Dan Sullivan and Nora Goldstein

AS founder and Executive Director of Earth Economics, a nonprofit based in Tacoma, Washington, economist David Batker has completed more than a dozen studies that have changed economic policy related to ecosystem services internationally, regionally and locally. Batker earned his graduate training in economics under Herman Daly, one of the world’s foremost ecological economists, and has worked in ecosystem service valuation, trade and international finance for two decades. Earth Economics implements solutions such as helping to improve the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ Principles and Guidelines to include the value of wetlands for storm protection in Benefit-Cost Analysis nationally and specifically in Louisiana. Batker is also assisting the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to include ecosystem service values in that agency’s Benefit-Cost Analysis tools.

AS founder and Executive Director of Earth Economics, a nonprofit based in Tacoma, Washington, economist David Batker has completed more than a dozen studies that have changed economic policy related to ecosystem services internationally, regionally and locally. Batker earned his graduate training in economics under Herman Daly, one of the world’s foremost ecological economists, and has worked in ecosystem service valuation, trade and international finance for two decades. Earth Economics implements solutions such as helping to improve the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ Principles and Guidelines to include the value of wetlands for storm protection in Benefit-Cost Analysis nationally and specifically in Louisiana. Batker is also assisting the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to include ecosystem service values in that agency’s Benefit-Cost Analysis tools.

Batker was one of two presenters in a recent segment of a U.S. EPA-led “Consumption and the Environment Webinar Series.” After participating in the webinar, it became clear BioCycle shares a similar mission and sustainability goals as Batker and his organization. Earth Economics answers difficult questions about how we can move our 20th century economy currently built around consumerism into a sustainable model we can live with on a global scale. We interviewed Batker, who will speak at BioCycle’s 26th Annual West Coast Conference in Portland, Oregon, April 16-19, 2012. The following are highlights of our interview.

Here is the important point: The value of nature is no longer zero. And whether the low, high or an in between figure is used for policy, it provides an economic basis for dramatically changing the way humans interact with nature. The goods and services rendered include the provisioning, storage and filtration of drinking water; flood protection; pharmaceuticals; food; building materials; recreation; waste treatment; climate stability; habitat; biodiversity; nutrient cycling as well as cultural and aesthetic values. In addition, nature supplies sustainable jobs and the foundation for economic development.

Placing first priority on protecting natural systems for the services they provide defines Earth Economics. Based on traditional economic metrics, the recent Gulf Oil Spill was a boon to the economy, a success story. Every barrel of spilled oil generated a lot more GDP [gross domestic product] than if it had made it to your gas tank. Our national accounting system counts value of natural systems in the Gulf as zero. Only when it’s destroyed does it makes it on the balance sheet, and that’s backwards.

The national-scale problems of the Great Depression generated a national economy based principally on “built capital” (producing more stuff) that set the country on the road to economic recovery. In natural- versus built-capital terminology, we had plenty of salmon (natural capital), but we didn’t have enough boats and nets (built capital) to go catch them. Now that we’ve rolled along with the same system for 80 years, we find ourselves in a difficult place. We were successful in building stuff. We’ve got plenty of built capital, but are running out of natural capital. It’s become more scarce, so it’s more valuable. We have the boats and nets, but now we don’t have the salmon.

Built capital depends upon natural capital, which is in desperate need of our collective attention. This is where Earth Economics comes in. If we don’t look at natural capital as part of our overall economic infrastructure, then we probably won’t be investing in it. Going back to the salmon analogy, if we want more salmon then we have to restore habitat. The good news is that by restoring salmon habitat, we reap multiple benefits – ecosystem services that can and should be assigned a dollar value. Environmentalists feel uncomfortable with the idea of putting a dollar value on nature. But we’ve made the case that while we know nature’s value is intrinsic and immeasurable, we need to recognize nature for the services it provides. And sometimes that means instituting funding mechanisms to keep natural systems healthy. A human life is invaluable, but people still get paid for their work.

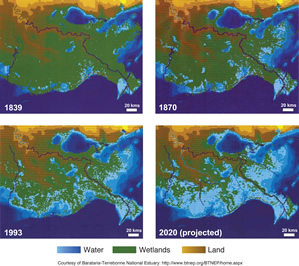

The reality in the Mississippi Delta, however, is that built capital for flood protection – levees – also incurs costs that include eroding and degrading wetlands by starving deltaic ecosystems of sediment and fresh water. Research has found that over 1.4 million acres of wetlands have been lost in Louisiana due to levees and canals for oil drilling and shipping. Carefully managed restoration of natural processes could rebuild the delta and the multiple benefits it provides.Levees, like virtually all built capital, depreciate over time. Wetlands, however, represent an appreciating investment that provides more service capacity year after year. Restoring wetlands on a large scale every year provides services that have nowhere to go but up. That levee is going to fall apart – it has a depreciation schedule. Our basic economic analysis is biased, because it doesn’t identify or measure value provided by natural capital. The choice is clear: Lose wetlands and have a retreating coastline, retreating economy and fewer jobs. Or restore wetlands, the economy and jobs. Levees are still needed, but are a waste without wetlands restoration. The real solution is built and natural capital.

