy is, or will be, effective. Also, provide tools, such as hot lines to report odor impacts, staff equipped to investigate complaints and measure odor levels and regular neighborhood liaison committee meetings to ensure the facility operator’s responsiveness.

In short, earning people’s trust starts with credibility. Neighbors have to believe in the credibility of the staff, the consultants and the environmental regulators. Credibility is earned by the composter’s willingness to be open and transparent in its decision-making processes, to conduct or acquire information from research that is credible, legitimate and salient, and to develop the infrastructure for independent oversight of corrective actions.

Using Metrics to Track Progress

As communications are qualitative processes, it can be difficult to determine effectiveness. But measuring effectiveness is an important step toward monitoring, evaluating and improving public relationship programs. Composters should develop a quantitative set of metrics to measure what the public relationship program does and give insight into how well it is being implemented and performing. Metrics will not measure increased or decreased outrage and trust directly. A compost manager can only focus on the process, as the process can be controlled, but not the outcome.

Metrics should have these characteristics: Measurable, Easy, Timely, Repeatable, Insightful and Controllable (Sullivan, 2004):

Measurable: A metric that can be quantified, like the number of open houses a facility offers each year.

Easy: Simply to understand and apply, like measuring the length of time for management to personally respond to an odor complaint.

Timely: The process is being measured as close to real-time as possible. An example would be developing information systems that track wind speed and direction on a continuous basis on-site as opposed to relying on periodic observations from a nearby airport.

Repeatable: Establishing fixed odor monitoring points for repeated measurements that are reported to the community.

Insightful: Provides a deeper understanding of how the process is working. For example, an odor complaint log should record more than the person’s name and phone number; it should record information about the nature, duration and intensity of the odor.

Controllable: Measures something that is controllable, such as the number of community meetings held, but not the number of attendees at each meeting.

Examples From The Front Lines

The Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux Community owns and operates a 35,000 tons/year open-air turned windrow composting facility on tribal lands southwest of Minneapolis (see “Tribal Community Launches SSO Facility,” May 2012). The facility handles primarily yard trimmings and food scraps, although it takes in residuals like shredded playing cards from the tribal casino. Even though it is situated on tribal lands and is not subject to regulatory oversight by the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA), the facility operates as if it were in MPCA’s jurisdiction.

The composting facility opened in mid-2011 and started getting odor complaints in the spring of 2012. “We’ve received about 60 to 70 complaints, all from our neighbors to our north, where the homes are 1,800 feet or so from our facility,” says Mike Whitt, the Community’s Natural Resources Manager and the Manager of the organics recycling facility. As a result of the complaints, Whitt hired a professional industrial hygienist and implemented an odor monitoring protocol of repeated measurements of odors using a St. Croix Nasal Ranger. (Aerial photograph on page 22 shows the site and the monitoring stations that staff routinely monitor.)

The Region of Peel curing facility ran into a firestorm of odor complaints when it first opened using an open-air windrow system. Establishment of a public liaison committee and extensive outreach and education, plus installation of a GORE cover system, has yielded positive results. Photo courtesy of Region of Peel

Getting the residents to accept quantitative data has been challenging. “I’ve shared the wind speed and direction data and the Nasal Ranger monitoring results with our neighbors and they claim we’re making this up,” he adds. “I had one person claim we came out to do monitoring and then went back to the facility to flip some switch that turned the odors back on.” The Community did have an open house in October and Whitt was pleased that almost 100 people showed up. “We had three of our neighbors visit during the open house, including one man who has been particularly difficult,” Whitt says. “I was happy to see that he took the time to come over to see us and learn more about what we’re doing. I think over time, we will be able to get in front of this issue.”

Another example is the Regional Municipality of Peel, a community of 1.3 million people west and northwest of Toronto, Ontario, Canada. The Waste Management Division of the municipal government built a 60,000 tons/year enclosed tunnel reactor composting system in 2006 at its Integrated Waste Management Facility in Brampton. After approximately 7 to 10 days, the material is removed from the tunnels and brought to the Peel Curing Facility in Caledon. Initially this material was being cured in open air windrows. Shortly after the tunnel reactor/curing system came on-line, Peel ran into a firestorm of odor complaints from citizens in the first year of operation.

“It was a pretty ugly process to start with,” says Larry Conrad, Manager of Waste Operations for Peel, speaking of their initial public outreach efforts. “Our Commissioner stood up in front of the audience and said we would close the facility until we could figure out how to fix the problem. That started a long process of operational and technology modifications to fix the problems and we reopened in 2009.” One of the improvements was to install a Gore Cover System over the curing windrows. Material is now cured under the covers in 24 windrows for 6 weeks and then screened to produce the finished compost. Also during this period, Conrad implemented a public relations program that included open houses and tours, developed a daily odor/noise/dust monitoring protocol, and set up a Public Liaison Committee. The minutes of the Public Liaison Committee meetings are provided to the Waste Management Subcommittee as well as to all of the Council members for information purposes.

The nuisance monitoring protocol involves staff going out 3 times/day, everyday, to personally monitor odors, dust and noise at 10 locations around the curing facility. The Region of Peel uses a private contractor to manage a web-based meteorological monitoring system to compile data from several meteorological monitoring stations at Peel facilities. Its monitoring protocol begins by noting the weather conditions, and then traveling to each location to monitor the presence and intensity of noise, dust and odors. The monitoring forms include the ability to record the presence of odors, noise and dust from sources other than the composting facility.

The Liaison Committee consists of four citizens and the Peel Regional Councillor for the area where the facility is located. The Committee meets with Waste Operations staff quarterly. Each meeting has a standard agenda, which includes a review of an activities tracking spreadsheet, operations reports, environmental monitoring activities, compost marketing activities, a discussion of any correspondence with the community, and a discussion of any upcoming planned activities or improvements at the facility. The Committee gets reports on the number of windrow turnings and truck movements, quantities of materials received, in process and shipped, and any odor complaints received. Committee members meet with their neighbors to share the information provided by the Region of Peel and report back any questions. “While many of the neighbors were not interested in learning how our facility is operated, the members of our Liaison Committee are very interested in composting,” says Conrad. “It has been a steady process of educating, rethinking and recharging to improve our relationships with the community, but it has paid off, in my view. I’m pleased that we’ve only had two odor complaints so far this year.”

Craig Coker is a Contributing Editor to Biocycle and a Principal in the firm Coker Composting & Consulting (www.cokercompost.com), near Roanoke VA. He can be reached at cscoker@verizon.net.

References

Beecher, N. and N. Goldstein, “Public Perceptions of Biosolids Recycling”, BioCycle, Vol. 46, No. 4, p. 34, April 2005.

Dalton, P., “How People Sense, Perceive, and React to Odors”, BioCycle, Vol. 44, No. 11, November 2003, p. 26.

Goldstein, N., “Neighbor-Friendly Odor Management”, BioCycle, Vol. 47, No. 3, March 2006, p. 43.

Schiffman, S., et. al., “Potential Health Effects of Odor from Animal Operations, Wastewater Treatment, and Recycling of Byproducts”, Journal of Agromedicine, Vol. 7, No. 1, 2000.

Sullivan, M., et. al., “Using Metrics to Track Progress of Community Outreach Programs”, Chemical Engineering Progress, American Institute of Chemical Engineering, Dec. 2004.