Ohio University’s in-vessel composting facility processes about 100 to 120 tons/month of food waste and amendment during the academic year.

Dan Emerson

BioCycle July 2018

In 2009, Ohio University in Athens, Ohio, used a $350,000 grant from the Division of Recycling and Litter Prevention within the Ohio Department of Natural Resources to purchase an in-vessel composting system with capacity to process 2 tons/day of food waste and other organics generated by the university. Several studies done before the system was installed indicated that 30 to 40 percent of the university’s waste stream was organic material. An additional $35,105 for a 10 kW solar array was awarded from the Ohio Development Services Agency’s Energy Loan Fund grant program.

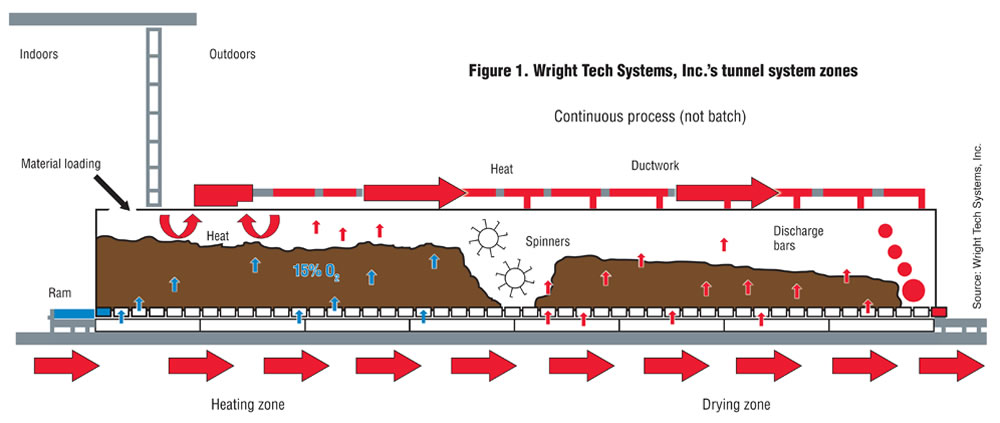

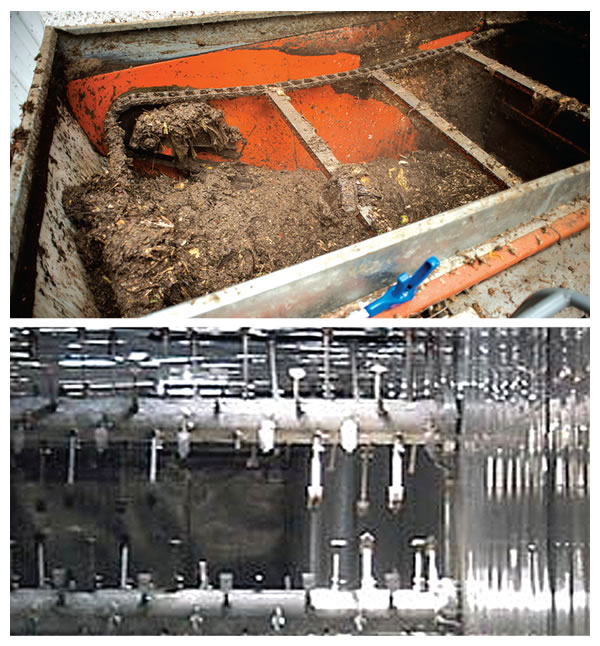

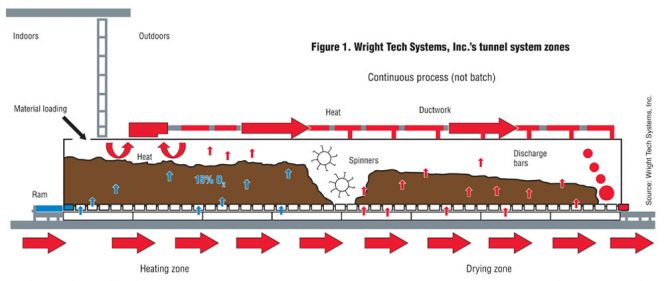

The tunnel utilizes trays (top) that move the materials through the composter. Spinners (bottom) homogenize, agitate and restack material on the trays between the active composting zone and the “drying” zone.