We need to change the scale of how we make things happen, and we need new measurements and institutions. What is our water budget? How much water will it take to recharge our groundwater supply? What are we looking at with climate change in terms of rainfall and flooding potential? Envision local or regional institutions such as ‘Watershed Investment Districts’ that would take both the long and broad view in terms of prioritizing essential investment in ecosystem services.

We need to change the scale of how we make things happen, and we need new measurements and institutions. What is our water budget? How much water will it take to recharge our groundwater supply? What are we looking at with climate change in terms of rainfall and flooding potential? Envision local or regional institutions such as ‘Watershed Investment Districts’ that would take both the long and broad view in terms of prioritizing essential investment in ecosystem services.Earth Economics assisted Seattle Public Utilities with a project at the confluence of the Tolt and Snohomish rivers to restore salmon habitat. It was decided that a levee setback would help the salmon; it would also widen that confluence by about 50 to 60 acres. It was a $5 million project that restored salmon habitat, improved water quality and provided flood protection. The project helped demonstrate how multiple economic and environmental benefits can be gained in perpetuity within one project that improved built and natural capital.

Instead of 16 separate communities attempting to address their own individual problems while adding to each other’s collective woes, why not just use a more efficient approach for shared investment in ecosystem services. For example, storm water would be captured through enhancement of permeable surfaces rather than being dumped back into the river, thereby enhancing flood protection, recharging drinking water and providing a host of other services. There’s a marginal difference between investing in pipes to put storm water in the rivers and green infrastructure to recharge the aquifer. A flood district should be able to pay that difference because it reduces flooding.

An interagency Watershed Resources Inventory Area exists, but the cities identified the inability to actually fund these multiple benefit projects, particularly salmon restoration. We floated the idea to the cities and counties within the Green River Valley, as well as the Army Corps, of forming a Watershed Investment District (WID) that would have tax authority and the ability to save taxpayers far more money by ending “infrastructure conflict.” Alternately, within a WID framework there could be merging of some tax districts to coordinate better investments. While the latter idea was rejected for now, legislation forging a WID is drafted and we think it will pass. Everyone sees the payback to the their own budgets.

In today’s financial system, municipalities can float bonds to pay hundreds of millions of dollars for water filtration plants (that counts as an asset), but if they remove a road to reduce sedimentation in a watershed that filters the water to a higher quality and less cost than a filtration plant, it is a write-down on the asset sheet. The road counts, but watershed quality does not. Forests that provide such essential ecosystem services as safe drinking water are assessed solely for their timber and raw land value.

The history of Seattle’s drinking water source and how it became a successful watershed-based utility is an interesting case in point. At the turn of the 20th century, because of its unsanitary water supply, the city had cholera and typhoid outbreaks. The New York Times declared Seattle one of the most unhealthy cities in the U.S. In 1898, the whole downtown commercial district burnt down because they didn’t have enough water to put out the fires. Finally, the city said “enough is enough.” Citizens voted 97 percent in favor and bought the watershed above them. And they have the best water quality you can have.

National accounting standards should be changed to recognize the asset value of ecosystem services. We have a very good idea of the value of natural systems. It’s very easy to value watersheds just like you value water filtration plants. They should be reflected in the actual asset sheet, because they are providing value. Twentieth century accounting is biased toward what you spend money on to build and not the asset value of the natural systems. The way forward is to identify ecosystem services, to value them, take an appraisal approach, map the essential services and then set up a funding mechanism for the services they provide.

What’s the Economy for, Anyway

David Batker is founder and Executive Director of Earth Economics, a nonprofit whose mission is to apply new tools and principles toward meeting 21st century challenges of creating just and equitable communities, healthy ecosystems and sustainable economies. Batker’s new book, What’s the Economy for, Anyway? Why It’s Time to Stop Chasing Growth and Start Pursuing Happiness (Bloomsbury Press, 2011), coauthored by John de Graaf, will be in bookstores November 8 and available for ordering at Earth Economics’ website: www.eartheconomics.org.

What’s the Economy for, Anyway? offers an often humorous, always insightful perspective on why our 20th century economy based on built capital and conspicuous consumerism is broken – and what we can do to fix it (hint: natural ecosystems should be valued, and even monetized, for the essential services they provide). Chapter titles include: “The Grossest Domestic Product,” “Unhealthy at Any Cost,” “The Capacity Question” and “When (or How) Good Went Bad.”

“Our book is fun, accurate, easy to read and provides a breath of fresh air for thinking about what we really want out of an economy,” says Batker. “Is it ‘life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness,’ or borrow to the hilt and get your nose to the grindstone? From the banking, real estate, currency, employment debacle to happiness, we cover it with humor and facts.”