BioCycle December 2010, Vol. 51, No. 12, p. 22

BioCycle December 2010, Vol. 51, No. 12, p. 22

Seattle Mariners elevate organics recycling to new heights at a sports venue while boosting the organization’s bottom line.

Dan Sullivan

FOR the Seattle Mariners, conserving energy and recycling the huge waste stream generated during home games at Safeco Field are not only in line with the club’s environmental ethos. These practices simply make good business sense. For the past three years, shifting the behavior of employees and fans has gone hand in glove with modest maintenance infrastructure investments, leading to a 17 percent reduction in electricity use, shrinking the natural gas bill by 44 percent and adding up to more than $1 million in savings.

Since the first pitch flew off the mound in the Mariners’ then brand-new stadium on July 15, 1999, the bench has included an aggressive recycling program. Waste diversion really found its stride beginning in 2006, when now Vice President of Ballpark Operations Scott Jenkins – who holds a bachelor’s degree in construction administration- joined the club mid-year after overseeing the opening of the Philadelphia Eagles Stadium (Lincoln Financial Field), a facility that recently announced its own ambitious plans to go green.

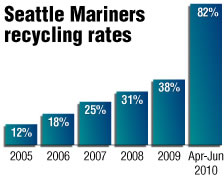

“In 2005, [the Mariners] were diverting 12 percent of the waste stream,” Jenkins told BioCycle. “I knew there were opportunities to do better than that. We did a few trash audits and quickly realized that organics was going to be a big part of it.” With capturing food waste for composting now part of the mix, the diversion rate climbed to 18 percent in 2006, 25 percent in 2007, 31 percent in 2008 and 38 percent in 2009.

The club had been progressively replacing nonrecyclables with compostable serviceware, says Jenkins, and diversion efforts were beginning to plateau. What helped the organization make the next big jump was basically a matter of perspective. Compost bins replaced garbage cans – 500 of them – around the stadium. “We basically flipped the switch and said ‘instead of defaulting to garbage, we’re going to default to compost.'”

The Mariners effectively shifted organics recycling from the back of the house to the front of the house, Jenkins explains, so that the time and energy spent on collecting garbage and sorting out the organics last year was channeled into composting this year. “There is huge opportunity – if you can manage the supply chain – to increase compost and decrease garbage,” he says.

Toward that end, the Mariners worked closely with strategic partners such as their concessionaire, Centerplate, Cedar Grove Composting and serviceware suppliers like Pak-Sher to convert their service items to compostable products. This has led to an overall $70,000 reduction in waste disposal costs and a recycling rate, measured during the first two months of the 2010 season, at 82 percent.

EDUCATING FANS

In 2010, there were basically two waste streams: commingled recyclables and compostables. While there has been some success with signage, fans are still on a learning curve. In many regards, Jenkins explains, it’s easier to compost by controlling the waste stream than it is to change behavior. “We’re striving for zero waste, and we had 17 zero waste stations around the ballpark,” he says. These stations included separate and clearly marked receptacles for compostables, bottles and cans (commingled recyclables) and garbage and were in fact the only places in the stadium where any actual garbage cans could be found. Above each station, pictures of the actual products clearly indicated which products went where.

But their efficacy was far from perfect. “If you take the lid off one of them, 80 to 85 percent of what’s in there belongs in the other two containers,” Jenkins says. Most of that – with the main exception being what fans bring in from outside the park – is recyclable. Still, most fans want to do the right thing, he adds, and Seattle offers the perfect backdrop for a green stadium. As one fan featured in a promotional video touting the Mariners’ composting efforts put it: “My mother’s favorite joke was about when the Mariners played the Yankees and they said the Yankees fans threw garbage on the field; the Mariners fans ran out and sorted it for recycling.”

Educating fans also includes press releases to local media, an annual Earth Day event and spotlighting of the Mariners’ recycling policy on the big LED screen throughout each game. The Mariners’ official recycling mascot, Captain Plastic, is featured on signage throughout the stadium and can be found wandering the corridors of the stadium before and during games making overtures to fans – especially young ones, who it is hoped will then relay the message to their parents and older siblings – to “Join the Green Team.”

“We’ve got 2,000 employees, 45,000 fans, and a stadium setting is kind of a party atmosphere,” says Jenkins. “In that type of environment it can be difficult to recycle. It’s the lesser of two evils to sort the garbage out of compost than to sort the compost out of the garbage. We also host a number of private functions including business meetings and social events at Safeco Field venue. We maintain our zero waste philosophy for these events as well.” All the collected compostables go to Cedar Grove Composting, which also serves as the official composter for City of Seattle residents and businesses.