Ohio University prepares food at a central location and then distributes it to three dining halls. Both pre and postconsumer food waste are collected Monday through Saturday (twice a day) in 65-gallon, lidded carts from the central kitchen, three dining halls, several small coffee bars and a cafe run by health professionals. A 24-foot box truck is used for collection; clean containers are “swapped out” for the full ones.

The University spent several years testing a variety of biodegradable/compostable service ware (plates, cups, forks, etc.). The staff discovered that certain products, particularly those that are potato starch-based, do not break down quickly enough to be used with the composting system. PLA (polylactic acid) service ware has been a better choice.

Composting Operations

During the academic year, Ohio University processes about between 100 and 120 tons/month of food waste and bulking agent. For example, from January 2017 to April 2017, food waste tonnages ranged between 65 and almost 80 tons/month.

Wood chips, and a small amount of manure from a nearby horse farm, are used as bulking agents for composting the food waste. Food waste is mixed with the wood chips, which come primarily from landscaping operations, in a 40:60 ratio. They are measured out using the 65-gallon carts. All feedstocks are loaded into a mixer that discharges directly (after about 5 minutes of mixing) on to the first of a series of 14 stainless steel perforated trays that form the tunnel floor. The trays, each approximately 6-feet wide, 3-feet long, and 4-inches thick and weigh approximately 85 lbs, are pushed forward as a continuous unit by an external hydraulic ram.

Total retention time in the in-vessel composters is about 14 days. When the ram is moving an empty tray into the tunnel with fresh material, all trays within the tunnel are moving forward. Compost on the last tray is unloaded using a series of vertical breaker bars and an auger that discharges the compost onto a conveyor. The empty tray emerges from the tunnel. After an inspection, the trays are put on a wheeled dolly and pushed to the front of the composter where they are placed in a tray holder for insertion.

The 14-day composting process is divided into two “zones;” zone one is the active composting stage and zone two is called the “drying” stage (Figure 1). In between the two zones, a set of spinners located above the trays invert, homogenize, agitate and stack the material into the second zone. Water can be added to reestablish desired moisture levels.

The 14-day composting process is divided into two “zones;” zone one is the active composting stage and zone two is called the “drying” stage (Figure 1). In between the two zones, a set of spinners located above the trays invert, homogenize, agitate and stack the material into the second zone. Water can be added to reestablish desired moisture levels.

The tunnel is equipped with a series of probes that monitor temperatures. These temperatures, in relation to control panel set points, are used to operate air supply fans. The temperature set point in the first composting zone is typically between 136°F (58°C) and 140°F (60°C) for greater than three days to ensure pathogen reduction. A set point between 126°F (52°C) and 129°F (54°C) is used in the second zone to maximize conversion of putrescible materials. Any moisture that drains out of the composting material flows into the plenums that run along the base of the tunnel and from the plenums to sump boxes through pipes located at the sides of the tunnel. Leachate is pumped back onto the composting materials from the sump boxes, but a portion is released to the on-site septic system when the overall water balance is positive inside the machine.

Once discharged, the compost cures for at least 90 days. The windrows are turned regularly to crate a more homogeneous compost. During 2016, the system produced 429 cubic yards of compost, which is used as soil amendment by the campus grounds crew.

Overall, contamination of the incoming food waste stream has been minimal. Staff pulls out any contaminants — plastics, glass, etc. — when the organic waste is dumped into the mixing bin to be combined with wood chips, and again at the windrow stage. Anything missed is screened out at the finished product stage.

Dan Emerson is a contributing writer to BioCycle.