USING TESTED AND APPROVED PRODUCTS

In July 2010, the city made it mandatory that all restaurants’ disposable items be either recyclable or compostable. “They’ve got to be able to be processed by Cedar Grove in the commercial process,” Jenkins explains. “Things have to be tested and deemed compostable by Cedar Grove.”

Part and parcel of developing one of the most comprehensive commercial and residential composting programs in the nation, Cedar Grove made the decision to pioneer compostable product testing and approvals. In 2003, just four products were accepted for commercial composting at the facility. That climbed to 400 tested and approved compostable products in 2009 and to more than 700 in 2010. With a desire to take the guesswork out of properly sorting the compostable waste stream, Cedar Grove partnered with various product manufacturers to develop a compostable products identification system using its logo and the color brown. Safeco Field and Mariners home games became the first proving ground for cobranded compostable serviceware. Cedar Grove also worked closely with the Mariners kitchen staff to guide them toward approved products. The Mariners close the loop by purchasing finished compost from Cedar Grove for use in planters and for other landscaping projects.

“We started a commercial collection program with our own trucks and our own equipment in around 2005,” says Stephan Banchero, general manager of the collection division of Cedar Grove Recycling. “The Mariners were one of the first big businesses to come on board with back-of-the-house preconsumer food waste.” Shifting that effort to the front of the house required some forethought, he adds. “We went through every product they generate – Scott [Jenkins] myself and food services to ensure that everything coming out of the stadium is either compostable or recyclable. Basically, everything that’s purchased through the stadium we can manage.”

The Mariners have been a key partner in the evolution of Cedar Grove’s commercial organics recycling program, Banchero says. While the Cedar Grove logo and brown stripe certainly make it easier to identify serviceware as “compostable” from beginning of life to end of life, he adds, the company does not require its commercial accounts to use them but does hold clients – and their haulers – accountable for making sure they use only tested and approved products in their compost waste stream. “[The commercial generators] are adding a service that is not mandatory in this area, so if a waste hauler is setting up service with a business, we expect them to be making sure their products are compostable.”

What is mandatory in Seattle is residential recycling of yard and food waste, and this is where Cedar Grove requires use of its logo on any compostable serviceware in the compost stream, with the exception of pizza boxes. “Residential composting is a different beast,” explains Banchero, “particularly when you are talking about servicing hundreds of thousands of homes.”

“Cedar Grove does not make or manufacture these [compostable] products, and we’re willing to accept any items that we can test and prove compostable. Our main goal is making clean compost – not putting a mangled fork in somebody’s backyard.”

Much of Cedar Grove’s success in Seattle is built around public awareness, says Banchero, and in that regard the Mariners play another key role. “Scott from day one said ‘this is not only about how to benefit the Mariners but it’s about people.’ The Mariners have been able to touch their fan base and hopefully educate them so they can take the knowledge home and to the workplace, seeing that composting actually works and why it’s important.”

Jenkins adds that the 8 to 10 percent [of noncompostables] going into the compost stream can be fixed by “managing what we buy” and predicts that as the compostable packaging industry evolves and becomes more competitive, performance will continue to improve even as the price of these products comes down. Fans bringing in items from outside the ballpark coupled with the fact that certain traditional baseball fare – such as chips and licorice rope – doesn’t come in compostable packaging are two reasons why actual “zero” waste might be a lofty goal, he says, but the Mariners will continue to strive to set an example for the rest of the league and may even take the lead in developing a “green professional sports teams” consortium.

“Every concession stand has point-of-sale signage at the register explaining that we’ve switched to compostable serviceware and that it’s not garbage any more,” Jenkins says. “An arrow goes from these products to a compost container. You get educated when you’re standing there waiting for your food. We utilize the same artwork that the City of Seattle uses for its three streams – compost, commingled and garbage streams.”

One ongoing challenge in that regard is that a large percentage of Safeco visitors are out-of-towners who may not be familiar with Cedar Grove’s trademark logo and brown stripe. “We aren’t going to ever get to the point that everybody gets this and knows it, so we have to make it as simple as possible,” concludes Jenkins. “We’re managing the supply side with compostable serviceware, PET and metal recyclables. We need to get better at public awareness and having people continue to act on it.”

December 22, 2010 | General